In Williamsburg, 238 people — the approximate number of students living in DuPont Hall — identify themselves as homeless. This census data figure from 2008 demonstrates the lack of affordable housing in the area.

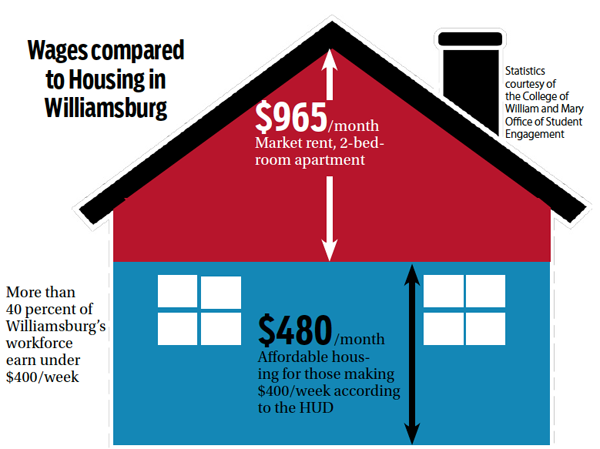

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable housing as lodging that costs less than 30 percent of a family’s income. November 2011 statistics from Campus Kitchen reported 40 percent of Williamsburg’s workforce earns less than $400 a week. In order for their housing to be considered affordable by HUD, these residents should pay about $480 a month for housing. However, the average rent in Williamsburg is $1,007 a month, over twice the HUD prescribed amount.

“[Williamsburg’s] industries are mainly hospitality and tourism, which are very seasonal and not permanent and may be part-time and very low-wage,” senator Danielle Waltrip ’14 said. “That’s the main source [of income], plus the College. And the College also has a lot of low-paid jobs.”

For years, students have complained about expensive off-campus housing issues, including the three-person rule that forbids renters from allowing three nonrelated people to live in the same house, a policy currently under review. Additionally, the density cap has limited the number of people who can live in a certain area but was recently eliminated in certain areas of the city.

City Outreach Coordinator Roy Gerardi does not think changing these rules will get to the heart of the problem. People who are homeless usually possess other underlying issues like substance abuse or anger management.

“We try to find out what are some of those underlying factors then bring along professional help,” Gerardi said. “The best thing students can do is volunteer. Most of the kids I encounter don’t have any positive role models, male role models in particular.”

Still, poverty plays a much greater role in Williamsburg than in surrounding communities. 20.3 percent of people live below the poverty threshold, according to Campus Kitchen. In James City County, that number rests at 7 percent.

“This isn’t uncommon in college towns, for instance, because demand drives up cost and in Williamsburg, the demand for student housing and the demand for other housing is high, which means that the cost goes higher,” CEO of United Way of Greater Williamsburg Sharon Gibson-Ellis said. “I think Greater Williamsburg could do a better job at understanding why it’s important for us to embrace those who serve us who want to live among us. What is it that we can do to ensure that they can live among us?”

City Director of the Department of Human Services Peter Walentisch, who has worked with about 500 people who are homeless in the last two years, says that Williamsburg faces the same problems that every city does, especially coming out of the recession.

“Williamsburg has a higher standard of living,” Walentisch said. “You always have a population that’s commuting into the area. But that’s the case everywhere. You look at any city in the country — Charlottesville, I’m sure, has some of the same issues. You have people commuting into Charlottesville who might not be able to afford to live in the [city] limits.”

The City of Williamsburg worked with organizations like Campus Kitchens, United Way, Avalon and the Salvation Army to run a scattered-site model shelter system, incorporating motel rooms, transition housing and public housing to provide shelter for the homeless.

“This area is built on partnerships,” Walentisch said. “In the Historic Triangle, people who do human services and social services and community services are partners with each other in major ways. … The churches have organized ecumenically in order to address some of the social needs of individuals and families here. They’ve done an outstanding job rallying to the cause. It’s that kind of thing that the area thrives on.”

Local churches have teamed up to provide shelter to the homeless for one week each this year from November through March. Last year, the City Government provided a bus to take residents to a similar Newport News-based program.

“What typically happens is in the winter months, hours get cut from forty to sometimes fifteen hours a week,” Gibson-Ellis said. “That’s when [workers] fall into crisis and can’t pay their rent.”

Now through Feb. 23, the Student Assembly is hosting a clothing and goods drive in the Sadler center. Students can contribute basic necessities like toothbrushes, floss and sunscreen in addition to items such as extra clothing and boxed food. These items will be donated to a shelter in Newport News.

Students can also volunteer in the upcoming Hands Together Historic Triangle, a one-day event that provides services, such as haircuts, to community members.

“We are all, to some extent, leaders within the community,” Secretary of Student Life Alicia Moore ’14 said. “This is our home. I feel like it’s my duty, as a leader, as a student and as another human being, not just to look after the well being of others but to help create a system where these disparities don’t occur to the extent at which they do.”