I grew up in the South, in central Florida, where I do not remember having seen a Confederate flag until 1978, when I was 14. That was the year I started high school, having moved a few years earlier from Sanford, a celery cutters’ town, to Orlando. My first memory of the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) will forever be associated with the overpowering smell of marijuana. It also calls to mind three other things: pickup trucks with high suspensions, the band “38 Special” and a vague fear that I would get my ass kicked.

I refer, of course, to the dreaded high school parking lot at lunchtime. The Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag — now called the Confederate flag — was the ever-present symbol of the “stoners.” At Boone High School, the stoners were working-class white southerners who hated preppies, surfers, the Christian kids and people like me — the nerds. Most people called them stoners, but some called them rednecks.

Were they racists? That is a complicated question. My elementary and middle school classes had been integrated, but at Boone High School, slightly more than one percent of the graduating class was visibly black. It was technically integrated, but practically segregated. As a mostly-white kid who had grown up with mostly-black kids, I found the near-absence of black students at Boone High to be profoundly unnerving. For one, I had to dress differently. No long shorts, no patterned silk shirts, no striped pants, no Converse high-tops and never, ever a leisure suit. These, I quickly learned, were “black” clothes and made me the butt of many jokes during my first six months at school.

Racism was wide and deep at Boone High, but it had little to do with flags. In my limited experience the most racist students were the preppies, followed by the Christians. The stoners, with their Confederate flags, had mostly grown up with black kids, and while they were hardly anti-racist radicals, I did not hear them tell racist jokes and I often saw them sharing bongs behind the bleachers with black kids. That said, I had no doubt at the time that the stoners would beat the hell out of me if I walked up to them at lunchtime. Nevertheless I associated that flag with their sense of themselves as outsiders — the kids who would not work at their dad’s office, the defense contractor down the road or at Disney World.

It was not until I went to college that I learned the ANV battle flag was a symbol of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and of opposition to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Perhaps the most important political figure to embrace it was George Wallace, the Alabama governor and eventual presidential candidate who famously said “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” in his inaugural address, and who barred the door of the University of Alabama to admitted black students. Having seen the flag used by Civil War re-enactors, Wallace embraced it as a symbol of opposition to integration. He claimed that federal laws integrating public transportation, universities and public schools violated “state rights,” using a tangled jumble of logic that is employed to this day. A hundred years before him, Southern planters who fought a war to preserve slavery demanded federal protection for slavery, not “state rights” — but that’s another story.

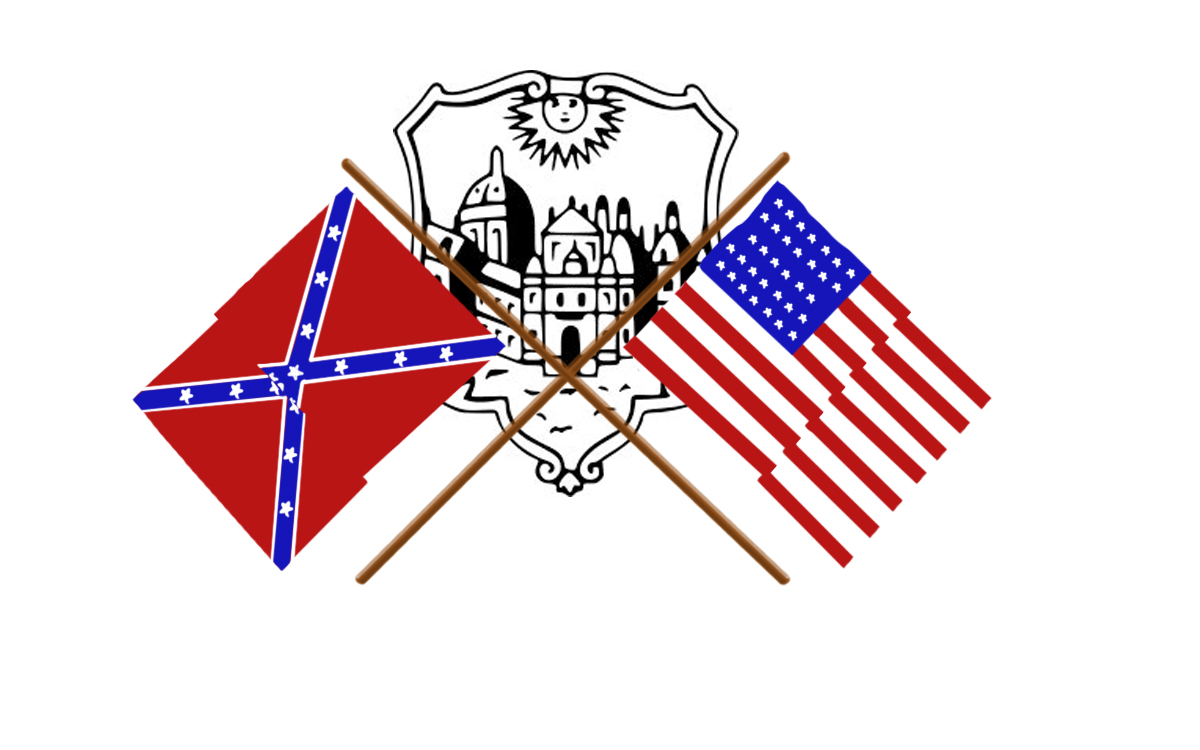

When I left Boone and went to college I learned that the Confederate battle flag was not just a symbol of white, working-class rebellion against the status quo, which was how I thought of it. It was not just a romantic symbol of a lost cause, like the Imperial Russian flag or the flag of the Habsburgs. It was also a symbol that was consciously used to terrify black people in the 1920s and the 1960s. Years later, I saw the phrase “heritage, not hate” on top of a Confederate flag. That was even more confusing, because for the stoners who flew it, the flag seemed to represent juvenile rebellion, working-class angst and an “up yours” attitude toward the school administration — not some storied Confederate heritage. I learned in college that the flag is also, very strongly, a symbol of hate. This is why we need to remove it.

Some people have argued that changing the mace and the concrete tablet on the Wren Building is an act of “political correctness.” Yet it was a kind of 1920s political correctness that led people to put the battle flag on the mace in the first place. It certainly wasn’t a reflection of the College’s actual history. The mace shows the flags under which the college operated. Faculty taught classes under a British flag before the Revolution, and they later taught under an American one after independence. But the College did not operate as a college between 1861 and 1865. Classes were not taught under the Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag, much less the actual flag of the Confederacy (a big white flag with the Southern Cross in the upper-left corner). In addition, the old concrete tablet only lists the names of the Confederate soldiers who fought. The same sort of political correctness in the early twentieth century led the College to list only the Confederate soldiers who fought between 1861 and 1865, and not its Union soldiers who also died fighting in the war.

Years later, the people that ensured that Boone High School and the College of William and Mary were mostly white but technically integrated did not wave any flags. They used school redistricting plans and admissions offices to do their work. Administrators and faculty played their part in making black students feel unwelcome. They did so in ways that are difficult to fully explain and sometimes difficult to see, such as the informal dress code I learned at Boone High. But to grow up and leave the horrors of the high school parking lot behind means recognizing that a symbol can appear innocuous at first but then troubling upon closer inspection. Learning to see a symbol with different eyes is our job as students and scholars and faculty. History is not just about celebrating or memorializing the past but also about learning from it, righting its wrongs, and making sure that the arc of the moral universe, as long as it is, bends toward justice.

Scott Nelson is a Leslie and Naomi Legum Professor of History at the College. He has written on the topic of the Southern Railway, as well as others, and has three published books with favorable reviews and national prizes.

Email Scott Nelson at srnels@wm.edu.

Prof. Nelson wrote: “Classes were not taught under the Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag, much less the actual flag of the Confederacy (a big white flag with the Southern Cross in the upper-left corner). In addition, the old concrete tablet only lists the names of the Confederate soldiers who fought.”

Are we straining at gnats now? That seems rather small and petty.

With one in three Southern households estimated to have lost a family member in the war and with an estimated 3:1 ratio of Confederate deaths to Union deaths, it is to be expected that the South’s pathway to healing focused on mourning its lost sons. Northerners, at least, had victory to console them.

And with those losses — and the fact Williamsburg was occupied by Union troops for much of the war — the depiction of the Confederate flag on the mace honors those young scholars who would have been there but for the deadly losses caused by the Northern invasion.

The anti-Confedrate kristallnacht is in full swing and there appears to be no stopping it. While I hope the madness stops soon, I’d like it to last long enough for the likes of Union Gens. Sherman and Sheridan — exterminators of the Plains Indians — to catch the eye of the iconoclasts. So many monuments yet to destroy.

Dear Mr or Ms “Lektrikwire,” I disagree because Nazis? That is not an acceptable argument. When you say 1 in 3 “southern households” but you mean 1 in 3 white Southern households you may have proved my point about people who don’t see privilege. PS: the Plains Indians were not exterminated. If you were an alum, I hope you were not a history major.

No, Southern households — 1860 Census households … father, mother, sons, daughters, slaves … households. Although the lost family member was invariably white — then, white privilege meant getting killed.

I don’t share your disappointment in Sherman’s and Sheridan’s inefficiency. Poor Sherman — on the eve of his death, was also bitterly disappointed, saying were it not for “civilian interference” his army would have “gotten rid of them all.”

God knows he tried.

Native Americans who stood in the way of the transcontinental railroad — their treaty rights notwithstanding — were massacred or forced onto impoverished reservations in what Sherman termed “the final solution of the Indian problem.”

“They did not,” he complained, “make allowance for the rapid growth of the white race … both races cannot use this country in common.”

To Pres. Grant he wrote, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children.” In a letter to his brother John, he said: “I suppose the Sioux must be exterminated …”

Black lives matter, Sioux lives not so much.

To his troops, he ordered, “During an assault, the soldiers cannot pause to distinguish between male and female, or even discriminate as to age. As long as resistance is made, death must be meted out …”

In another time and place, Sherman would have been hunting down Jews and forcing them into death camps. Come to think of it, Sherman, the anti-Semite, played an important role in General Order #11, expelling Jews during the war. All committed under the Stars & Stripes.

Sherman and Sheridan — that’s Phil Sheridan of “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” fame — were responsible for the near extinction of the American bison by 1882, its herds once numbering in the millions and the primary food source for the Plains Indians. Starvation was their goal — ecocide in the service of genocide.

For whatever it’s worth, Southerners, by contrast, did not starve their slaves. Just sayin’.

I’ll leave it to someone far smarter than me — you, perhaps — to explain how Union generals, who allegedly risked their lives to free Southern slaves, could turn around and callously murder Native Americans. Ditto for the Buffalo soldiers who used their newfound freedom to crush America’s native people.

Or do the grievances and sins and monuments and heritage of only certain groups count?

My experience growing up in a very small rural town at the lower end of Osceola county was a bit different. Confederate flags were not that common until desegregation and even then only were pulled out as a message, much like the crosses on occasional lawns. However, surprisingly, integration went fairly smoothly after the first years of elbowing little black kids getting on the school bus in ***ger Town at the edge of Saint Cloud. There’s no time to pinpoint when the elbows and spitting stopped, but the designation on the Chamber of Commerce wall map disappeared and it was not an issue if black people were in the town proper after dark at some point before 1971, when I hit high school. By 1972 my best friend was black and no one seemed to even care or at least didn’t voice any objections whereas previously having black friends made me the subject of the normal name calling.

What a “diverse” representation of viewpoints by The Flat Hat. Looks like we can forget about more reruns of the Dukes of Hazzard anytime soon. But to quote Daisy Duke: “I love that flag.” And the foregone conclusion of the Dr. Nelson is: Daisy Duke, pothead if not raving white supremacist and Klan member. Really, does anyone think a professor such as Dr. Nelson has any folk loyalties greater than his opportunistic malice against Southern white people? If Dr. Nelson is consistent with his logic, in addition to the Confederate flag he will add gay porn sites to his hall of infamy. After all, Dylann Roof’s Afro-American analogue, Vester Flanagan, was managing and promoting three or four of them shortly before he gunned down the reporter, videographer and publicist at Smith Mountain Lake last week. And what about the Obama badge Flanagan wore when covering political campaigns? What sinister symbolism and homicidal proclivities inhere in that? None I believe unless I evaluate by the same ideologically expedient logic Dr. Nelson uses to broad brush southern whites. But I’m really not surprised by Dr. Nelson’s methods. Hostile elites of his ilk have been gunning for us for years, and the Charleston Massacre gave them their breakout opportunity to throw the last remnant of our Southern heritage down the memory hole forever. I would caution, however, that when Dr. Nelson exploits seriously disturbed homicidal maniacs—who happen to wave a Confederate flag or Rainbow flag or a Koran– to symbolize whole groups of people he risk making himself as metaphorically delusional as they are. And if a semi-literate delinquent like Dylann Roof can dragoon a reputedly intelligent Professor of History into such an insidious folie a deux, as we see here, how susceptible are we students to expanding the insanity and allowing isolated

events to inform and stoke our own polarizing and recriminatory personal delusional system? Indeed, it is only a short step from Dr. Nelson’s “logic” to the paranoid processes of people like Vester Flanagan and a time when not just confederate flags but everyday words and phrases—“watermelon,” “swing by,” “in the field”–are politically incorrect, then finally trigger words for homicidal revenge.

I went to Oak Ridge when the writer was attending Boone. I remember seeing the flag on hats sold at Disney — but Disney back then didn’t have the problems with that sort of thing (they were still occasionally re-releasing Song of the South, for example).

The “black” school was Jones — although Oak Ridge was more than happy to use players such as Earl Carr and “Frog” Wilson to make the state playoffs. (Yes, he was called Frog because of his lips.) There was a “cheer” that the south county Oak Ridge stands would direct at the city Jones fans when the two schools played.

“Jones Hah, Jones Hah, WE FOR YOU!

Switchblade, razor blade, jackknife, too!

Jones Haaaaaaaahhhhhhh”

We were never enlightened… we were only pretending to be. It takes a lot of hard work to overcome that shit. But as to how people think that way now? Hell, you can’t slap a layer of paint on sewage and expect it to not be sewage.