Friday, Feb. 9 the College of William and Mary’s English department hosted a talk given by Henry Jenkins entitled “Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination.”

Jenkins is a professor of communication, journalism, cinematic arts and education at the University of Southern California. Prior to that, he was the director of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s comparative media studies program. In his talk, Jenkins discussed his work on the ways in which popular culture is utilized in political activism.

English and American studies professor Elizabeth Losh introduced Jenkins. She spoke about her experience teaching Jenkins’ book “Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide” in her classes and said Jenkins’ visit and message tied into the College’s history and efforts to promote leadership and civic involvement. According to Losh, Jenkins’ work is particularly poignant in the current political climate in the United States.

“In a time of political division and disaffection, Jenkins also has much to say about the civic imagination and the promise offered by participatory world-building as a method to use stories about science fiction, superheroes or magic to effect more engagement in civil society in the real world for people in all walks of life,” Losh said. “… Jenkins’s message crosses many generational lines to advocate for empathy, care, empowerment and ethics with case studies from around the globe.”

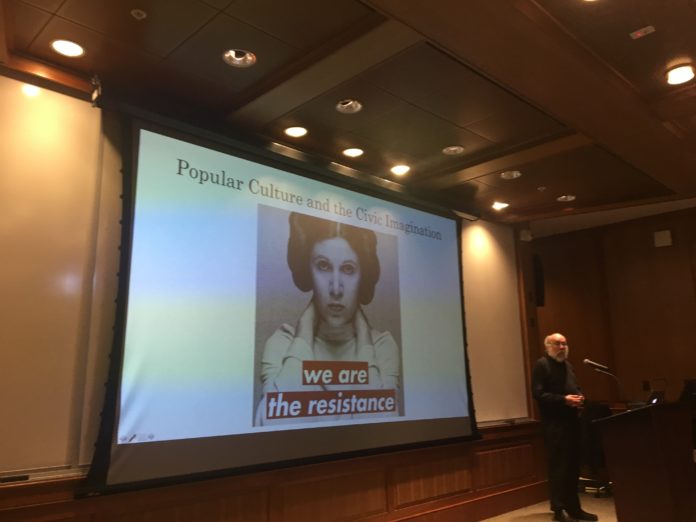

When Jenkins took the floor, he opened his talk with a PowerPoint slide featuring an image of Princess Leia from Star Wars and the slogan “We are the resistance.” Throughout the presentation, he returned to images featuring pop culture icons and political slogans that have been seen in recent political protests.

Jenkins noted the way that “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda has used the fame he has gained from the musical to speak out about political issues and current events. Miranda has spoken out about gun violence after the 2016 Orlando shooting, about disaster-relief in Puerto Rico and has been a prominent voice in the immigrant rights movement.

“Hamilton” is not the only work of pop culture being used to further the immigrant rights movement. Superman has also become a feature of the movement.

“If there was an illegal alien, Kal-El from the planet Krypton might be a good poster child,” Jenkins said. “Kal-El’s parents sent him away from a dying world in search of a better place to live a better life someplace else. He crosses the border in the middle of the night, lands in a cornfield in Kansas, is adopted by an Anglo couple that teach him to hide who he is and where he came from. Nevertheless, he goes out and fights for true justice and the American way of life. … All of that adds up to a really powerful story that rethinks the Dreamers and the experience of undocumented youth in America.”

According to Jenkins, this connection of Superman to current immigration activism is especially interesting because immigrants created the character in the early 20th century.

“The fascinating thing is that Superman has been an immigrant story all along,” Jenkins said. “In the late 1930s Superman was created by Eastern European immigrants to explain their experience of immigration and their experience of finding a new world. These two immigrant groups have connected across an 80-year period of time to revitalize this myth and use it as a political tool.”

Jenkins said that in using popular culture in activism, there are often times when the element of pop culture is used in a different context than what it is referencing, but that the pop culture elements are built upon to become something greater when they are utilized for political activism.

“I love the fact that we were watching a generation that was supporting Bernie Sanders and supporting the founder of Wall Street at the same time,” Jenkins said. “It’s kind of a weird paradox of listening to ‘Hamilton’ on your earphones while you’re marching in support of Bernie Sanders, but in fact, the vision of ‘Hamilton’ that Lin-Manuel Miranda offers is a vision of an alternative history, an alternative conception of the United States and one that was framed as a diverse America.”

According to Jenkins, young people are drawn to activism that features popular culture because it is a shared language that people understand. He compared the use of pop culture in modern activism to Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of Biblical references in his activism. Jenkins said the communities King spoke to had a deep shared knowledge of the story of Moses the way that young activists today may have a deep and shared knowledge of the “Harry Potter” book series.

“What we’re finding is for more and more young people in the US and around the world, the language they share and the language they use for the civic imagination come from popular culture,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins spoke about an organization called the Harry Potter Alliance, an organization that engages in activism surrounding human rights and literacy, rooting its activism in the themes of the “Harry Potter” series. In 2014, the organization led an activism project to persuade Warner Bros. into using Fair Trade chocolate for Harry Potter-branded candy.

Jenkins pointed to this instance and to photos he showed depicting protestors using the three-finger salute from the “Hunger Games” series as examples of the ways in which pop culture fandom can inform activism.

“Many people avoid talking about politics in social gatherings because it’s become so divisive … but fandom often provides explicit spaces to come together and talk about social change, which is historically what activism has done,” Jenkins said.

In the question-and-answer portion of the talk, students, professors and community members in attendance asked Jenkins to elaborate on some of the topics he touched on in his presentation. American studies graduate student Leah Kuragano asked Jenkins about the ways in which groups use popular culture in activism across the political spectrum.

“You’ve talked about some of the instances in which the center-left has used pop culture to imagine a utopic future,” Kuragano said. “Do you also see in that framework the development of utopic futures through pop culture on the far-right, the center-right and the far-left?”

According to Jenkins, groups are engaging in activism that utilizes pop culture all across the spectrum, but academic scholarship tends to skew left.

“It’s been easier to get academics to write about the cool stories of what the left is doing than to get people to really dig deep in the muck pit of the alt-right,” Jenkins said.

In Jenkins’ view, the United States is going through a tumultuous political time, but he believes the country is heading for an upswing, and pop culture-laden activism will help move that tide forward.

“I often have my writing accused of being too celebratory, and I’ve sort of decided in my older age to own that and just say, ‘yes, I’m excited to tell you about things that are happening,’” Jenkins said. “There are plenty of things that I’m observing in the world that make me think we may be hitting rock bottom and then finding our way out again.”