When Robert Gates ’65 decided he wanted to go to a college on the East Coast, his father was not happy with the decision.

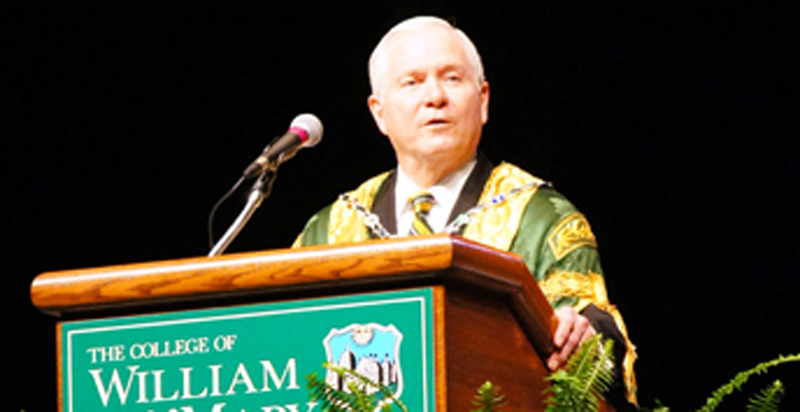

But the eventual 22nd secretary of the Department of Defense, 15th director of the CIA and 24th chancellor of the College of William and Mary ultimately won the argument and accepted his College scholarship, although it came at a cost.

“My father and I argued about it since the time I was 15, and I was 17 when I came here,” Gates said. “My brother is eight years older than I am, and he went to Kansas State University, so my father says ‘I’ll give you the same amount of money I gave your brother,’ which was $1,500 a year. So, I worked every semester I was here except for my very first semester.”

Besides working, Gates cut costs by serving as a dorm manager, promoted community service as president of the service fraternity Alpha Phi Omega, and served as business manager for the College Republicans, all while majoring in history.

Gates could tell he wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

“When I came here in 1961 from Kansas, everyone assumed I grew up on a farm, and they asked me if there was cattle rustling and stuff like that,” Gates said. “Having classes that were small enough, there was a real dialogue between the students and the faculty. You go to high school, and you grow up in a very narrow environment where pretty much everybody in your high school is just like you are. And high school, and you grow up in a very narrow environment where pretty much everybody in your high school is just like you are. And then you come to a place like William and Mary where there are people from all over the country and certainly now from all over the world. … It is a broadening experience.”

Although Gates received a D in freshman calculus, his study of history, which he continued at the doctoral level at Georgetown University, retained its value even within the federal back rooms of power.

“Civilization is not a civilization because of our technology,” Gates said. “It is because of languages and the arts, knowledge of our history. Frankly, I think, there are way too many in [Washington] and the media and elsewhere who don’t know anything about history, and it’s a danger. And part of the reason I knew it was time to leave was that I had to end up giving a history lesson every time I went into the situation room.”

The situation room was the setting for most of the new chancellor’s anecdotes. In initial interviews with former President George W. Bush, expectations for Gates were made clear.

“My priority was to turn the situation around in Iraq because we were in real trouble by the end of 2006,” Gates said. “I increased the size of the Army and Marines because I thought we were asking too much of the people already over there. … I wasn’t just at war with Iraq and Afghanistan, I was at war with Congress, I was at war with the White House, I was at war with the Department of Defense, I was at war with other agencies, in terms of turning this thing around.”

Since he retired from his secretary position in July 2011, Gates’ political stories will remain in his past, a fact that he willingly accepts.

“I think the time has come for the baton to be passed,” Gates said. “I think I realized it was time to quit when I realized that I was older than the last two presidents I have served, one by eight years and one by 20 years.”

Gates is the only defense secretary to serve under two presidents of different parties, and his perspectives in the situation room and elsewhere on Capitol Hill cast a hopeful but critical glance toward the future.

“People say, gosh how do you work for people as different as Bush and Obama, and I say well, you forget I worked for Carter and Reagan — you want to talk about really big differences,” Gates said. “I think partly the biggest difference was when I served them. I served President Bush in the last two years of his administration. … He knew he made his historical bed, so it was a different environment than in the first term. Obama, like any other president, wants to serve a second term. … Lots of issues get looked at through a political prism.”

In terms of foreign policy and engaging Americans in international political discourse, Gates called for change both in national leadership and the American frame of mind. He called Iran the U.S.’s most difficult security challenge he has seen in his 22 years in office.

“I think people talk about the situation in Iran a little too blithely, as if it is an intellectual problem,” Gates said. “Taking out those nuclear sites is an act of war, and if we think it is going to stop there … it’s completely unrealistic, and if Iraq and Afghanistan taught us anything, it was the inherent unpredictability of war.”

Gates laughed at the distance between Capitol Hill and his Seattle retirement home, which Gates and his wife, Becky, bought in 1993.

“It is as far away from the Hill as possible,” Gates said.

Admitting that during his time as a student, the College’s chancellor was considered little more than a ghost, Gates expressed hope he will return to campus once his book is completed in 2013. While the names of past College chancellors, such as Margaret Thatcher and Henry Kissinger, can be found in students’ history texts, Gates spoke of them with familiarity.

“I worked with and for the last three chancellors — Margaret Thatcher, Henry Kissinger, Sandra Day ’O Connor — and those were all worthy to be in the position,” Gates said.

Gates distinguished himself from these predecessors because of his experience with higher education administration; he served as president of Texas A&M University.

“I really enjoyed being the president of Texas A&M, and I look forward to the opportunity to re-establish a regular connection with both faculty and students,” Gates said. “What I told the various boards and College President Taylor Reveley and the Rector is to the degree that I can be helpful on the development side, I’m willing to do that.”