I still remember when a chemistry teacher in high school told the class that English majors will probably never make any money, and I was quick to pin her as the sole fault of modern education. Since then I have heard plenty of back and forth between advocates of a science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education and advocates of a full humanities education.

GERs remind us that the College of William and Mary is a liberal arts college, but the significance of a liberal arts education is that students can take whatever courses they want. Students should not be required to take specific courses simply because a certain camp of thinkers values certain skills over others. The College should limit GERs so that they can be completed during students’ freshman year, allowing students to devote the remaining years entirely to their selected majors.

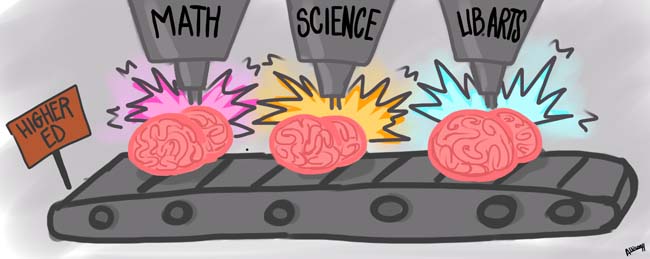

A recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education suggested that college students do not use enough quantitative reasoning skills in class. Obviously, STEM majors are exempt from this article’s observations. This article seems to be advocating for an across-the-board STEM education for college students.

STEM advocates often exaggerate the importance of quantitative reasoning. I believe that quantitative reasoning skills are necessary for advancements in technology, medicine and engineering but that is where their real relevance stops. Some people try to make a case that numbers matter in the daily activities of everyone, regardless of their careers. I agree that I use basic arithmetic every day, but will I really use calculus in every possible career that I might choose? Doubtful.

I do not mean to discredit education in STEM fields, but classes that stress quantitative reasoning fit some students better than others. Upon reaching college, students should know whether they are more fit for quantitative or qualitative reasoning.

If I know that I want to write books for the rest of my life, then I should stock up on English courses. If I know that I want to sell books for the rest of my life, then I should take business, statistics and calculus courses. Students are responsible for gaining knowledge necessary for their prospective futures.

Required courses have a place, but that place is in compulsory public education, not higher education. Public education’s purpose is to give students an idea of each of the subjects so that they can sharpen specific skills in college. After all, college is a financial investment. Students put money in with the expectation that they will get money out in their future careers. It only makes sense that the courses a student pays for in college are relevant to the career that they hope to have.

I do not have a problem with taking GERs and survey courses as a freshman, as it is beneficial to experience a variety of subjects. However, if I decide to major in English, I shouldn’t be using quantitative reasoning skills in my courses by the time I’m an upperclassman. Likewise, liberal arts colleges shouldn’t insist on shoving English down the throats of STEM majors.

What needs to change is the way that these varied subjects are taught in middle and high school. Eventually students stop using what they learn in their daily lives and wonder, “When will I ever need to know this?” They raise a valid question that secondary education often fails to answer. More emphasis should be placed on realistic applications of the skills students are learning.

Colleges are certainly doing us a favor by requiring a broad range of courses in the first year and calling it a liberal arts education, but the emphasis on liberal arts needs to come earlier. Instead of students excelling at specific courses in high school and then spending money on survey courses in college, education should be the other way around.

Email Stuart Mapes at smmapes@email.wm.edu.