I’ve carried around a picture of Thomas Jefferson and of Monticello in my wallet for nearly a decade now — a souvenir from a middle school trip to the president’s home which I’ve never parted with. This isn’t an isolated bit of Jefferson fandom in my life. I used a copy of the Jefferson Bible in lieu of an actual Bible while participating in one of my fraternity’s membership rituals, participated in a public debate where I defended the Jefferson statue’s existence on the College of William and Mary’s campus and am a student of the College’s Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy.

In short, I’m probably the last person certain reactionary alumni of the College and others would imagine when contemplating the band of politically correct leftist radical yahoos who think it’s okay to smear paint on a statue to make a larger historical point.

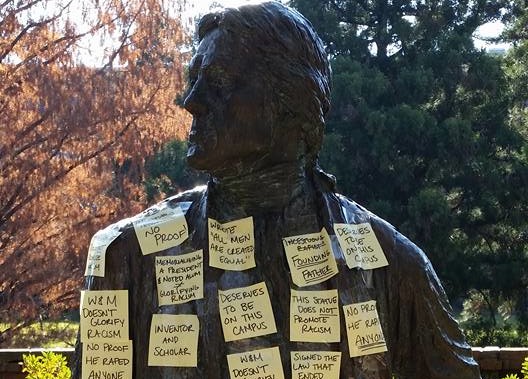

By contrast, this piece is to defend the justified and reasonable actions by the individual or individuals who participated in the defacing of the statue this past week.

This piece isn’t to defend Mr. Jefferson’s legacy — though I am personally comfortable in continued positive historical remembrance of the man for many reasons. Mr. Jefferson’s legacy has been and will continued to be defended by many. By contrast, this piece is to defend the justified and reasonable actions by the individual or individuals who participated in the defacing of the statue this past week.

The direct action carried out has served to start a meaningful discussion. While, like many of our generation’s arguments occurring in the public space, it has mostly occurred on Facebook, it has also occurred in our halls, in our classrooms and in our everyday interactions. This discussion is incredibly important.

The way we choose to remember Mr. Jefferson should not be dictated by authoritative power structures or by a sheepish devotion to the status quo, but by the actual feelings, thoughts and emotions of our community.

Historical remembrance requires dialogue and communal reflection. The way we choose to remember Mr. Jefferson should not be dictated by authoritative power structures or by a sheepish devotion to the status quo, but by the actual feelings, thoughts and emotions of our community.William and Mary has historically chosen to embrace a remembrance of Mr. Jefferson, which excludes slavery. Perhaps this is a justifiable move, if we decide that the construction of Mr. Jefferson is not an accurate reflection of a real person but of a useful positive figure in the way that many of history’s large personalities have had negative aspects of their lives overlooked when disproportionately positive contributions to society exist.

Because the most telling reaction to the defacing of the statue was not the rather demonstrably false argument that the protest is meaningless or ineffective (the intensity of some arguing against it demonstrates that it is clearly effective in starting a discussion), nor the weak argument that the effort it would take facilities workers to hose off the statue was a moral crime. It was the visceral emotion of hatred of many who opposed it.

To some, positive historical remembrance to Thomas Jefferson is a foundational value — one that is immutable and cannot be challenged.

To some, positive historical remembrance to Thomas Jefferson is a foundational value — one that is immutable and cannot be challenged. Any action, whether in paint or sticky notes or protest, is inherently threatening to this ideal. Ironically, though, that conception of the infallibility of entrenched patterns of interpretation stands in nearly direct opposition to the values of liberalism and democracy that Jefferson praises our society for in the first place.

One commentator on the Jefferson statue incident remarked that “this behavior is disappointing.” I agree that some pretend that washable paint is more dangerous than a discussion regarding how we approach the past exhibit behavior, that is disappointing.

Email Venu Katta at vrkatta@email.wm.edu