The College of William and Mary is officially boycotting a boycott.

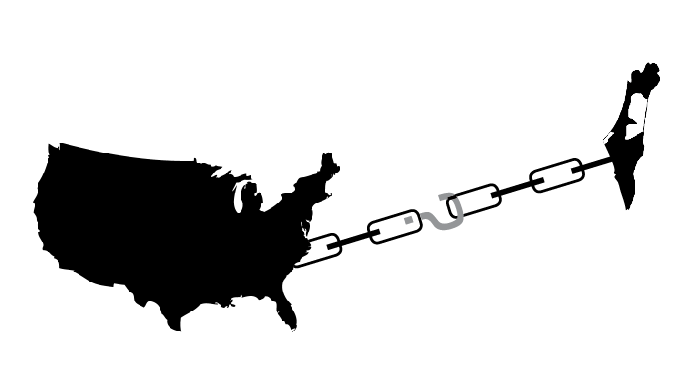

In December 2013, the American Studies Association voted to boycott Israeli academic institutions, responding to pressure from Palestinian civil societies. Much of the Palestinian community has been urging organizations since 2005 to denounce Israel for violations of Palestinian students’ rights. Following the ASA’s announcement of the boycott, a large and growing number of U.S. universities, including the College of William and Mary, spearheaded a wave of opposition.

College President Taylor Reveley and Provost Michael Halleran released a statement rejecting the boycott Jan. 3, claiming, “Colleges and universities need to engage one another to expand the frontiers of human understanding, not shun one another.”

“The American Studies Association is a relatively small body, but the position they took was so — in our view — inimical to the basic tenants of academic freedom, free exchange of ideas, that it seemed important to make clear that we rejected their resolution,” Halleran said.

In opposing the boycott, the College is in good company: George Mason University, University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia Tech join the College on the list of Virginia universities to formally reject the ASA’s resolution.

Within the ASA, 66.05 percent of members voted in favor of the boycott, while 30.5 percent opposed it and 3.43 percent abstained.

In the official statement on its website, the ASA describes the boycott as “a refusal on the part of the ASA in its official capacities to enter into formal collaborations with Israeli academic institutions, or with scholars who are expressly serving as representatives or ambassadors of those institutions (such as deans, rectors, presidents and others), or on behalf of the Israeli government, until Israel ceases to violate human rights and international law.”

Arguments for the rejection of the boycott vary among critics. Many people see the boycott as counterproductive toward general educational goals. Tamara Sonn, religious studies professor at the College, acknowledges that Israeli academic institutions have violated Palestinian civil rights, but she argues that a boycott is the wrong path to take to promote change.

“I would rather see efforts to establish solidarity among university students and faculty in support of compliance with international law and global human rights, including Palestinians,” she said.

For others, however, the issue is much more personal. Jenna Milstein ’16 and her family have strong connections with Israel. She defends the country, which has historically been a target of widespread violence. Clearly, Palestinians are not the only ones who feel as though their rights are being endangered.

“There’s no other country in the world that is under daily terrorist attacks from multiple terrorist organizations on all of its borders and all sides, and no one says anything except for ‘Attack it,’ which makes no sense to me,” Milstein said.

Milstein commends the College on its rejection of the boycott, not only because of her own feelings about Israel, but also because she believes that, by instituting the boycott, the ASA is defeating its own purpose.

“I think the American Studies Association has its place, and its purpose is to … talk about American Studies, essentially, and to enhance those freedoms of discussion about issues, and to me this is kind of the opposite of that,” Milstein said.

Although many believe the ASA’s boycott is counterproductive, it may even go beyond that: The boycott may be illegal. Because it targets people from a certain national origin, many classify it as unlawful discrimination. The ASA is currently facing the possibility of multiple lawsuits on these grounds.

Although backlash against the boycott has been strong, there is also general agreement that any effects it may have will be limited. One reason for this is that a boycott that involves so many people on opposite sides of the world will be difficult — and likely impossible — to enforce. Another claim is that the ASA is not powerful enough on a global scale to foster change; at best, the boycott is symbolic.

“Some institutions have power,” Halleran said. “Others can lend a moral voice. … As a body, they were making their views heard. If it will have any impact at all other than a probably undesired impact of having over a hundred universities reject it, I don’t think it has influence, except as a moral statement — not as a practical matter.”