When the Dalai Lama was exiled from Tibet by the Chinese in 1959, he found a sympathetic audience in much of the Western world. Now, more than 50 years later, he is responding to a much more specific demographic: college students. Tomorrow, en route from Syracuse University to the University of Virginia, the Dalai Lama will spend the afternoon at the College of William and Mary speaking about human compassion.

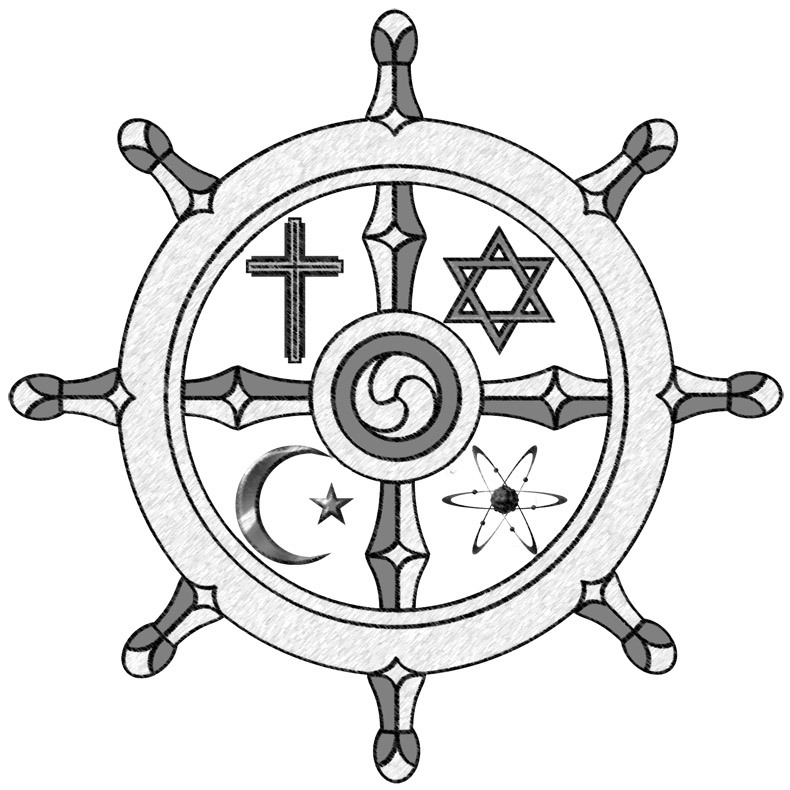

Unlike at his home in Tibet, the Dalai Lama — leader of one of four orders of Tibetan Buddhism — is unlikely to find Kaplan Arena teeming with young Buddhists. Instead, he will find a group of students who come from a variety of religious backgrounds and philosophical perspectives. Despite obvious ideological differences, members of the College community do not seem to feel the need to bridge the gap. For many, the Dalai Lama’s message is universal.

“To me, the biggest part of Buddhism is the fact that it’s a lifestyle more than it’s a religion,” Mohamed Aboulatta ’13, president of the Muslim Student Association, said. “It’s just supposed to govern the way you live, and it’s peaceful. It’s immaterial, and it’s trying to get away from the stresses and objects of this world that weigh you down.”

From Aboulatta’s perspective, the purpose of the Dalai Lama’s visit is not to undermine anyone’s religious ideals, but rather to enhance them.

“It’s not trying to supplant your religion; it’s just trying to teach you ways to cope with things in life,” he said. “That’s what’s so great about Buddhism. It’s a thought process. It is putting away the heavier and the darker things in life to better enable you to be more spiritual in your own religion and in life in general.”

Max Blalock, campus minister of the Wesley Foundation at the College holds a similar view. For Blalock, the Dalai Lama’s principles back up the Christian ideals he already values.

“The goal of Buddhism, which I don’t think is very different in general conceptual terms from the goal of lots of our faiths — whether it’s Judaism, whether it’s Islam, whether it’s Christianity — is that we’re able to, to use a Christian term, take the scales away from our eyes … and to be able to see the world truly as it is,” he said.

Blalock’s idea refers to the Buddhist theory of emptiness, which is related to the idea that exists wholly independently of other things. From this principle, known as dependent arising, Buddhists reason that because humans are not autonomous beings but rather are dependent on one another, it is essential to have compassion for other people. Emptiness and compassion are the two main tenets of the Dalai Lama’s teaching, according to Kevin Vose, the Walter G. Mason associate professor of religious studies.

Vose, who specializes in Tibetan Buddhism, spoke last Thursday about the Dalai Lama’s life and the greater political history surrounding his exile from Tibet to provide students with background knowledge in preparation for his upcoming visit. Vose believes the Buddhist principle of compassion is the common denominator among all religions.

“Compassion, [the Dalai Lama] says, is the root of all religion and it’s the one thing that all religions have in common,” Vose said. “All religions try to produce compassionate people.”

For students who would otherwise dismiss the Dalai Lama, Vose stresses the effect of not only his words, but also his presence on the true understanding of the concept of compassion.

“Meeting him, hearing him talk in person, you really come to process the teaching of compassion,” he said. “The need to help other people really hits home when you see how he conducts his own life.”

Visiting instructor of religious studies Wamae Muriuki echoed this idea. Muriuki’s specialty is Japanese Buddhism, which is distinct from Tibetan Buddhism and has its own sects and leaders. While the Dalai Lama is not associated with Japanese Buddhism, he is viewed in Japan as he is in the West, as a religious figure whose message is not specific to single religion.

“I think he … hits upon universal themes, like the need for compassion, to treat one another with love and kindness —about the importance of wisdom and to nurture wisdom and to approach the world and each other with wisdom,” Muriuki said.

Muriuki also pointed out that the Dalai Lama is one of the most forthcoming modern religious leaders with regard to the reconciliation of religion and science.

“He’s sort of leading the charge on the conversation between religion and science — not only looking at the scientific benefits or basis of meditation, but also he’s taken the lead in saying that if there are any Buddhist teachings that don’t accord with science, then perhaps Buddhism should discard those teachings,” he said.

Students who are well-versed in religion or science may naturally be interested in hearing what the Dalai Lama adds to the academic discussion. For those with less of a background in these fields, the merit of the Dalai Lama’s visit lies in gaining exposure to new methods of thinking, according to Thomas Mattessich ’14, president of the Philosophy Club at the College.

“I’m just hoping to hear someone speak who has something to say that is different from my perspective,” he said.

The idea of gaining a new perspective seems to resonate particularly well at the College where, according to Vose, all students stand to gain important knowledge from the Dalai Lama’s talk.

“I think that his basic message is a very powerful one about the need to make connections with other human beings,” he said. “Specifically, I think, for a place like [the College] where we have a very large crowd of very bright, talented young people, that his message is to say that we owe it to each other to make the best of what we have, and here we have a lot. We all have very sharp minds, talent, [and the] ability to sort of think about what we owe to other human beings as far as what we choose to do with our lives — that’s a good thing for our college to hear.”