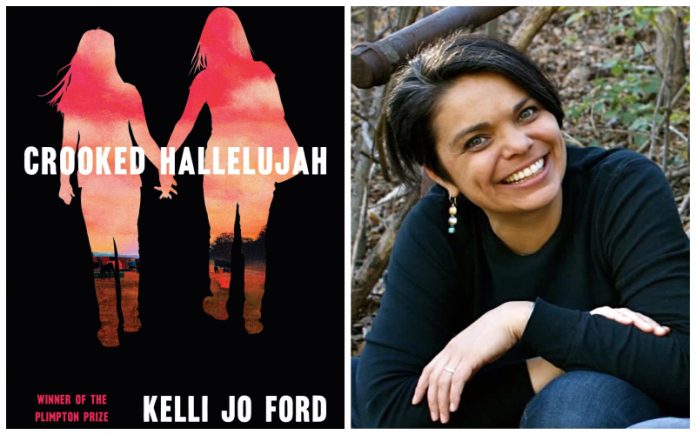

Thursday, Nov. 10, the College of William and Mary’s 2022 Donaldson Writer-in-Residence Kelli Jo Ford read an excerpt from her debut novel “Crooked Hallelujah” at the Reves Center for International Studies. “Crooked Hallelujah” was long-listed for numerous awards like the Story Prize, the Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction and the PEN/Hemingway Prize. Ford’s writing is inspired by her personal experiences growing up as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma.

“Crooked Hallelujah” was initially conceived as short pieces. After holding on to each story for a long time, they were interwoven into a full-length novel. English and American studies Associate Professor Arthur Knight described the effect of this format.

“I like, as a reader, getting to do that imaginative work of connecting the different chapters and sometimes having to sort of fill in your own sense of what could have happened in this big gap between chapters,” Knight said.

“Crooked Hallelujah” spans many years, following the life of a mixed-blood Cherokee woman named Justine, and eventually that of her daughter Reney.

“The book was inspired by the relationships between the women of my family. Like Reney, I grew up in a household with four generations of Cherokee girls and women, and had a really close relationship with my mom but especially my great-grandma.”

“The book was inspired by the relationships between the women of my family,” Ford said. “Like Reney, I grew up in a household with four generations of Cherokee girls and women, and had a really close relationship with my mom but especially my great-grandma.”

Ford read the portion of the novel which takes place in Eastern Oklahoma’s Indian Country during the 1980s. Ford’s prose sang with rich, vivid details, highlighting the fascinations and tribulations of everyday life. The excerpt begins with Justine, Reney and another young woman applying makeup in a bathroom while discussing their hopes for the future.

“We’ll be in our own place before we know it,” Ford read from the perspective of Reney. “We’ll probably get a pink Cadillac and drive to Dallas and then dine with Mary K herself.”

Justine and Reney’s current circumstances are not without their challenges. The other women in their family, Granny and Lula, differ from Justine with regard to their views on religious customs and a woman’s modesty of appearance and manner. Justine must work a second job at the cowboy bar in order to make a living for herself and her daughter. A significant source of tension was the abusive treatment that Justine is subjected to by men, which has reverberating effects on her relationship with Reney.

Leah Tutton ’23 reflected on these relationships.

“I think abusive relationships are one of the most difficult things that any person can go through, and in a way it both, especially with the mother and daughter relationship, drives them together, but also creates an awkward wedge,” Tutton said.

The intersection of misogyny and racism is an underlying presence throughout the passage. In one harrowing scene, Reney steals a gun from a man her mother is spending the night with. She fantasizes about escaping to the comfort of her Granny’s house and burying the gun, preventing anything dangerous from occurring. The man berates Reney after he discovers it is missing and Justine compels him to leave.

“Reney hears him shout ‘about like a bunch of Indians’, and runs over to the window in time to see him yanking open the door to his truck,” Ford said as she detailed Reney’s perspective about the frightening encounter.

The novel also demonstrates how Reney’s observations of her mother’s relationships have negative impacts on her own mindset.

“I was interested in continuing to push the idea that Reney has come to think of love as something that’s used as violence.”

“I was interested in continuing to push the idea that Reney has come to think of love as something that’s used as violence,” Ford said.

The struggles of whether or not to stay in touch with one’s culture are also explored throughout the novel. There is a persistent lack of opportunities on the reservation, largely due to the ramifications of colonialism. After the conclusion of the excerpt, Justine and Reney travel with a man named Pitch to Texas, the idealized place they had dreamt of for so long. Nevertheless, there is a powerful loss in moving away from the Cherokee Nation.

“I think Pitch comes across as a generally benevolent presence in Reney’s life, but I feel like there’s an undertone of trouble, particularly in how he poses the threat of distancing Reney from the rest of her family,” attendee Jenna Massey ’24 said.

Reney is no longer growing up alongside people who share the customs of her heritage or know how to speak the native language. Nevertheless, both she and her mother continuously feel drawn back to the place they left behind.

“In spite of the trauma involved in the stories, I think there’s a great mourning of love and connection,” Ford said.

The brief glimpse into Ford’s novel “Crooked Hallelujah” spoke volumes about the enduring emotional ties of family and the tensions between loving one’s home and the desire to become independent from it.