“The more things change, the more they stay the same,” wheezes the twenty-something-year-old Infinity Gold stereo. The antenna, that chrome-covered symbol of hand-me-down adolescent freedom, translates invisible information into the voice of Kenny Chesney.

The Jeep, a paradox of antiquation without irrelevance, almost sighs as night clouds begin to spatter their burden on its windshield. Wipers slosh the rain into an impressionist painting of night and the occasional nebula of a traffic light. The prodigal daughter sits in the driveway leaning against the steering wheel and inhaling its mileage-smooth leather. Beads of water, in their heaviness, trundle onto the hood before she retracts the antenna and ends the generational nostalgia of fuzzy radio waves.

After the benevolent attack of squirming, fluffy shepherds, the parents ask about the trip down 340 to the east side of the county and the barely-hamlet of Dooms. Dooms looks exactly like the name implies. Then the father, with a head of silvery grey hair and steely blue eyes that discern what is to most only minutiae, comments that the Purple Cow had stood in Dooms since his youth.

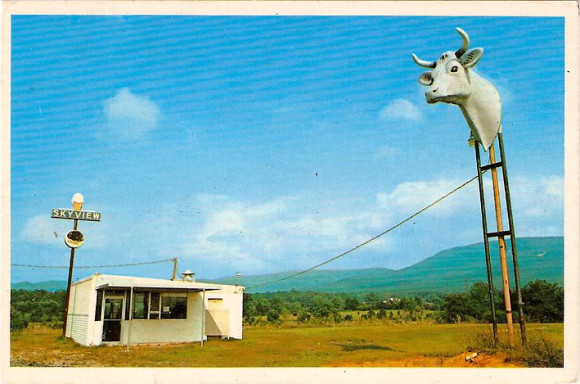

The Purple Cow had just reopened after decades of vacancy, but almost anyone who drove by, if they had a reason to drive through that part of the county at all, would recognize it from its former glory days. A statue of a head that continues into the smoothly muscled neck of a lavender dairy cow stares down a gravel driveway and parking lot with nonchalant awareness. A small, boxy, nondescript roadside building gives an impression of the 1960s, and a cartoon-ad-like sign, rusted from many springs of rain and summer thunderstorms, crowns it with the picture of a classically American summer ice cream cone and the word “Skyview.” No, it couldn’t have changed since its conception. Nothing changes at the base of the mountains, the grounding of their stolidity. Cars with big engines — forget Priuses — and young people with nothing better to do after 7:00 in the evening flock to the picnic tables and, with a change of dress, could have stepped out from a scene in a postcard found in a grandmother’s attic.

Behind the L-shaped counter inside the squatty structure, accents on the walls match the gargantuan face of the bovine outside. Pepto-Bismol pink and caterpillar green swirls of chalk declare the day’s ice cream flavors and the prices for whatever produce has been plucked from a field that morning. The impersonal pace of the outside world hasn’t extended its fingers this far into Virginia, and the two women — one at the register, the other handing out malleable globs of sweetened, churned cream — reflect the feeling of the rest of the establishment. Both of their eyes are as warmly luminous as the colors around me. They hand out mountainous bowl after scepter-like cone with maternal warnings against ill-fated melting.

Indeed, the picnic table shaded by an umbrella against the disappearing sun wore a couture of crinkled paper napkins after ice cream had been licked from spoons, bowls and fingers and the unfortunate solid-become-liquid at the bottom of the cone had been thrown shot-like to the back of throats. After semi-ridiculous, semi-serious debate had subsided about the merits of banana ice cream — a banana’s natural adiposity marries perfectly the pale fat of ice cream and the author will fully endorse it over raspberry at any given time — talk turned inevitably toward the impending return to college. This was the last visit of the summer where each of us would be together. This was, for all intents and purposes, the last summer which all would pass in the same corner of the world.

The parting mood jars against the jubilantly-hued cow. Our summers had abounded with familiarity thus far: working part time jobs, rattling around a county that we called home, languishing under the clearest skies for hours covered in bug spray and sunscreen and eating unhealthy amounts of churned cream whenever possible. Soon we were to scatter across the state and then farther into yet unknown and unvisited places. Each would now discover a new circle of friends with whom to spend future summers, and we seemed to watch each other part in a dream.

Somehow, the opaque, painted eyes of the cow and the seasoned swing of an oft-traveled road knew intimately this feeling; their knowing granted solace again as they had for the decades since the dawn of the automobile, the construction of the roadside attraction and the heightened disquiet at the coming of age.