The following article was previously published on The Flat Hat’s website during the week of Oct. 9. However, due to an unforeseen technological glitch, it was removed from the website for a period of time and was re-uploaded today, Nov. 6.

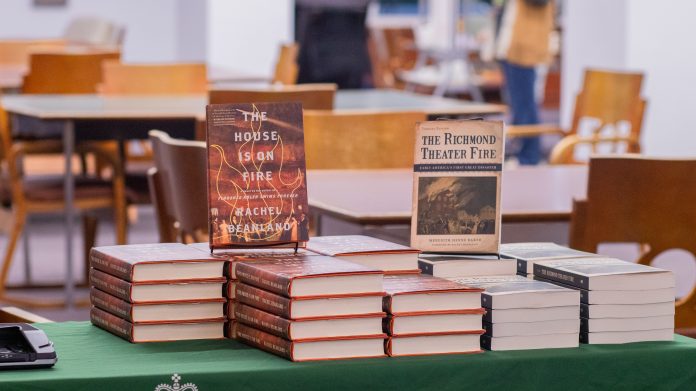

Thursday, Sept. 28, the College of William and Mary’s Special Collections Research Center at the Earl Gregg Swem Library hosted authors Meredith Baker M.A. ’07 and Rachel Beanland to discuss their books on the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. This event was sponsored by the Molly Elliot Seawell Endowment, an initiative dedicated to supporting female authors in Virginia.

The hour-long discussion, moderated by associate professor of creative writing and English literature Brian Castleberry, attracted students and Williamsburg locals familiar with both authors.

Baker, a writer based in D.C., began the initial research for her nonfiction book, “The Richmond Theater Fire: Early America’s First Great Disaster,” as a graduate student at the College.

The book was published in 2012, later winning the Jules and Frances Laundry Award and Phi Alpha Theta First Book Award.

In part, Baker’s work inspired Richmond novelist Beanland to begin working on her fiction novel, “The House is on Fire”, which is based on the same topic. Beanland’s novel was published in April 2023 and has garnered attention from the Washington Post and Good Morning America.

Both authors’ main attraction to writing about the Richmond Theater Fire was its significance amidst its progressive fading from modern consciousness.

According to Baker and Beanland, in an era situated between the American Revolution and Civil War, Richmond, Va. in 1811 was a relatively small town with a population of 10000. The town was split on the basis of race between white individuals and enslaved Black individuals. In the early 1900s, Richmond was known for its gambling and horse racing, musical performances and amusement parks.

The general lack of records from this time presented a significant challenge to both Baker and Beanland when attempting to accurately depict the historical context in their work.

“Well, I was a little jealous of people who had written things closer to the present because it would have really been wonderful to have photographs of some of these places and people,” Baker said. “But we don’t, for example, have a really good drawing of what the theater looked like. But I pieced together, I don’t know, 40 different accounts of people who were in it and jigsaw-style put it together.”

Castleberry was fascinated by their great effort to bring this historical event back to life.

“Their two books opened up that era for me,” Castleberry said. “Especially Meredith’s, you know, really do resound with so many aspects of what life was like around this time. The way they were talking about it, I feel like is really true.”

According to the authors, on the night of Dec. 26, 1811, the Richmond Theater was packed at about 20% over-capacity for a double-header play production. Towards the end of the second act, a raised chandelier set the roof ablaze. Within minutes, flames had engulfed the whole hall. Shortcomings in the building’s construction made escape nearly impossible, resulting in the death of 72 individuals at the scene, including 42 women and six Blacks.

For Baker and Beanland, their focus was less on the fire’s origins and more on its aftermath, particularly through examining what was documented and what was omitted from records.

Both authors emphasized the importance of incorporating female and BIPOC perspectives to provide a more accurate and comprehensive narrative of the incident.

“I was certainly very interested in that angle, in which Meredith does a lovely job talking about in her book. And I felt sure that there was a story there, because you know 72 people died and 42 of them were women. There’s a story. And so for me, it would have felt like an incomplete book not to spend some time focusing on that,” Beanland said.

An often-overlooked historical figure featured in both authors’ works was Gilbert Hunt, an enslaved blacksmith who caught multiple people who were being thrown from burning windows.

For both authors the inclusion of slavery, racism and misogyny prevalent in early 19th century Virginian society was vital to incorporate into their storytelling. This choice to include such topics, however, has fostered discontent with some readers

Beanland recounted a recent disinvitation from a book event at a Jewish Community Center in Florida due to her portrayal of slavery in her novel.

“When I set out to write this novel, it wasn’t like I necessarily set out to write a novel about slavery,” Beandland said. “I set out to write a novel about the Richmond Theater Fire. But the reality is, you can’t write a book about Richmond, Virginia without addressing slavery. And I think people who live in Virginia know that. You know, I think we are very aware of the fact that you can’t tell a story without talking about slavery, but I think that in other parts of the country, that is more difficult to wrap your head around and maybe there are parts of the country that pretend you can tell these stories without it.”

Following the talk, both authors answered several audience questions during a light reception in Special Collections.

Special collections student-employee and English major Harrison Clingman ’26 listened to the discussion from the front desk.

“I’ve never heard of either of them and their books before, but I had been working with some of their theses downstairs and it’s definitely interesting to hear some of their voices who have actually been through the whole doctorate, Masters and Ph.D program here,” Clingman said.