A study by Duke University indicates that movies tend to confuse students when it comes to historical accuracy. In short, blockbusters like “Titanic” and “Glory” are bad news when it comes to learning about the past. Stay away, the researchers warn.

Sorry, but these are exactly the kind of people who deserve to be clonked on the head with a history textbook. Calm down.

By its very nature, history is skewed. For those who forget, the past is essentially a story, and, like all stories, its presentation depends on the storyteller. If James Cameron wants to detail the ill-fated voyage of the Unsinkable Ship through the eyes of star-crossed lovers, then so be it. Whether Jack and Rose actually existed isn’t what’s important. The big idea, in this case class conflict in the early twentieth century, matters much more.

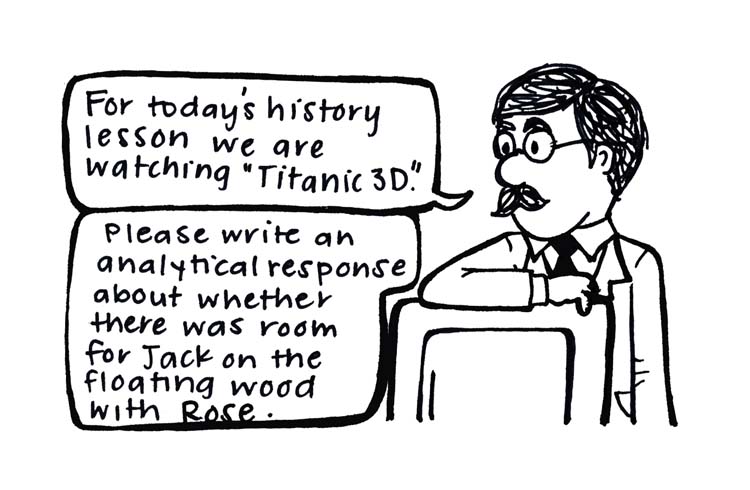

Nowadays, most history classes have moved away from the tiny details. After all, how often do your professors ask you to memorize dates? The current discussion tends to emphasize analysis, the how and the why: What caused what, and what were the consequences? Likewise, it seems that today’s preferred historical method exalts the institution above the individual, the combined actions of a group over those of one person. No professor cares whether Officer Murdoch sent a bullet through his brain, as the film depicts, or died in the water — the truth according to survivor accounts. If he does, he needs to get his priorities straight.

So when does it matter? Hardly ever. Maybe if you’re writing a book on the subject. Or giving a tour of a museum exhibit. Or claiming expertise. Even history majors probably don’t need to concern themselves with Mozart’s personality (a controversy raised by his characterization in “Amadeus,” one of the films used in the study). These people hopefully have the sense to recognize that Hollywood’s portrayal is just that: One portrayal, which doesn’t necessarily provide the whole story. Students aren’t stupid. Most recognize the questionable nature of period pieces. If accuracy truly matters to them, then they will check other sources. If it doesn’t, life goes on.

Riddled with error or not, films have their merit. They pique interest, often about subjects you would have otherwise overlooked. Take “Glory,” one of the films used in the study, for instance: I’ve never come across a textbook that mentions the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, but the film reminds us that the Union’s first black regiment was a big deal. And what about “Newsies”? Most history classes tend to skip over the Newsboys Strike of 1899, but the Disney musical has turned this lesser-known event into household knowledge. We don’t get all the facts, but at least we’re aware, and, if we so choose, we can pursue the subject to gain a better understanding of it. That’s when bookstores come in: They have mountains of books that deal with the historical events popularized by hit films.

To those who see red when the screen doesn’t match the printed page, keep in mind that Hollywood isn’t out to replace your cherished textbook. Movies are meant to entertain; leave the instruction to others.