In case you haven’t already seen it, read The Steam Tunnels Part One before reading this post. It’ll make more sense that way.

Our story picks up in the 90s, with a peculiar letter to the editor. Seemingly apropos of nothing, an alumnus wrote in to The Flat Hat to urge students to continue tunneling. Chronicling his exploits in the tunnels, including an incident where he temporarily shut off the power to the President’s house, he offered some tongue-in-cheek advice to students seeking to explore underground. He also cited the Flat Hat article from 1979, leading me to believe that he was the “Subterranean Snake” mentioned in said article. Don’t worry, the statute of limitations on trespassing is five years, I checked.

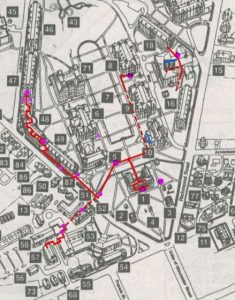

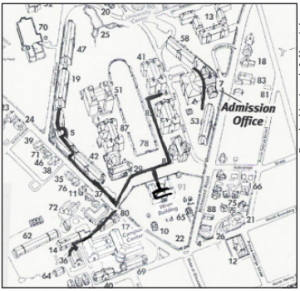

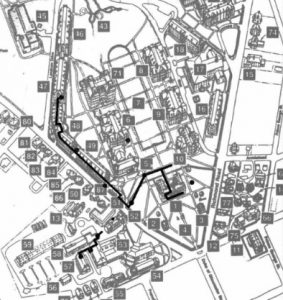

Whether compelled by this letter or simply following the exploration zeitgeist of the late 90s and early 2000s, records of tunneling began to trickle in. The best records I found are on a website from 1999, hosted by Yahoo Geocities. This site is truly an artifact, only accessible through Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Though the site was mostly used as a homepage for the owner’s punk/bluegrass radio show on WCWM, it also contained a page titled “W&M Underground,” where I found a vague map of the tunnels with some entrances marked. Along with the map, the author posted some photos of rooms, entrances and tunnels.

The author briefly describes some of the entrances on Old Campus, including several manholes. There are also entrances in buildings, however. Previous accounts discussed an entrance in Monroe Hall, but the author of “W&M Underground” favored the entrance in Barrett, calling it “the mother of all entrances,” and including a photo of the staircase leading down to the tunnels.

As a current resident of Barrett Hall, I can confirm that this entrance no longer exists. Perhaps tired of all the students entering the tunnels through the door, the administration completely sealed the stairwell with concrete.

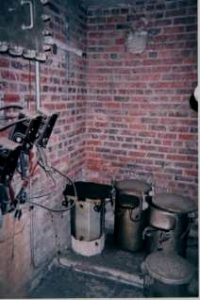

The author also mentions entrances in James Blair Hall and Chandler Hall, although both are likely padlocked to deter trespassers. The author lists some of their findings in the tunnels, including graffiti from the 60s, cans from the 80s and giant cockroaches that prowl underneath Blair. Most mysteriously, they posted a photo of a “secret room” apparently discovered in 1998.

This treasure trove of tunnel-related lore was the most detailed account I found, but it was far from the only one.

In an article from 2006 in The Virginia Informer, a defunct campus newspaper, another tunneler tells his story. Going by the pseudonym “John Doe Tunneler,” (much less interesting than “Subterranean Snake”) he provided a vague map of tunnels and entrances, many of which match up with the map from “W&M Underground.”

Otherwise, the article provides no more useful information, other than to caution students against the dangers of hot steam in the tunnels.

The last map I found is unattributed, simply an artifact left on an urban exploration site from the early 2000s. The author of this map is a mystery, but the entrances once again match up with the other two maps.

The iconography on all the maps looks fairly similar: the box around the Wren crypt, the dots for entrances, the tunnel fragments on the west side of campus. This leads me to believe these maps all come from a single source, probably the owner of “W&M Underground.” Thanks to this intrepid explorer, we have a better idea of the extent of these tunnels and how the puzzle pieces fit together.

I started this story with a legend about the consequences of tunneling, that students caught in the underground passageways are immediately expelled with no questions asked. From the past accounts of tunnelers, this clearly isn’t true. So why do we have such mythology surrounding these banal thoroughfares for electrical wiring and steam?

For one thing, the lack of information contributes to the mythos. The tunnels combine 1850s technology with 1700s storm drains, leading from dorms to crypts and back again. Students at the College are curious, naturally drawn to secrets and padlocked doors, dark stairwells and clandestine passageways. With only vague admonitions from the administration, who can blame twamps for their curiosity?

In my opinion, accounts of the tunnels are too few and far between. With no real map of the tunnel system, relying on snippets of blog posts and whispered rumors of expulsion, the underground passages seem much more romantic than they really are. Full of dirt, mechanical equipment and steam pipes, the tunnels are really only useful as a superhighway for cockroaches. Like the mysterious underground passageway found in 1924, the rumors and speculation are more interesting than the truth.

Over the years, the administration has tried to deter students from tunneling. With alarms and padlocks, oral reprimands and trespassing charges, the number of students in the tunnels has dwindled down to an intrepid few. But let’s be honest: twamps will always tunnel. The administration’s vague threats and lockdown on tunneling information only contributes to the dramatization of underground exploration. In my opinion, the only way to get students to stop is to be open about what’s down there: absolutely nothing. I think it’s time to bring these underground tunnels into the light.

Your article was wonderful; I found it very interesting. I was wondering if you could post/send me the url/link to the web page you found in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine (the one from 1999 titled “W&M Underground”) . I’d like to read the original web page (for research purposes only) and I can’t seem to find it any where in the Wayback Machine.