Recently the National Collegiate Athletic Association has come under fire for its handling of academic requirements as well as its treatment of collegiate student-athletes. William and Mary is a mid-major school in Division I, and, while usually far from news of scandals and violations, was the center of controversy 65 years ago. In 1951, the football program fell under fire for allegedly manipulating transcripts and grades during a time of emphasis on athletics at the College, leading to several prominent employees resigning.

The infamous scandal of 1951 became known to the public in August of that year, right before students were coming back to campus. Despite gaining public attention at that time, the allegations can be traced to a few years prior and were subjected to several internal investigations before the news broke to the local press.

During the early days of NCAA membership, the Tribe — at that time known as the Indians — was pouring resources into growing a large football program, bolstered by a secretive resolution passed by the Board of Visitors in 1946.

“The Board adopts as its athletic policy a program that would produce athletic teams that could compete successfully with other teams in the State of Virginia belonging to the Southern Conference and to such extent as it could be reasonably expected that the College teams would win more games than they lost,” the BOV minutes from Oct. 12, 1946 said.

This resolution remained an only need-to-know policy until everything fell apart in 1951. The athletics surge likely stemmed from an increase in male students after the end of World War II in 1945. Students at first were skeptical of the apparent emphasis on athletics. In 1944, 8 a.m. classes had been added to the schedule to accomodate afternoon football practices.

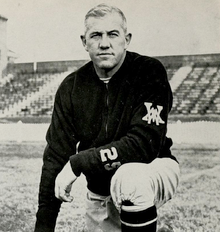

From 1946-1950, head coach Rube McCray was in charge of both the football team as well and served as the Athletics Director for the school and as a faculty member for the now-defunct Department of Physical Education. The team had a combined record of 34-17-2 in the five seasons before the scandal broke, making appearances in the 1948 Dixie Bowl and the 1949 Delta Bowl and winning the Southern Conference in 1947. Despite a 4-7, 3-3 SoCon record in 1950, this era remains part of the most successful era of football at the College. However, that legacy was tainted by allegations of McCray and former basketball head coach Barney Wilson tampering with high school transcripts and awarding unearned credit to keep players eligible.

The recent administration of our intercollegiate athletic program is dishonest, unethical, and seriously lacking in responsibility to the standards of William and Mary … I am puzzled at the realization that to resign is not to accomplish anything … it seems to constitute forfeiting the hope of so doing.” — Former Dean of the College Nelson Marshall

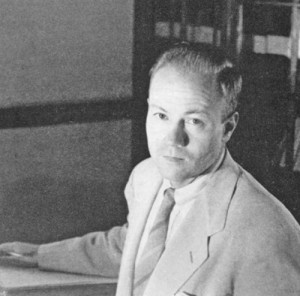

As many scandals start, it began with rumors. Former Dean of the College and member of the athletics committee Nelson Marshall had been approached by a mix of faculty and students at the College with complaints concerning the rumors, so he began to investigate. This was in 1949. Marshall submitted his resignation to College President John Pomfret in a letter expressing concern for the school as he began to search for the truth April 20, 1951.

“The recent administration of our intercollegiate athletic program is dishonest, unethical, and seriously lacking in responsibility to the standards of William and Mary,” he said in his letter. “I am puzzled at the realization that to resign is not to accomplish anything … it seems to constitute forfeiting the hope of so doing.”

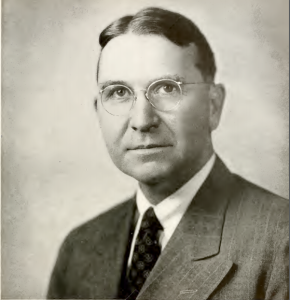

Although Marshall was resigning, he remained in the area to aid in investigating the mysterious events. The scandal itself was a pressure cooker about to burst in the following months. In the mid-1900s, the College had a men’s physical education major, which was the principle major for student-athletes, especially football players, who wanted a degree while trying to enter the National Football League. With McCray as the head coach, athletics director and department of physical education chairman, it was an inevitable disaster. In late June, correspondence between Pomfret and Marshall shows evidence of a private meeting to talk about the rumors. July 3, 1951, the faculty of the College held an emergency meeting to form an investigative committee made up of five staff members and to establish a media blackout by the faculty for anyone except Pomfret. The committee, chaired by Richard Morton, set out to make an official report for Pomfret to present to the BOV. The report, titled “Report of the President to Board of Visitors relating to academic malpractices in the Department of Physical Education,” was published Aug. 15, 1951. However, a great deal happened in the month between.

According to the Report, on the same afternoon as the committee’s formation, Pomfret wrote to McCray to answer the committee in its investigation.

“I stated also that if [McCray] felt that he could not defend his conduct in these matters it was my personal belief that he should give serious though to resigning his position at the College,” Pomfret said in the Report.

If McCray had not resigned, as he did July 7, he would have had to defend himself in a more serious sequence of hearings and likely bring an NCAA response down on the College. One of Morton’s manuscripts about the events showed that the resignation was not even Pomfret’s idea, but rather that of concerned alumni who wanted to avoid investigation and met with Pomfret.

“Mr. Pomfret thus informed the committee that Mr. Hoffman, accompanied by several influential Norfolk alumni, [met] him on the afternoon of July 3,” Morton said in his writings. “These gentlemen [proposed] that the College accept the following solution to the McCray case: That Mr. McCray be permitted to resign from his position, the resignation not to take effect until after the 1951 football season.”

“Mr. Pomfret thus informed the committee that Mr. Hoffman, accompanied by several influential Norfolk alumni, [met] him on the afternoon of July 3. These gentlemen [proposed] that the College accept the following solution to the McCray case: That Mr. McCray be permitted to resign from his position, the resignation not to take effect until after the 1951 football season.” — Special Committee of the Faculty Chairman Richard Morton

These mysterious “influential alumni” are not mentioned again in Morton’s manuscripts, but the effects they had are mentioned throughout the archived files on the scandal, as McCray did end up resigning, which did not give the College any real power to indict him for any allegations later.

Heading back to the Report itself, two cases were established of alleged malpractice, inspired by Marshall’s concerns. The first was of unearned credit given to students during summer sessions in 1949 and 1950, the period of interest for the committee. Earned credits were listed on college transcripts despite the students, members of the football team, having not actually been on campus for more than a few days in the summer.

“At a meeting of Administrative Offices with Mr. McCray and Mr. Wilson June 26, Mr. McCray admitted that several of these students were not in residence,” the report states.

McCray provided some insight into the problems right before the committee formed, providing a basis for the first case. The second case relates to tampering in admissions by altering high school transcripts, which McCray denied in the June 26 meeting. He was asked about it because student-athlete transcripts went through the department of physical education prior to the scandal. Some proof was discovered in late July by the committee of this ethics breach, accompanying supplemental information about Wilson’s mishandling of funds for jobs for athletes, a smaller third case.

“On July 29 also evidence was presented indicated that four women secretaries had said that they had knowledge of the altering of high school records by Mr. McCray,” the report said.

McCray and Wilson’s resignation letters were sent in July 7, although Pomfret did not accept them until Aug. 13, three days after official letters of resignation were received. July 7, 1951 marked an important day for the investigation, as the committee, upon receiving news of the resignations before they were made public, decided not to pursue the allegations, although the matter was not settled. Additionally, Pomfret met with the faculty that day to give news of the coaches’ departures.

“The two men charged with academic malpractice will sever their connection with the College through resignation after a reasonable period permitting them to seek other positions,” Pomfret said in the report.

The committee wished to continue investigations since there was no closure to the problem, only avoidance. Due to apparent pressure from the BOV, Pomfret, Morton and the other faculty were limited in their ability to reprimand McCray and Wilson further. Pomfret expressed an official version of the story in the report.

“Since the Special Committee of the Faculty was not called upon to hear Mr. McCray and Mr. Wilson, the College cannot prove or disprove seriatim the allegations made on July 11 or the supplementary allegations,” Pomfret wrote. “There is ample precedent for tempering justice with mercy.”

The July 11 date referred to is in agreement with the College’s disclosure of news to the press, which was only writing articles based on rumor at the time, and how William and Mary would limit its interaction with media concerning the scandal.

The findings of the report mention seven students listed as having unearned credit, while the committee could not obtain all of the falsified high school transcripts due to limitations of the search.

The day after the report came out, the BOV resolved that the committee examine the gathered evidence for a more in-depth report. Morton’s committee completed that report by Sept. 12, 1951. Pomfret resigned the next day, as his administration was condemned on Sept. 8 for not promptly responding to the rumors.

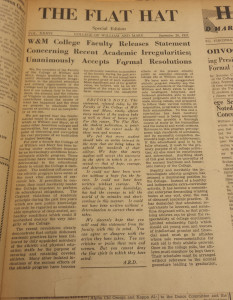

We are agreed that the fundamental cause is an athletic policy which at William and Mary, as at many other American colleges and universities, has proceeded to the point of obscuring and corrupting the real purposes of an institution of higher learning,” — Faculty statement in the Sept. 21, 1951 special edition issue of The Flat Hat

By this time, the fall 1951 semester and football season were underway, as well as the BOV’s search for a new president. The Flat Hat released a special edition issue Sept. 21, 1951 containing a faculty statement on the academic irregularity.

“We are agreed that the fundamental cause is an athletic policy which at William and Mary, as at many other American colleges and universities, has proceeded to the point of obscuring and corrupting the real purposes of an institution of higher learning,” the statement said.

The faculty statement denounced the current program, citing concerns that varsity athletes could not pursue anything except physical education majors and that the athletic emphasis was taking away from the core mission of William and Mary as an institute of higher education. The Flat Hat’s publication of the statement was signed by all 90 faculty members, including Marshall and Morton, and resolved to make changes including the establishment of separate committees on admissions, athletics, scholarships and student aid as well as academic status, elected from and by faculty.

While the faculty was making amends and trying to bring athletics down a peg, the student response to the faculty’s actions was mixed, according to the results of a poll published in The Flat Hat October 9, 1951.

“I do not think we will gain anything through de-emphasis of athletics,” respondent Fred Allen said. “I know of no better tie between alumni and their alma mater than good athletic teams.”

Others supported the ideas behind the faculty statement.

“I support entirely the manifesto of the faculty, because it is forthright and stern,” respondent Richard Hutchenson said. “Every college should have a well integrated physical education program, but professionalism insures both the college which promotes it and those who must participate in it.”

Meanwhile, alumni were on board to report on the matter while the search for a new president still was underway. In Oct. 1951, The Alumni Gazette published the first of three planned editorials about the football program from 1939-1951. Written by editor Charles McCurdy ’33, the article tries to explain some of the incident to alumni.

“Before the bombshell broke the usual summer calm, many persons seriously interested in the welfare of the College, including administrative officers, members of the faculty, alumni and students, had begun to question the extent to which athletics, particularly football, had become powerfully absorbing in practically every center of the College,” McCurdy wrote.

The second and third editorials never printed, the BOV jumping on the Alumni Society Board of Directors to censor the pieces, leaving McCurdy and much of his staff no choice but to resign. The articles still have not been published.

As the semester got underway, acting President James Miller held the reigns, but was replaced by President Alvin Chandler, whose inauguration was the front page of the Oct. 16, 1951 issue of The Flat Hat. Miller praised Marshall’s efforts in exposing the scandal, as seen in the Sept. 29, 1951 Newport News Daily Press in an article by Lloyd Haynes Williams.

“[Marshall] did what few men in the world would have had the courage to do,” Miller said to Haynes Williams.

Confronted with [the investigation] the College’s Board 1) accepted the resignations of the two responsible coaches, 2) reaffirmed rather than revised the athletic policy, and 3) blamed the President and thus claimed the fault was one of administration rather than policy.” — Dean Marshall

In the aftermath, Chandler took over in a quick transition, allegedly in a decision rushed by the BOV to get over the bad publicity and avoid a large hit to the College’s reputation. Marshall resigned fully after the appointment, explaining his reasoning in his “1951 Christmas season letter to all friends.”

“Confronted with [the investigation] the College’s Board 1) accepted the resignations of the two responsible coaches, 2) reaffirmed rather than revised the athletic policy, and 3) blamed the President and thus claimed the fault was one of administration rather than policy,” Marshall wrote in his letter.

Marshall was not wrong, as the censorship of The Alumni Gazette and the suspicious handling of the resignations that tied the hands of the special committee show more of an effort of covering up and getting past the whole thing rather than fixing it. The main change was the faculty committees as well as the separation of the physical education department from athletics. Marshall criticized the new administration further in his letter.

“This Board turned on the Faculty with a surprise presidential appointment,” he wrote. “It was clearly an anti-Faculty appointment, an administration to which [I] could not be loyal.”

Further examination proved impossible, as most of the administrative members are deceased, Pomfret passing in 1981 and McCray in 1972.

Head coach Marvin Bass took over Indians football the next year, which posted a 7-3, 5-1 SoCon record in his first of just two seasons he held the position. Chandler held the presidency for 10 years.

The scandal remains an important example of almost a century of American higher education battling for superiority with varsity athletics, as colleges and universities across the nation split resources between the ever-growing NCAA sports and staying true to the academics that higher education was made for. As a result of that tradeoff reaching a breaking point in 1951, William and Mary is no longer a football powerhouse in its current state, holding middling records and perennially making the playoffs for the NCAA’s Division I-AA, instead aligning its priorities more toward academics while keeping athletic tradition alive with less emphasis.

Author’s note: Special thanks to the Earl Gregg Swem Library’s Special Collections Research Center for providing the archived resources used in this article.

Not really what the article is about, but the last paragraph did not sit well with me. The statement that Tribe football now is “holding middling records and perennially making the playoffs for the NCAA’s Division I-AA, instead aligning its priorities more toward academics while keeping athletic tradition alive with less emphasis” is a contradiction. First, middling would imply average and making it to the NCAA 1-AA football tournament while playing in the toughest conference in NCAA 1-AA football while consistantly getting ranked nationally does not sound average to me. Second, as a former student athlete, current parent of a student athlete and friend of some current coaches at WM, I wouldn’t say athletic tradition gets less emphasis now. This is the Tribe – we have student athletes in place with the ability to excel in the classroom and in athletics and they have dedicated coaches that are also committed to excellence in both arenas.

Someone pull the stick out of Tribemom’s ass. Another excellent article composed by the ever-exceptional Nickle Sippyla. Should I be studying for one of my three tests this week? Or perhaps working on that 8 page paper I have due on Thursday? The answer is probably yes, and yet here I am, compelled by this amazing piece of journalism. Like an old woman peering eagerly through the thick lenses of her spectacles at the newest episode of “Days of Our Lives”, I find myself unable to resist tearing through this delicious list of scandalous escapades (sexual and otherwise). Carrie Washington herself would be proud, as would George Washington, and even (dare I say it?) Denzel himself. With this article, the bearded journalist with the mostalist proves once again that he is the King of Sports. Also, does anyone else think that photo of former President John Pomfret looks suspiciously like Arnold Ernst Toht (The Nazi with the glasses from Raiders of the Lost Ark)? I’ll let you come to your own conclusions, I just wanted to put the similarity out there… Also, the Head Coach from 1951 had a sweet name. “Rube McCray”. Say it again, out loud. It sounds like melted butter running over your tongue, sweet syrup dripping down your lips and onto a stack of warm and fluffy pancakes. “Rube McCray”. The world needs more Rubes. It’s a name that has wrongly fallen out of fashion. Maybe I’ll name by son Rube someday. Or daughter, I’m not going to pretend to give a fuck, it works either way! Rube Beejay. I like the sound of that, yeah, it’s gotta ring to it, donnit? Shh, Tribemom’s only gone for the moment…

Now hush little Rube don’t you cry

Everything’s gonna be alright

Stiffen that upper lip up little Rube, I told ya

Daddy’s here to hold ya through the night

I know Tribemom’s not here right now and we don’t know why

We fear how we feel inside

It may seem a little crazy, pretty Rube,

But I promise Tribemom’s gon’ be alright

And if you ask me too Daddy’s gonna buy you a mockingbird

I’mma give you the world

I’mma buy a diamond ring for you

I’mma sing for you

I’ll do anything for you to see you smile

And if that mockingbird don’t sing and that ring don’t shine

I’mma break that birdies neck

I’ll go back to the jeweler who sold it to ya

And make him eat every carat don’t fuck with dad (ha ha)

I’m audi 5000, peace!