(Note: Starred names have been changed to protect individuals’ privacy.)

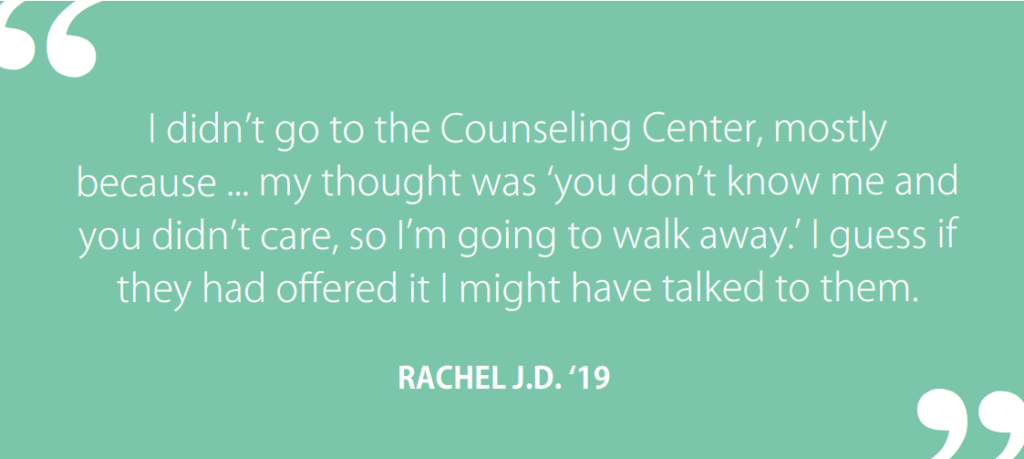

During her first year at the College of William and Mary’s Marshall-Wythe School of Law, Rachel* J.D. ’19 had frequent panic attacks that left her lying on the floor of her room, paralyzed by anxiety. She coped by holding “cry confession” sessions with a fellow law student, as well as confiding in her parents and getting involved with a local church, but never sought professional counseling.

Ryan Walkenhorst J.D. ’19 experienced mental health issues when she was prescribed an antibiotic with powerful side effects, including suicide ideation and depressive symptoms, earlier this year. The Student Health Center referred Walkenhorst to the Counseling Center, but after an initial consultation, she learned that her treatment needs fell outside of the center’s scope. The center offered to refer Walkenhorst to an outside provider, but because she was still on her parents’ insurance and did not want them to know she was seeking counseling, she declined.

Carina Sudarsky-Gleiser, interim director of the Counseling Center, said in an email that the center’s mental health services coordinator can connect students in similar situations with therapists who offer a sliding fee scale or free community resources.

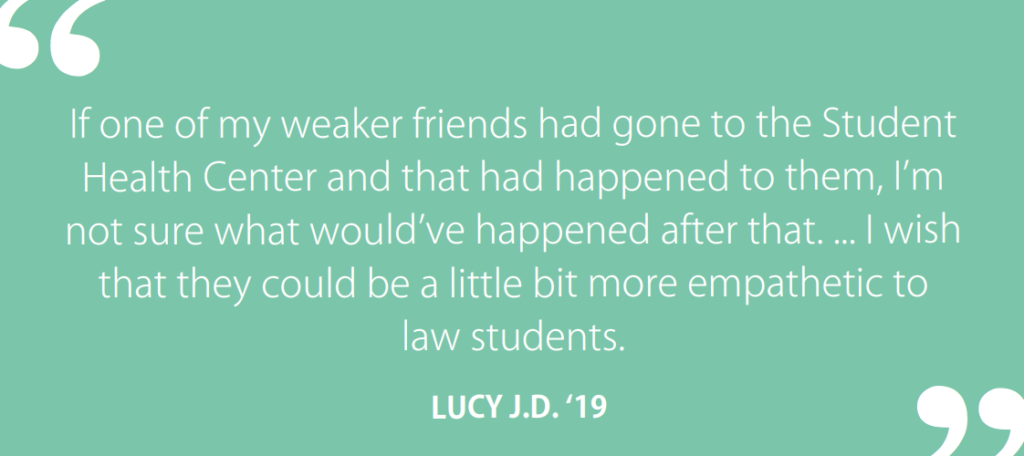

Lucy* J.D. ’19 said she never struggled with mental health prior to law school. Earlier this semester, however, self-doubt and constant pressure exacerbated the depressive thoughts that had cropped up during her first year in law school.

A professor advised Lucy to speak with a law school dean regarding her mental health, and the dean encouraged her to seek professional treatment. Lucy said she plans to visit the Counseling Center during the coming weeks.

According to multiple students at the College, the Darwinian, anxiety-inducing law school of popular imagination isn’t far from the truth: several sources described a small, close-knit yet cutthroat community — just over 600 students attend the College’s law school — where one’s classmates are perceived as the competition and professional treatment seems less accessible than alcohol, drugs and similarly unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Other students acknowledged the competitive nature of law school but said the College offers a welcoming, supportive environment.

It’s no secret that law students face constant academic, career and social stress — coupled with a high incidence of substance abuse and mental health issues. In 2014, a nationwide survey of 15 top law schools found that roughly a quarter to one-third of respondents reported frequent binge drinking, misuse of drugs and/or mental health challenges.

These issues are often compounded by unwillingness to seek professional support. Out of the 42 percent of survey respondents who indicated they had thought about finding help for mental health issues over the past year, only half had actually sought counseling. Discouraging factors included perceived threat to academic or job status, social stigma and potential impact on bar admission.

Two students at the College said these concerns are further intensified by the perception of law students as perennially stressed out individuals — a stereotype that both students claim led the Student Health Center to dismiss their symptoms of mental illness.

During the 2016-17 academic year, Rachel and Lucy visited the center for reasons unrelated to mental health. Last December, while Rachel was waiting for a prescription, she filled out the PHQ-2, a two-question screening tool that identifies individuals who may be at risk for depression.

The center asks all patients to fill out the PHQ-2, but students are free to decline. Respondents rate their interest/pleasure in doing things and feelings of depression or hopelessness over the past two weeks on a scale of zero (not at all) to three (nearly every day). A score of two or higher is considered “abnormal” and may warrant further treatment.

Rachel said she filled out the PHQ-2 honestly, reporting strong feelings of depression and hopelessness. When the nurse saw the high score, she allegedly asked Rachel what graduate program she was in.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I’m a law student,’” Rachel said. “And then she just took [the test] and ripped it off and said, ‘We don’t accept your data. We don’t accept your questionnaires because you skew our data, because you all put that.’”

Lucy had a similar encounter with the Student Health Center this March. She was about to depart for spring break and needed to pick up medication to treat a fever. Like Rachel, Lucy filled out the PHQ-2 and received a high score.

According to Lucy, when she identified herself as a law student, the nurse chuckled and said the center usually didn’t pay much attention to law students’ screenings. The nurse also told Lucy that the center didn’t keep these screenings because they skewed the data — the overall message, Lucy said, was that law students are and always will be stressed out due to the intrinsic pressures of law school.

Student Health Center Director Virginia D. Wells denied the allegations, saying, “[They are] categorically not true.”

Wells said the center does not keep an aggregate data pool similar to the one referenced in the allegations. She said that clinicians instead personally address abnormal test results with patients, perhaps by referring them to the Counseling Center or identifying responses as everyday stress rather than a diagnosable mental illness, before filing screenings in individual medical records.

All PHQ-2 results, however, are recorded for quality improvement purposes. Wells periodically reviews a list of results, which are coded as normal or abnormal, to ensure that every case has been properly addressed. If she sees an abnormal screening without a recorded follow-up, she intercedes. PHQ-2 results are not grouped beyond normal versus abnormal, as they are used to assess the Student Health Center as a healthcare provider rather than track the incidence of mental health issues amongst respondents.

Wells repeatedly dismissed the allegations, alternatively describing them as an exaggeration, an outlier of everybody else’s experiences and the equivalent of ripping up a medical record, which “would never happen.”

She said that law students are sensitive to issues surrounding mental health, particularly because of a question on the bar exam that asks respondents to disclose prior treatment for such issues, and may be reluctant to seek professional counseling or even fill out a screening tool such as the PHQ-2.

“We tell law students it’s OK, that seeking services has never kept them from taking the bar,” Wells said. “[They are] unduly paranoid.”

Wells declined to offer suggestions for law student-focused initiatives because she said the group is “not a unique population,” and its members are free to utilize the same resources available to all students at the College.

Both Lucy and Rachel said that by the end of their respective appointments, they had not received a referral to the Counseling Center or information regarding additional mental health resources.

Rachel did not seek professional counseling following her visit to the Student Health Center.

“I didn’t go to the Counseling Center,” Rachel said, “mostly because … my thought was ‘you don’t know me and you didn’t care, so I’m going to walk away.’ I guess if they had offered it I might have talked to them.”

Lucy said that if the Student Health Center had referred her to the Counseling Center, she would have made an appointment.

“I have friends who legitimately want to kill themselves or just want to die,” Lucy said. “And I mean, that’s not me in a big regard, although I have had those thoughts, but if one of my weaker friends had gone to the Student Health Center and that had happened to them, I’m not sure what would’ve happened after that. You know what I mean? I wish that they could be a little bit more empathetic to law students.”

Rachel, Lucy and Walkenhorst said mental health issues — and related law student stereotypes — are prevalent amongst their peers due to the high-pressure, competitive nature of law school.

“[The school] says, ‘Oh, these are your colleagues,’” Rachel said. “Then they explain how [grading works], and it’s all a competition. … It’s one of those things that if you let it get in your head, it’s not worth it, so I try to do things outside of the law school.”

At the College, grades are allocated according to a specified distribution curve (only 10 percent of students might earn an A, for example, while 20 percent earn an A-, 35 percent a B+, 20 percent a B and 15 percent a B- or lower). This practice is common amongst law schools, although institutions including Harvard University and Yale University have moved away from the curve, instead opting for pass-fail or alternative grading systems.

Rachel, Lucy and Walkenhorst all said the curve fosters an ultra-competitive environment. As Lucy explained, when students take an exam, their goal is to outperform the individual sitting next to them. Due to the comparative nature of curved graving, one student’s success comes at the cost of another’s relative failure.

According to Rachel, the curve discourages camaraderie amongst students, with individuals declining to share outlines for fear of boosting another’s performance or even hiding library books to prevent classmates from accessing them.

“If you do well, you can’t tell anybody about it because … that means somebody else around you didn’t do well,” Walkenhorst said. “Everyone talks about doing badly even if they haven’t. It’s just that competitive.”

Other students maintain that the College’s law community is generally supportive. Blake Willis J.D. ’18, president of the Student Bar Association, the law school’s governing body, said the school offers a welcoming, collegial environment, as opposed to the hardcore, cutthroat standard found at some institutions.

Callie Coker J.D. ’19 agreed with Willis, saying the College is less competitive than many schools. Still, she added that competition is an inherent aspect of law school, in large part because of the grading curve.

“For me, [what’s helped has] been finding friends who are supportive and aren’t openly competitive,” Coker said.

The College community addresses the pressures faced by law students in a variety of ways. During orientation, incoming students receive advice on how to combat substance abuse and mental health issues. Information regarding campus resources, including the Student Health Center and Counseling Center, is accessible online.

Both SBA and law school administrators send periodic emails reminding students of available support. Walkenhorst serves as the president of Lawyers Helping Lawyers, a student-run group that hosts events focused on topics such as mindfulness and imposter syndrome. Still, Walkenhorst, Coker, Lucy and Rachel said that more could be done to continue the conversation.

“I hear people make jokes, daily, either wishing they were dead or telling me that they literally sometimes think about how much easier it would be to not to be alive anymore,” Walkenhorst said. “It’s multiple people, multiple digits, and I don’t think the school realizes that. Or, if they do, they purposefully put their head in the sand about it.”

Lucy described classmates who cope with the help of alcohol, hookah, Adderall and hard drugs including cocaine and heroin. She said that professional treatment is there, but it doesn’t seem like the most readily accessible option. When a student tries to make an appointment at the Counseling Center but cannot secure an immediate timeslot, for example, Lucy said it’s easier to turn to the instant gratification of drugs and alcohol.

“[Mental health] is not something I’m constantly being told about,” Lucy said. “I’m constantly being told about employment, so I feel in a sense like my mental health is less important than grades and everything else.”

Coker also emphasized the need for ongoing discourse regarding mental health, saying that issues are discussed during orientation and exams but rarely mentioned outside of these periods.

She suggested several methods of continuing the conversation: holding workshops regarding substance abuse and mental health within the law profession, plus sessions specifically for job-seeking second year students, and perhaps reconsidering the widespread availability of alcohol at law school events.

SBA informally proposed another resource — a counseling space within the law school — during a discussion with administrators earlier this month. Willis said that he and other members of SBA had heard about similar centers at other schools and thought the idea was worth exploring at the College. According to Willis, the administration is looking into the issue and has not yet offered definitive feedback.

SBA Vice President Alyssa Kaiser J.D. ’19 added, however, that the discussion could be the start of positive changes.

“I think it’s an open conversation with the administration,” Kaiser said. “Luckily, they’ve been very receptive to having the conversation.”

[…] jobs you would never believe exist, sexual harassment in a small Scottish town, law students’ mental health, and grade inflation in Loudoun County; interviewed sources including a Holocaust survivor, Tlingit […]