Ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the country’s sixth best public university for undergraduate teaching, the College of William and Mary is recognized as a prestigious institution of learning. The College relies on its educators to uphold the quality of education, but a question stands: How does the College compensate its professors? We collected publicly available salary data to assess how the salaries of professors at the College compare within the school and across other comparable institutions.

In 2022, the Faculty Assembly outlined seven priority areas where they identified a need for dialogue and progress at the College. One of the seven was to increase faculty salaries. In a statement, the Faculty Assembly pointed out that salaries did not increase in the 2018-2019 or 2020-2021 academic years. They also insist that low faculty salaries make it hard to recruit talented faculty, retain the talented faculty that the school currently has and reduces the morale of the current faculty.

The professors at the College generally reside under the umbrella of three different categories: teaching professors, tenure eligible professors and tenured professors.

A teaching professor is someone who is hired for the sole purpose of teaching, with no research responsibilities. Before 2024, a teaching professor would have the title “Lecturer,” “Senior Lecturer” or “Instructor.”

A tenure eligible professor is someone hired on the tenure track, who may be eligible for tenure after their third year at the College. They additionally have research responsibilities. A tenure eligible professor will have the title “Assistant Professor.”

Tenured professors at the College include any professor with the title “Associate Professor” or “Professor.” After their sixth year, an associate professor is eligible for full tenure and to be granted the title of “Professor.”

The data displayed and discussed in this article was gathered from OpenPayrolls and Glassdoor. OpenPayrolls is a publicly accessible website that annually requests payroll data from public universities across the nation. In order to access the data at a large scale, The Flat Hat used web scraping to acquire salaries from 2022-2024. Each professor subcategory was filtered by title, and professors with certain titles were excluded because it would result in unrepresentative data. Glassdoor’s data relies on voluntary submissions and was collected by hand.

In 2024, the median pay for a teaching professor was $61,921, which saw an increase of 3.61% compared to 2023. The standard deviation of salaries of teaching professors in 2024 was $15,193, the lowest of the three types of professors. This is due to the salaries following a tight spread, with the minimum salary received by a teaching professor being $45,900, and the highest being $120,936, leaving a difference of $75,036 between the two.

As for professors on the tenure track, the median salary in 2024 was $91,560, seeing an increase of 10.48% and 11.58% compared to 2023 and 2022, respectively. The standard deviation of tenure eligible salaries is second highest at $33,978, following a wider spread compared to that of the teaching professors. The minimum salary received by a tenure eligible professor in 2024 was $45,000, with the maximum being $267,597.

Lastly, for tenured professors in 2024, the median salary was $126,361, which saw an 8.25% increase compared to 2023 and a 10.58% increase compared to the 2022 school year. Tenured professors in 2024 have the highest standard deviation of all the professor types; $57,621 with the minimum salary received by a tenured professor was $71,400 with the highest being $467,246, leaving a difference of $395,846 between the two.

Time spent working at the College and additional titles are potential causes of this fluctuation. Professors can be first tenured as early as their third year and continue until retirement. Additionally, professors can hold additional administrative positions. For instance, Emeritus Professor of Classical Studies Dr. Michael Halleran, who formerly held the position of the “Provost” from 2009-2019, is currently the highest earning professor at the College. The comparison between the 2024 professor salaries, by title, can be seen below.

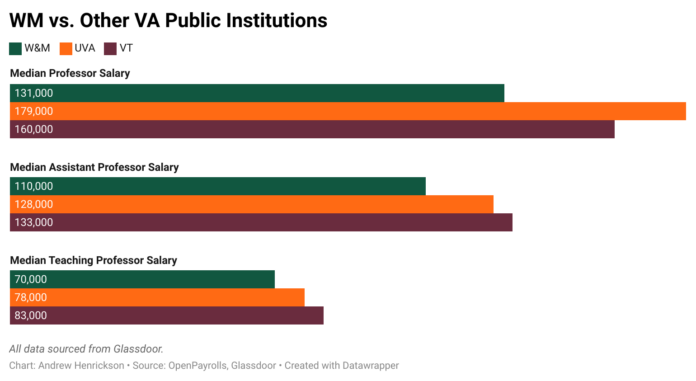

Compared to Virginia’s other research oriented public universities, the College pays significantly less in each of the three umbrella categories. For tenured professors, William and Mary pays 26.82% and 18.13% less than the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech, respectively. As for tenure eligible professors, William and Mary pays 14.26% and 17.29% less than UVA and Virginia Tech, respectively. This trend is lastly upheld in the pay of teaching professors across the three institutions, with the College paying 10.27% and 15.66% less compared to UVA and Virginia Tech, respectively.

However, economics professor David H. Feldman, whose research focuses on the economics of higher education and is the current president of the Faculty Assembly, pointed out that this may be an unfair comparison when looking at factors such as the size of school.

“William and Mary wishes that we are on the same level, but we are not,” he said.

Geology professor and department chair Christopher Bailey, who serves on the Faculty Assembly added that this data may be unrepresentative due to Virginia Tech’s engineering school and UVA’s medical school. Feldman said that it may be more accurate to compare the College to the institutions in the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia’s published peer group. SCHEV peer groups are formulated using enrollments, academic program offerings and degrees awarded, research funding and classifications created by higher education research.

In the past, SCHEV and the state government made a commitment to keep Virginia’s research oriented public universities in the 60th percentile of their peer group, which would mean that these schools would have higher salaries than at least 60% of comparable institutions, but now SCHEV has backed off of that goal.

“There is a reason why they do not want to talk about the 60th percentile anymore, because we [the College] have fallen to the bottom. Compared to our peer group, we are either last or next to last when they stopped calculating it [in 2017],” Feldman said. “They committed us to getting to the 60th percentile, but year after year after year we have fell and fell and when we got to the rock bottom, they [SCHEV] said we aren’t going to talk about the 60th percentile anymore.”

Feldman explained that this has been making hiring new professors difficult.

“If Clemson is offering $20,000 higher starting salary than we are, it is going to be hard to hire a junior economist away from Clemson. You are probably going to have a lower teaching load at Clemson. So you are going to have a lower teaching load, a higher salary, a larger department, so we lose,” Feldman said.

However, Feldman remarked that the College has been actively cognizant of the gap between its starting salaries and competing universities.

The College has the sixth lowest median salary compared to its peer institutions. Feldman cites reductions in state funding as a key cause of the College’s comparatively lower salaries.

“We were appropriating less money for higher ed, per student, in 2015 than we were in 1995,” Feldman said.

The College has had to adapt to this reduction in funding without compromising its quality of education, to avoid the “death spiral” given by reduced state funding. Alternatively, the college has begun to push more “levers,” charging higher tuition, facilitating more private fundraising and ultimately, spending less on professors.

A teaching professor, who opted to remain anonymous, shared challenges he has experienced in his position due to its heavy workload. He explained that the job search process for a professor is extremely difficult, with him specifically applying to around sixty positions and only getting back two; one from the College and one from a university in Turkey.

“They [the university in Turkey] were offering me way more, offering me housing even and a much higher salary,” he said. “They were only requiring me to teach one, maybe two classes a semester, where here I teach three classes every semester, so I definitely do a lot of teaching which makes it difficult to do any research.”

The teaching professor also described that the capacity of students they were teaching creates a difficult workload.

“One hundred ten students to keep track of with emails. When someone is sick, or has to miss something, I have to coordinate with them and help them make everything up, and that’s what takes a lot of energy,” he said.

Additionally, he mentioned that although professors have graders and TAs, which take care of homework and labs, a large majority of the work is still put onto the professor.

“Every year, [the College] keeps increasing the number of students in the classes too. I think a better solution would be to add more sections of the class, and hire more people to teach them rather than using the people we already have to do more, with not necessarily more pay,” he said.

This topic is not being entirely shoved under the rug however, with Bailey and Feldman starting a formal process to look at professor compensation at the college.

“We would like to talk about it again” Bailey said. “This is not meant to be a study that is aimed at ‘ha ha we told you so,’ but to collect the information and see where we stand — something informative.”