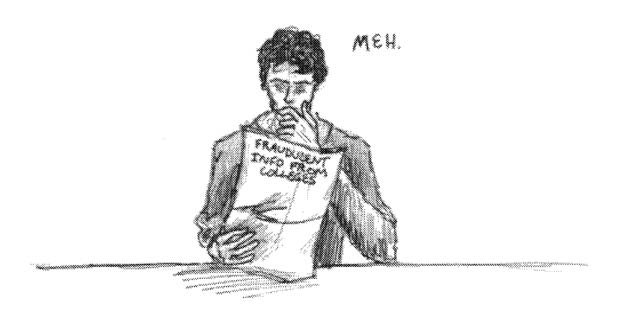

If you read the Washington Post headline, “Five colleges misreported data to U.S. News, raising concerns about rankings, reputation” Wednesday, do you remember your reaction? Was it shock? Revulsion? Disappointment? Perhaps the Internet and the 24-hour news cycle have made me into a jaded cynic, but my reaction was indifference. And at this point can you blame me? Ten-plus years of learning that my favorite baseball players were syringe-binging cheaters has made me numb to scandal. Shock was eliminated from my repertoire of emotions long ago, as was disappointment. Disappointment hinges on expectation and emotional attachment. Aside from the College of William and Mary I do not have much — if any — emotional attachment to universities. Further, with all of the scandals that we have witnessed in higher education, I have no delusions as to the muck that some colleges are covered in. Thus, I could not muster up any disappointment at learning that a few schools sent fraudulent information to U.S. News and that the subsequent college rankings might be slightly tainted.

Truth be told, the only disappointment that I felt when I read the Washington Post headline — and the subsequent story — was that I have become desensitized to indignity. However, just as I was beginning to think that I was nothing more than a hollowed out man of tin, I read an article about Illinois’s Augustana College.

Augustana recently published “The Augustana Story,” a report filled with the facts that prospective students might want to know but that most colleges do not share. The information on the report includes student outcomes, faculty teaching loads and where tuition revenue is going. Some of the data does not reflect particularly well on Augustana. For instance, Augustana’s graduation rate is higher for white students than for non-white students, and students’ average debt at graduation is increasing. Yet, all in all, Augustana deserves a tremendous amount of credit for its transparency.

Today, this type of transparency has become increasingly important. Sadly, in the court of public opinion it seems we have reached an age of guilty until proven innocent. We are living in a world where money and power motivate cheaters to cheat, and technology and resources enable them to stay a few steps ahead of investigators. It is no longer enough to abstain from taking performance-enhancing drugs. A clean athlete who is concerned about his image and the sanctity of his sport must also come out and expose the illicit undercurrent of his respective sport to the world. Honest politicians, who claim to oppose Citizens United, must indicate where all of their campaign contributions are coming from. And colleges, whose honor codes are meant to reflect and inspire a culture of honesty and integrity, must follow suit and create their own versions of “The Augustana Story.”

I am sure that if the College published a report similar to Augustana’s it would contain some ugly truths, but that is okay. We live in a generation that is numb to scandal, corruption and inefficient bureaucracy. Without Augustana-esque transparency, a tradition of honor is little more than an antiquated veneer of devout righteousness. The College’s bricks are red, not yellow. Our president might be Santa Claus, but he is certainly not a wizard. Nonetheless, a “College of William and Mary Story” unquestionably would be a noble step toward creating a larger culture of transparency that might just give a few tin students their hearts and their long lost innocence back.

Email Max Cea at mrcea@email.wm.edu.