The college admissions process has come under increased scrutiny in recent years, particularly at elite universities where parents are ready to pay millions to get their kids in the door. As the parents of Operation Varsity Blues face trial over the coming months, the coaches, tutors and exam administrators that made the manipulation possible are also under investigation.

Most students admitted through the scandal were pegged as talented recruited athletes, except they weren’t. How these parents cheated the system, though, has been a question involving a network of coaches and athletic officials, putting university athletic departments in the hot seat.

The College of William and Mary was not implicated in Operation Varsity Blues, and there is no evidence that any students have bribed their way into the College. Still, in the aftermath of the college admissions scandal, other perfectly legal methods of gaining an edge in the admissions process have been criticized. Certain subsets of prospective students — notably legacies and athletes — are said to come from wealthier backgrounds and have an easier time gaining admission to the nation’s most prestigious institutions.

Students and parents across the country have made claims about the ‘athletic advantage,’ both at the College and at other institutions, whether through colloquial arguments or data-backed opinions. The consensus is usually that recruited athletes, with the backing of coaches, have their applications easily moved to the elusive ‘yes’ pile. But is this assumption fair?

Dean of Admissions Tim Wolfe said that yes, recruited student athletes do receive recommendations from coaches before an admissions decision is made. But Wolfe said the advantage isn’t that simple.

“As a Division I NCAA institution, we need to realize that that essentially means these student athletes that are being recruited by our coaches and, in turn, the athletic department — what that really means is these are students that have a national, I think sometimes you could say even international, caliber-level talent,” Wolfe said.

While athletes fill out the same application and receive the same offer of admission from the Office of Admissions itself, the office does provide “preliminary feedback” on prospective recruits.

Not all students with “international caliber” talent would receive the same treatment, however. Wolfe said that the difference between an applicant who is an athlete versus a world-class debater would be in the evaluation of talent.

“I’m going to have a hard time saying equal footing because it depends on how that information is presented and vetted,” Wolfe said. “In terms of athletics, you have a situation where we have professional staff and evaluators and coaches who are able to say that this is a student with this national-level talent.”

Wolfe emphasized that athletes at the College undergo rigorous recruitment, not just for their sport, but they must also live up to the College’s academic standards. He said the admissions office recruits holistically for a class, working with Tribe Athletics to ensure both entities’ standards are met.

“And to do that requires us to work together,” Wolfe said. “What makes that a challenge and no easy task is recognizing that that includes both the competitive landscape involved in recruiting student athletes at the Division I level, while also ensuring that our incoming student athletes are prepared to succeed academically when they get to the university.”

On the athletic side, recruitment usually takes place at showcase tournaments, which bring together club and travel teams across the country to demonstrate their skills in front of college coaches and recruiters. Assistant Athletics Director for Compliance Paul Cox said roughly 90% of athletes at the College are recruited, meaning they have had some contact with coaches prior to applying.

“Recruiting is obviously going to be different sport-by-sport, but a majority of what it’s going to be is these larger showcase events where it’s just easier for a coach to get to a big event where there’s multiple teams from different locations,” Cox said. “They’ll just sit down and observe there and evaluate based off that. If they spot somebody who has the talent they’re looking for and who they think may be a good fit for William and Mary.”

From there, recruiters ask prospective athletes about their academic record before requesting an evaluation from the Office of Admissions on a candidate’s admissibility.

Due to expenses related to athletes attending showcase events, Cox said the athletic department still recruits at high schools.

“There’s not just these club sports, but the high schools that have it as well,” Cox said. “Coaches can still get to the high school events and tournaments — they’re still going to all of those. Some of the bigger showcase events is where it’s happening, but it’s also coming from high schools.”

Director of Student Activities at Langley High School Geoffrey Noto said recruiters rarely visit his school.

“The majority of the recruiting, except for football, goes through club and travel programs,” Noto said. “That recruiting is happening outside of the school. Right now, we have some college football coaches coming through — we’ve had some kids go to William and Mary and play football before — but that’s really the only sport where they actually make appointments, come to the building, meet with kids, talk about their programs.”

Socio-economic Background

While the admissions process for athletes may be remotely similar to that of the non-athlete, potential advantages for prospective student athletes do not solely begin when the applicant has the first conversation with a college coach. The journey to becoming a college athlete begins at a young age, and the resources required to participate in elite sports are costly.

The Flat Hat collected data on hometown median household income and high school type for all College athletes, according to public information and rosters. The analysis concluded that College athletes, on average, come from more socioeconomically privileged backgrounds as compared to the average non-athlete student at the College.

The average hometown median household income for all College athletes is $96,981.89. The median is $86,420. The College does not collect household income data for individual students, nor for individual athletes. That said, this figure is significantly higher than the nationwide median household income of $68,703.

Only 6.5% of athletes receive Pell Grants, compared to 12.14% of the overall undergraduate student body. Pell Grants, which are determined by the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, are often awarded to families with an income below $50,000 — and often below $20,000 — but they do not capture all students who are considered ‘low income.’ Likewise, 9.87% of athletes identify as first-generation college students, as opposed to 11.43% of the student body. While athletes are less likely to receive Pell Grants and identify as first generation, this does not mean all athletes are wealthier than the average student. Rather, in the aggregate, athletes skew higher in income than the student population as a whole.

There were several teams that had particularly high average median household incomes, including lacrosse, with a MHI of $128,479.21. Men’s tennis has an average MHI of $131,910, though over half the team is composed of international students, for whom MHI was not calculated.

While often considered among elite universities, the College’s athletic demographic does vary from other elite private colleges, such as the Ivy Leagues.

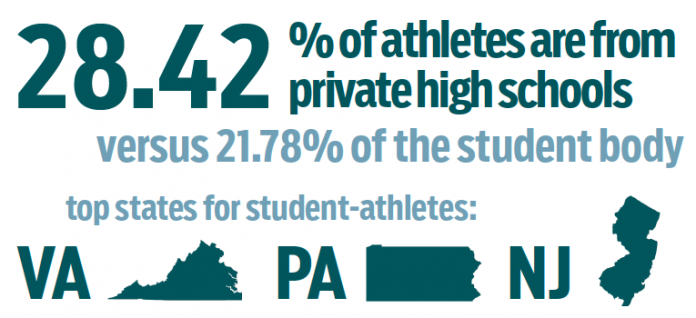

First, the College is a public institution. Like the rest of the student body, athletes are more likely to be from Virginia than any other state. While the overall student body is roughly 64% Virginians, only 45% of athletes are in-state students. Student athletes were most likely to come from Virginia Beach (14), Richmond (12), Vienna, VA (9) and Alexandria, VA (8). Other states that send a significant number of athletes to the College include Pennsylvania (10%), New Jersey (8%) and Maryland (6%). These demographics differ from those of the Ivy League schools, however, which see more significant concentrations of athletes from Connecticut’s Gold Coast and Fairfield county, New York’s Westchester county and Boston’s wealthy suburbs.

Second, the College recruits fewer athletes than Ivy League schools. Despite having similarly sized student bodies, Princeton has more than double the number of student athletes. The Ivy League sponsors 34 sports, including fencing, ice hockey, squash and rowing — sports with high costs and larger barriers to entry. In contrast, the College fields 20 teams. The Harvard Crimson revealed in survey data of the class of 2022 that 68.8% of recruited athletes’ families make above $125K. While the exact household income is not available at the College, only 22% of College athletes have a hometown household median income above $125K. Thus, disproportionately richer student athletes make up a greater part of the student body at Ivy League colleges.

Despite these differences, Ivy League schools and the College both heavily recruit athletes from Northern Virginia — mainly the affluent suburbs of Washington D.C. Three of the top 10 richest counties in the United States are located in Northern Virginia: Loudoun County (MHI $134,464), which is the richest county in the country; Fairfax County (MHI $115,717); and Arlington County (MHI $110,388).

The Private v. Public Divide

There are 461 athletes at the College, according to public rosters. Roughly 28.42%, or 131, of those athletes attended private high schools. For the student body as a whole, that percentage is 21.78%. The median private school full tuition for College athletes was $24,500, barring financial aid and scholarships.

Nationwide, about 7.24% of college students attended a private high school. At some schools, such as Barnard, Washington and Lee, or Notre Dame, the percentage of students coming from private schools hovers around 50% or more. On the lower end of the spectrum, the University of California system matriculates fewer than 14% of in-state students from private schools.

While some public schools are better funded than others due to higher property taxes in the area, tuition money grants private schools the ability to invest in robust resources. Most private high schools boast a 100% four-year college acceptance and matriculation rate and many place students into elite colleges. Private schools often have more guidance counselors to support students in the college admissions process, whereas public schools must assign on average nearly 500 students to one counselor.

While tuition fees often rival those of private universities, private schools say they give anywhere from 1.5 to 4 million dollars in financial aid annually. The percentage of students receiving financial aid at these schools varies greatly — falling between 15 and 80%, with students receiving varying amounts in grants and scholarships based on demonstrated financial need.

Despite the prevalence of privately educated athletes at the College, the two high schools that matriculated the most student athletes are both public. Langley High School, a public high school in Fairfax County, currently leads the pack with six athletes. Blacksburg High School follows with five athletes.

Among private schools, Trinity Episcopal (full tuition $25,800) sent four athletes, and Georgetown Visitation (full tuition $32,600), The Bullis School (full tuition $49,740), St. John’s College (full tuition $22,100) and St. Stephen’s and St. Agnes (full tuition $44,830) all sent three each.

But for the most elite athletes, potential high school tuition is only one of many costs.

Noto, who has overseen Langley’s athletic department for 11 years, said club sports are near-essential for aspiring college athletes.

“I would say every single kid who has gone on to play Division I and Division II has played that sport outside of the high school,” Noto said. “Yes, every single student — they’re not just playing their sport for their school, they’re playing outside of their school. At Langley, 90% of kids who play a varsity sport and play meaningful minutes also play that sport for a club team.”

“I would say every single kid who has gone on to play Division I and Division II has played that sport outside of the high school,” Noto said. “Yes, every single student — they’re not just playing their sport for their school, they’re playing outside of their school. At Langley, 90% of kids who play a varsity sport and play meaningful minutes also play that sport for a club team.”

The fees associated with club sports, from travel expenses, tournament entry fees and coach salaries, can be high.

“The out-of-pocket expenses at the high school level is minimal compared to club,” Noto said. “You’re talking ten thousand dollars a year to be on a club team. We have a lot of girls, for example, who play volleyball here, who are really good volleyball players, and then also every weekend they are going to New York, Philadelphia, Orlando — and those costs must be exorbitant.”

The Data, Explained

Athlete hometowns and high schools were aggregated from team rosters, which are publicly available. Of high schools that were private, or otherwise charged tuition, tuition and financial aid figures were drawn from school websites. All median household income figures were derived from official U.S. census data.

While the data points come from individual athletes, no athlete’s information has been singled out in this story. Instead, all data has been discussed in the aggregate or anonymously. Figures for the student body in its entirety were provided by the College’s Office of Institutional Research.

Large-scale data figures can give insight, but there are also realities that they may not capture. A first caveat is that while full tuition numbers are discussed in relation to private high schools, not all students who attend private high schools pay full tuition. Private high schools often provide scholarships to students with demonstrated financial need, which often cover all or most of the sticker price.

Private schools may not be the only place in which privilege manifests. Charter schools, magnet schools and elite public schools are all tuition-free high schools that provide students a similar wealth of resources and opportunities that poorly-funded public schools may not provide. Public schools are also funded by property taxes, and thus areas with higher incomes and more expensive homes have better-funded public schools.

Likewise, the median household income is an overall statistic — it does not reflect individual household wealth, but is rather a good indicator of the socioeconomic status of a family living within that town or city. For large cities in particular, MHI may not be as useful since there are disparities between neighborhoods. For example, in New York City, which has sent three current athletes to the College, the overall MHI is $63,998. That number does not represent, however, the fact that the highest MHI in the city, in the 10282 zip code of lower Manhattan, is $250,000+. On the other hand, the lowest is in zip code 10454 in the Bronx, of which the MHI is $21,447.

While not all towns and cities experience such vast wealth disparities, this example demonstrates that MHI is not fully representative of any individual’s wealth. To determine the wealth inequality within a place, statisticians typically use a Gini coefficient, though this measure is not widely available for individual towns and cities. MHI is the most used and most collected indicator of socioeconomic status, and thus it is used to represent relative wealth in this dataset.

The data does not include the MHI for international athletes, since this data would not be collected by the Census Bureau and would thus be inconsistent with domestic MHI data.

Making judgements on students based on their “hometown median household income” and whether or not they went to private school is a bit crass, don’t you think?

What was the goal of this article? What purpose does it serve?