John Powers ’26 is a Public Policy major hailing from Brooklyn, NY. He is a Resident Assistant in Hardy Hall, a member of the Undergraduate Moot Court competition team and a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. John is a huge Adele fan. Email him at jdpowers@wm.edu.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

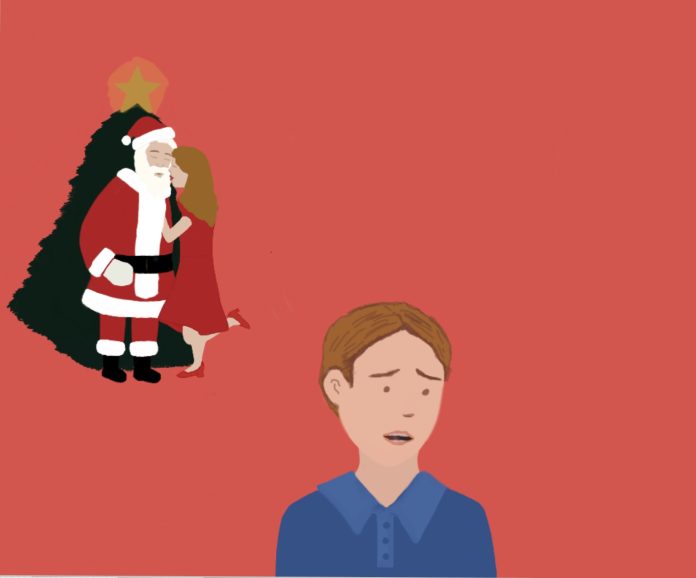

It’s that time of year again. The sun is setting earlier, and the temperature is getting colder. Stacks of red and green holiday cups sit on Starbucks counters. As shoppers weave through crowded aisles buying Christmas presents, Mariah Carey’s whistle tones fill the air. And, like always, masses of children are being indoctrinated into believing in Santa Claus. It is time we take a second look at this tradition.

A viral YouTube video may tell us why. In 2016, Cut uploaded a video of parents telling their children Santa Claus is not real, garnering 5.8 million views. Most of the childrens’ reactions were innocuous at first glance. Some frowned. Others looked shocked.

“I told you. I told you,” exclaimed a young girl upon learning the truth.

From the many reactions shared in the video, that of one boy stood out to me. As he denied what his parents had told him, his parents asked him questions to convince him of the truth. “Have you ever wondered how Santa could be at every mall in all these different places?” his father asked. His son retorted, “the more people that believe in Santa Claus, the more power he has to fly.” Similarly, the boy’s mother recounted how her son had once asked how Santa could not get burned coming down a hot chimney, to which the boy replied with another illogical response.

A common theme among the childrens’ reactions is that they had already begun questioning the existence of Santa Claus, but their parents prevented them from coming to the obvious conclusion. Why else would a child say, “I told you so?”

Instead of honoring their children’s logical doubt by admitting Santa Claus is not real, many parents refuse to tell the truth until children are the “right age.” I’ve heard some parents talk about their desire to “let kids be kids.” They would rather tell their doubtful five-year-old to believe in Santa than affirm their skepticism so as to keep the “magic” alive and preserve innocence. This desire to extend the tradition longer than its natural, believable timeframe is selfish.

Isn’t it more magical to treat their child’s intellectual maturity as a milestone? If a child is able to deduce that Santa Claus is implausible, parents should celebrate their child’s growing intellect and capacity for critical thinking by confirming their child’s intuition. While it may be a tough pill to swallow at first, this practice is ultimately more fulfilling than parents abruptly telling the truth after coercing a belief in Santa for years.

In two jointly published 2016 studies, researchers found that parents endorsed a belief in Santa regardless of age. In other words, even at the age children naturally begin to question the existence of Santa Claus, parents treat the situation the same. According to the researchers, the more parents promoted the reality of Santa Claus, the less likely children were to doubt his existence. Counterintuitively, the study found that higher exposure to people dressed as Santa Claus resulted in more of a belief that those people are the actual Santa.

All of this research suggests that the perpetuation of this Christmas tradition often hinges on parental reluctance to let go, arguably fueled by a desire to shield their children from the perceived loss of innocence.

The tradition is also fraught with adverse consequences. By now, the most obvious problem with the tradition should be its disregard for critical thinking. By enabling their children to believe in a character fantastical beyond reason, parents may foster a predisposition for children to accept information without questioning its validity. If Santa Claus is real, then why isn’t the monster under the bed real, too? We see this reflected in the video with the young boy who gave logically inconsistent responses to his parents’ questions.

Kids believe in imaginary concepts, but Santa Claus is unique in that adults not only confirm the existence of, but also instill a belief in this imaginary concept.

It doesn’t end there, though. Our Santa Claus tradition creates societal stigma within families and schools. We all know that one kid in fifth grade who still believed in Santa Claus and was the subject of gossip by everyone in the class. Educators often find themselves navigating a delicate balancing act, sometimes having to contend with parents adamant about preserving the illusion.

Children who find out later often feel a sense of embarrassment, since they were the last of their peers to find out. This stigma does not go away; peers may make fun of that child even after the truth is revealed, eroding their self esteem.

In the end, Santa Claus is a tradition of lying. We cannot blame broader society for perpetuating the tradition when we make active decisions to perpetuate it ourselves.

No one is forcing a parent to write “from Santa” on a Christmas present. No one is forcing a grandmother to show her grandchildren an app that pretends to track Santa’s movements around the world. No one is forcing a father to say Santa will enjoy the cookies and milk his child made, knowing full well that he will be devouring them as soon as the child is asleep. There is a breathtaking level of deception involved in this tradition, and it’s time to admit it.

Ordinary morality tells us that lying is wrong unless we can find some sufficient justification. Some may say that Santa Claus is a white lie. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries defines white lies as “a harmless or small lie, especially one that you tell to avoid hurting someone.” Everything discussed in this article contradicts the notion that the lie of Santa Claus is harmless or trivial.

Others may contend the lie is justified to advance the Christmas spirit. Really?

Christmas should be about gratitude, yet the thankfulness for gifts is given to an imaginary person rather than parents who in many cases, had to save money and work hard to buy those gifts and make their children happy. Instead of lining up for church or Christmas caroling for the elderly, parents line up their kids at the local mall so that they could tell a man playing dress up all their consumeristic desires.

So, what now? As you may have noticed, I’ve oscillated between criticizing aspects of how this tradition is practiced and the tradition itself at large. The truth is that it is hard to provide a solution to since it’s such an ingrained tradition. Perhaps we ought to give some deference to past generations who have found this tradition suitable, but on the other hand, isn’t that just doing something for the sake of doing it? “The Lottery,” by Shirley Jackson, comes to mind.

Finally, I will say this: parents should tell their children the truth or help them discover it as soon as some doubt creeps in (or by the age of seven). Even in childhood, we should not be fearful of ruining some perceived magic.