*NOTE: This is the third segment in a series on former professor David Dessler. It focuses on the College administration’s handling of his case based on stated procedures regarding faculty leave and termination. Next week, The Flat Hat will explore how Dessler’s story relates to the culture surrounding mental health at the College. Visit SoundCloud to hear the podcast version of this series.

![]()

By Meilan Solly

According to court documents, correspondence and interviews, a key point of contention between the College of William and Mary and former government professor David Dessler is the timeline surrounding his case: While the College states that Dessler remained a tenured faculty member until his June 18, 2017, resignation, he says the Aug. 9, 2016, listing of his employee status as “inactive” was tantamount to wrongful termination.

College spokesperson Suzanne Seurattan said employees on short-term medical leave have several options upon reaching the end of a leave period: apply for long-term disability, which may require documentation from a health professional; retire, if one has the service credit required; provide assurance of one’s readiness to return to work; or take no action.

Opting for the last path, Seurattan said, results in the employee’s status changing from active to inactive.

“An individual cannot be considered an active employee if he or she is not working or using accrued paid leave,” she wrote in an email. “The unusual circumstance of an employee not taking any of these actions would put an employee in inactive status.”

The College’s Faculty Handbook, which outlines faculty rights, responsibilities and procedural information, does not mention inactive employee status. Based on the definition provided by Seurattan, however, inactive employees remain on the College’s staff and are entitled to return to work, apply for disability or retire. They are not eligible for pay and benefits.

Within two weeks of Dessler’s listing as an inactive employee, his pay, insurance benefits and College email access were cut off. Still, according to the College’s stated parameters, he remained a tenured faculty member.

Sept. 8, 2016, former Provost P. Geoffrey Feiss, Chancellor Professor of English Emeritus Terry Meyers and Chancellor Professor of Sociology Kate Slevin submitted a letter of support for Dessler to the provost and Faculty Assembly. In it, they wrote that the College had “effectively fired a senior member of the Faculty in violation of the letter and spirit of the Faculty Handbook.” To rectify this alleged violation, the emeritus faculty recommended that Dessler be immediately reinstated to his salaried position and given the due process rights outlined in the handbook.

“Here was a case of a faculty member who, whatever the originating causes … was in effect fired,” Meyers said. “[He was] removed from his position with loss of salary and benefits and told nevertheless that he still had a tenured status, a standing that I’ve never heard of in the academic world.”

In response to the emeritus faculty note, Provost Michael Halleran denied all allegations.

Dessler] has not been terminated, but, without an indication of an ability to return to work and with the exhaustion of his paid medical leave, he was removed from the payroll as there is no other reasonable status for him as a tenured faculty member,” Halleran wrote in a Sept. 13, 2016, memo.

The distinction between an “inactive” status and termination is a complicated aspect of Dessler’s story, and it raises several additional questions: Why did Dessler — who, in a July 26, 2016, letter told Chief Human Resources Officer John Poma that he had sought medical care and intended to resume full-time teaching during the fall 2016 semester — decline to provide documentation that would facilitate his return to teaching? If Dessler had, as he and the emeritus faculty members say, been effectively terminated, what procedural guidelines were ignored?

According to page 25 of the Faculty Handbook, the termination of a tenured faculty member can only be effected for adequate cause, including incompetence, misconduct and medical reasons. Page 75 further states that administrative officers who find evidence that a faculty member is unable to perform his or her essential duties must discuss the problem with the employee and attempt to reach a satisfactory solution. If this fails, the provost submits a report to the Procedural Review Committee, which initiates an informal investigation. If the committee is also unable to reach a solution, the provost initiates a formal investigation overseen by the Faculty Hearing Committee.

“The burden of proof that the faculty member is no longer able to perform the essential duties of the position,” the handbook states, “even with reasonable accommodation, rests with the College and shall be satisfied only by clear and convincing evidence in the record considered as a whole.”

Because Dessler was classified as inactive, the College repeatedly told him he was ineligible for a hearing. Documents filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, however, show that following Dessler’s listing as inactive, the College “initiated proceedings under the Faculty Handbook to terminate [his] appointment as a tenured professor for medical reasons and misconduct.” Dessler subsequently resigned from his position June 18, 2017.

According to court documents, Dessler decided to resign to avoid continued harassment by the College.

According to court documents, Dessler decided to resign to avoid continued harassment by the College.

After enduring five arrests and 77 days in jail, Dessler told The Flat Hat he was tired of living in constant fear.

“I thought I might be arrested again,” Dessler said. “I couldn’t figure out how to predict when I would get arrested, because I wasn’t breaking any laws, just [making] people mad.”

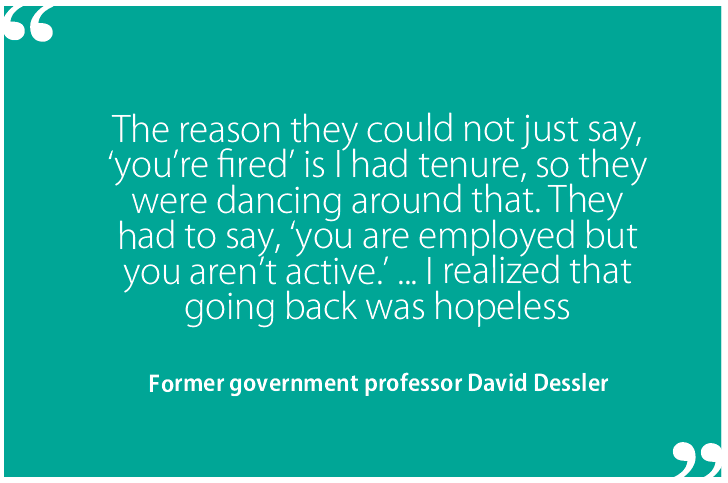

Overall, Dessler said he views the College’s Aug. 9, 2016, listing of his inactive employee status as “wordplay.”

“I lost all privileges of employment,” Dessler said. “The reason they could not just say, ‘you’re fired’ is I had tenure, so they were dancing around that. They had to say, ‘you are employed but you just aren’t active.’ … I realized that going back was hopeless.”

![]()

By Sarah Smith

Although the College of William and Mary states that former government professor David Dessler remained a tenured faculty member until his June 18, 2017, resignation, he has not been permitted on campus since November 2015 — roughly the same time he began an extended period of medical leave.

Monday, Oct. 26, 2015, following a week of uncertainty over the future of Dessler’s government courses, then-department chair John McGlennon informed students that their professor had been placed on administrative leave and would be replaced by new instructors.

In an interview with The Flat Hat, Dessler said he did not learn he had been placed on administrative leave until his students reached out to him.

Over the next several days, Dessler sent several “regrettable” emails to students, as well as McGlennon. These emails, he said, were the result of a condition called acute psychiatric trauma, which kept him from thinking clearly.

In a Nov. 2 phone call with Provost Michael Halleran, Dessler agreed to go on medical leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act entitled him to 120 days of unpaid leave, while the College’s leave policy enabled him to turn this unpaid leave into paid leave.

Dessler said that his decision to go on medical leave was spurred by grief over the death of his sister and a desire to seek treatment. He had previously taken medical leave in spring 2007.

“Focusing on tasks like when I had to do research, prep a lecture, I had a hard time focusing,” Dessler said. “… What made me decide to go on the leave was in part I wanted to get treatment, and I decided I didn’t really have a choice because they’d put me on this leave and were not offering a dialogue to get back to work.”

The Faculty Handbook states that although the need for extended leave is often unanticipated, faculty members are required to notify the Office of the Provost. If medical inability to work extends or is expected to extend beyond three weeks, a physician’s statement verifying inability to work, including an anticipated return date, is required.

Dessler said that in January 2016, he felt ready to return to work. March 2, 2016, Chief Human Resources Officer John Poma wrote Dessler that his paid leave would end March 24, a College-granted extension from the original end date of March 4. In the letter, Poma said that if a qualified medical provider had deemed Dessler fit to work, he must submit an updated FMLA form. If he had not been certified to return, he was eligible apply for long-term disability benefits.

March 8, Poma emailed once again, reminding Dessler that he had voluntarily taken medical leave and the onus of applying to return to work or seeking long-term disability benefits was on him.

March 14, Poma told Dessler that he had three options: elect to retire, submit the FMLA certification or apply for long-term disability benefits. If Dessler selected none of those options, his pay would end, and his health insurance would lapse March 31.

Just under two weeks later, March 24, the day his paid leave was set to end, Poma emailed Dessler once more, extending his paid leave to the end of the spring 2016 semester and reiterating the three options for proceeding.

FMLA return-to-work certification is also known as a “fitness-for-duty” certification, and an employer may only request it with regard to the particular health condition that required the employee to take FMLA leave. The employer may contact the employee’s health care provider to clarify and authenticate this certification.

According to Dessler, the certification document the College asked for did not fall under the legal parameters of FMLA policy. He said he offered to undergo a medical exam during both March and July but objected to filling out an “illegal” form.

“The process that actually occurred was not one that was fair or abided by the law because they kept saying you must turn in this form,” Dessler said. “I did a lot of governance work with the College [and] was a stickler for doing these policies correctly. I wasn’t resisting the exam, just resisting the illegal form.”

According to Dessler’s Nov. 5, 2015, leave paperwork, the reasons for his medical leave were grief and fatigue following the death of his sister and ongoing divorce settlement.

The FMLA only allows employers to ask for fitness-for-duty paperwork for the specific medical condition that an employee went on leave for, which means that the College could only ask Dessler to submit paperwork regarding grief and fatigue. It is not clear which condition Poma requested certification for.

By the end of the spring 2016 semester, Dessler had not turned in the requested form. Within two weeks of Aug. 9, 2016, when his employee status was listed as “inactive,” his pay and all associated employee privileges ended. According to the College, however, he retained his tenure status.

Although he was listed as tenured but “inactive,” Dessler claims that this was effectively termination (see section on termination for more details).

“The reason they could not just say ‘you’re fired’ is because I had tenure, so they were dancing around that,” Dessler said. “They had to say you are employed but you just aren’t active, I didn’t get paid.”

According to College spokesperson Suzanne Seurattan, Dessler’s inactive status was the result of him not taking any of the recommended actions to return from his paid leave.

She also said that there is no pay or benefit package associated with this status. One point of contention between the College and Dessler is that “inactive status” is not referenced in the Faculty Handbook.

“The Faculty Handbook does not cover all employee policies, procedures and regulations that pertain to tenured and tenure eligible faculty,” Seurattan said in an email.