It is difficult to find a college student who is not worried about the debt they will face following graduation. With the cost of higher education increasing every year, the fact that two-thirds of students from across the country graduate with some level of debt is not surprising.

According to a study conducted by The Institute for College Access and Success in 2013, the average borrower owed $26,600 upon graduation, and the amount has only increased since then. In 2013, Virginia had fewer students graduating with debt than the national average, at 59 percent — still more than half of Virginia students.

In an extreme example of the swiftly-rising costs of higher education, the University of Virginia announced in late March that tuition prices for incoming in-state students will be increased by 11 percent in the coming fall. Current students will only face a 3.6 percent increase, which, while still a sizeable increase in tuition, is more aligned with typical increases in U.Va. tuition.

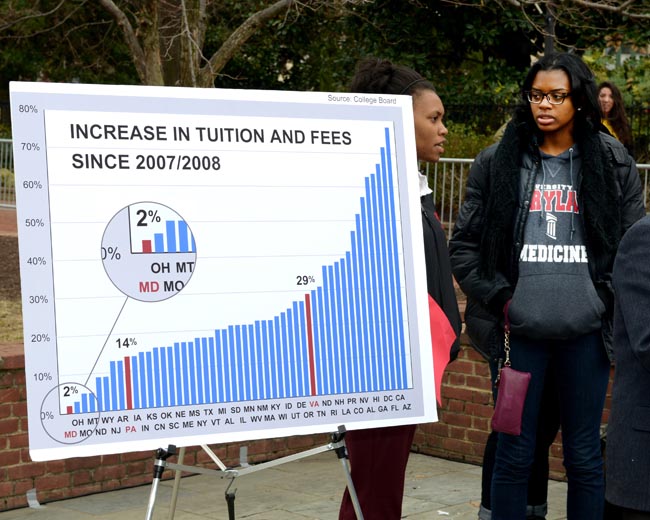

Data from both the College and U.Va. show that tuition prices have, for the most part, been increasing since at least 2001. These increases have been rather dramatic.

A freshman entering the College in the fall of 2001 would have paid $4,604 in tuition, whereas a freshman entering in the fall of 2015 will be paying $13,978 in tuition. This increase amounts to over $9,000 in 14 years, not including inflation.

Calculating inflation using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI Inflation Calculator reveals that $4,604 in 2001 translates to $6,101.98 in 2015. This is vastly different from the current tuition rate. When adjustments for inflation are made, there has still been an almost $8,000 increase in undergraduate in-state tuition at the College since 2001.

The extent of this increase is somewhat astounding and unquestionably unacceptable.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income in Virginia in 2000 was $50,069 and in 2013 it was $62,666. This means that in 2001, in-state tuition at the College was approximately nine percent of the average Virginian household income. In 2015, in-state tuition will be approximately 22 percent of the average Virginian household income. This data is troubling because it shows how attending even an in-state, public university is becoming an unaffordable option for the average American family.

In 2013, the College adopted “the William and Mary promise,” which guarantees to new students that their tuition will not increase from the price they pay their first year. This promise is a step in the right direction for current students, but it does not protect prospective students from significant tuition hikes, like the one incoming freshmen at U.Va. now face.

Today’s students are caught in an impossible position, as more and more job postings demand bachelor’s degrees at a minimum while tuition prices skyrocket. When students see attending college as their sole option for success, while knowing attending college will cost a significant portion of their family’s income, they are often forced to decide between their family’s current financial stability and their own future.

Of course, there are grants, scholarships and loans available for students who are unable to afford the immense costs of attending college. However, grants and scholarships — in other words, “free money” that doesn’t have to be paid back — are often hard to come by for students in the middle class.

The majority of college students fall into a bracket where the government considers their families well off enough to not qualify for grants and scholarships, but who are still unable to actually afford the costs of college today.

Attending an in-state, public school should be an affordable way to get a higher education. Yes, college degrees are more in demand than ever but that does not mean drastically rising tuition prices need to be crippling the middle class. Just because colleges can raise their tuition doesn’t mean they should.

Email Emily Chaumont at emchaumont@email.wm.edu.