Wednesday, March 22, the College of William and Mary Religious Studies department hosted a lecture titled “Witnessing the Recovery: Storytelling and Family Building from Belsen to Ireland” presented by visiting assistant professor of judaic studies Mary Fraser Kirsh. Walter G. Mason associate professor of religious studies Kevin Vose introduced the lecture, which serves as part of the department’s annual research presentation series..

Kirsh’s lecture, based on her ongoing book project titled “Writing the Recovery: Stories of Rehabilitation in the Post-Holocaust Era” follows the stories of three individuals who acted as caretakers for children displaced by the Holocaust: Murial Knox Doherty, Dr. William Robert Fitzgerald Collis and Olga Eppel. Kirsh’s goal is to introduce audiences to ordinary people who aided in trauma healing and storytelling in order to contribute to the rehabilitation of young Holocaust survivors.

“These caretakers are really uniquely positioned,” Kirsh said. “They were influential actors in a massive process of rehabilitation. They were listeners of their ward’s stories, and they were also storytellers in their own right.”

“They were influential actors in a massive process of rehabilitation. They were listeners of their ward’s stories, and they were also storytellers in their own right.”

Kirsh mentioned that their stories provide an outline for how people found normality in their lives following a genocide, as well as how these caretakers navigated social norms, emotional connections and the complex process of recovery. Kirsh began her lecture by acknowledging contemporary displacement and the global refugee crisis.

“Before I introduce you to these individuals more, I also want to note that today we are experiencing worldwide a refugee crisis that we haven’t seen since this immediate postwar period,” Kirsh said. “There’s about 89 million refugees around the world at the moment. One out of every 113 people are currently displaced. And so I’m interested in those stories and who’s telling those stories and how.”

Kirsh then described the lives and efforts of her research subjects, beginning with Doherty, who served as a nurse in the Australian Army and Air Force during World War II. In 1945, Doherty was awarded the Royal Red Cross Medal, First Class and joined the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, becoming the chief nurse of Bergen-Belsen — a displaced persons camp which formerly operated as a Nazi concentration camp before it was liberated in April, 1945.

Doherty’s primary task was to transform the emergency hospital on the grounds into a relatively normal-looking medical institution. Though Doherty faced a variety of challenges while operating with a small staff with limited experience, she also made an effort to act as a storyteller by leaving behind many letters and records from her time at the hospital.

“Her letters also show the emotional weight of witnessing and the practical work of writing, that this was a really strenuous thing,” Kirsh said. “Storytelling, it turns out, requires energy and it requires resources. But regardless, her witnessing is happening on a daily basis.”

Kirsh described Doherty’s desire to not only be a healer and listener, but also a messenger of the horrors of the war to a sheltered audience back in Australia. Doherty was also interested in the concept of family rebuilding and mentioned the extensive number of pregnant women and displaced children placed in her care.

“She says, ‘unless the future of these homeless people is solved, all the work carried out will have been in vain. If they’re going to go out into a hostile world to again struggle against overwhelming odds, they might have been better off had they not survived,’” Kirsh said.

Kirsh continued the lecture by describing the efforts of Collis, an Anglo-Irish physician. Collis was particularly interested in working with children, and he later volunteered for the British Red Cross —taking a position at Bergen-Belsen where a children’s hospital had recently been built. Collis aided in overseeing the care of displaced children and became invested in the family rebuilding process.

“Despite the fact that there was absolutely no legal provisions for adoption in Ireland, despite the fact that the private adoption of Jewish survivors was incredibly rare, even by Jewish families and Collis was not Jewish, he was allowed to bring six orphans with him back to Dublin, where they would remain under his care, assuming that nobody turned up to claim them,” Kirsh said.

Collis ended up writing four memoirs, three of which reflect on his experiences in Bergen-Belsen. Collis battled with the appropriate ways to help children and formed a connection with a fellow caretaker, Hans Hogerzeil, in the process. After adopting two of the six children who he had taken back to Dublin — the four others placed in other homes — his entire family changed.

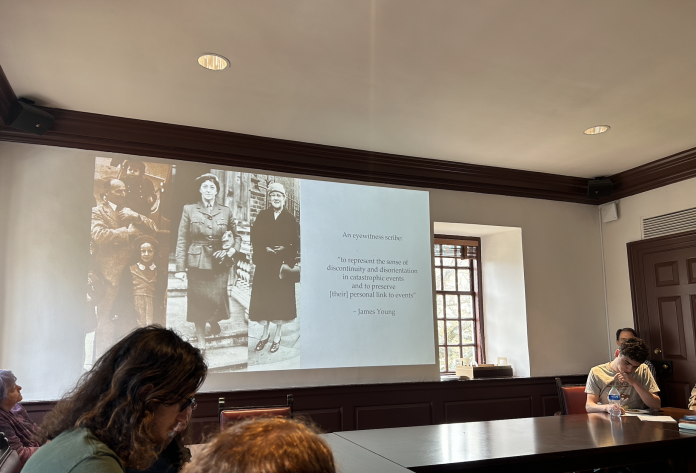

“Collis’s work as an eyewitness scribe reveals that emotion played a powerful role in rehabilitation, and this love resulted in his entire family eventually being restructured,” Kirsh said. “Eventually Collis would divorce his wife, Phyllis, marry Hogerzeil and create a new, complicated family born out of connections made and social norms they challenged in the postwar period.”

“Collis’s work as an eyewitness scribe reveals that emotion played a powerful role in rehabilitation, and this love resulted in his entire family eventually being restructured.”

Kirsh concluded the lecture by telling the story of Eppel, an Irish, Jewish woman who presumably worked as a sergeant clerk in the British Army. During the postwar period, she likely served on the Dublin Jewish Ladies Committee. She was later hired by Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld as the manager of Clonyn Castle, a building that would be used to house and care for displaced children, brought to Ireland, as part of Shonfeld’s Religious Emergency Council.

At the time, this was a difficult task, as Ireland had instigated a policy of restricting Jewish immigration due to potential social problems. Unlike Doherty and Collis, Eppel had an immediate desire to stave off anti-Semitism and urged children under her care to act as ambassadors of Judaism in Ireland.

“Eppel’s account, which she is writing as this work is being carried out, portrays a time marked by chaos,” Kirsh said. “The immediacy of these letters provides us a behind-the-scenes look at the daily struggles to provide a stable, albeit very short-lived home. She is writing and working from within Ireland’s Jewish community, she is dealing with stresses brought by the war, she is dealing with years of continuing anti-Semitism.”

Kirsh opened the floor to take questions from the audience and discussed the larger importance of Holocaust testimony work and caretakers as a whole.

“There’s a great Holocaust scholar, Dori Laub, and he said this of listeners of Holocaust testimony. He says ‘the listener to trauma comes to be a participant and a co-owner of the traumatic event. Through his very listening, he comes to partially experience trauma in himself.’ And that is certainly true for the individuals that I introduced to you today. They’re working to metabolize their ward’s stories, they’re articulating their own trauma that they experience while navigating this messy apparatus of recovery,” Kirsh said.

Daniel Brot ’23 attended the event and plans on writing about Kirsh’s work for the undergraduate journal, the Judaic Studies Review.

“My main takeaway is how there are stories on the margins of history, but also there are times on the margins of history,” Brot said. “I think it’s really important to understand that real people have to fix things and that it’s the real kindness and the real kindness and the real hard work and the suffering of care workers who help get over problems like this.”

“I think it’s really important to understand that real people have to fix things and that it’s the real kindness and the real hard work and the suffering of care workers who help get over problems like this.”

Vose, who introduced and concluded the event, said in an email that Kirsh’s work brings to light stories that have been overlooked.

“Her archival work brings some of these accounts to light for the first time, telling compelling and long-forgotten stories,” Vose said. “Her work highlights individual caregivers and their extraordinary efforts to help children of the Holocaust heal and create new lives.”