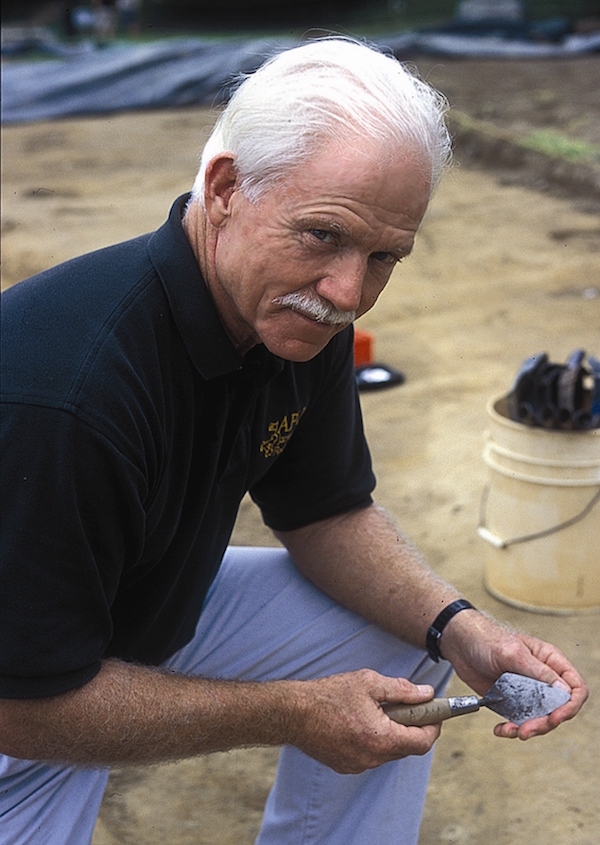

The leaves were just starting to change when William Kelso M.A. ’64 arrived at the College of William and Mary. It was 1963 and Kelso, now the Director of Archaeology at the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, had enrolled in the College’s master’s program in early American history.

“I’m walking down the brick walkway along the Sunken Garden and … the pure beauty of the campus hit me,” Kelso said. “It’s like I had walked back in time, in a sense. Back to the period that I was interested in.”

It wasn’t long before the program’s intense workload hit home.

“Once I got in class, I realized that I was going to have to work really hard,” Kelso said.

Early American history had become the focus of the Ohio native’s undergraduate studies at Baldwin Wallace College. Kelso took a particular interest in Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. His curiosity was sparked during a study break, when Kelso happened to look at some old magazines in the school library.

“I saw … an aerial photograph of the Jamestown excavations that were done in the 1950s,” Kelso said. “I had read that this was the earliest permanent English settlement. That really wasn’t played up in textbooks at all back then … I thought wow, that’s 13 years before Plymouth.”

Kelso’s professor suggested that he apply for a fellowship at the Institute of Early American History and Culture, now known as the Omohundro Institute.

“He steered me right,” Kelso said. “He said, ‘No, if you really want to go to the best place for your specific interest, you really need to go to William and Mary.’”

Kelso received the fellowship and moved to Virginia with his wife Ellen, a teacher he’d married as a junior in college. The couple rented a two-room apartment by Queens Lake.

Things got off to a bit of a rocky start when the College’s fellowship check failed to arrive.

“For about a week and a half, we were living off fish out of the lake,” Kelso said. “There was a little boat and I … went out and fished. That was about the poorest I’ve been.”

When he arrived in Virginia, Kelso made sure to visit the Jamestown site.

“I wanted to walk around and look at that particular place,” Kelso said. “And that’s when [the park rangers] told me that the fort itself had washed into the James River … And I was real disappointed.”

The disappointment faded fast. Right away, Kelso started piecing together that the 1607 fort might not have slipped away into the water. He asked a park ranger about objects sticking out of an exposed bank.

“He just looked at me like, ‘You know, you have a point there,’” Kelso said.

Kelso went on to write and publish his master’s thesis on a colonial shipbuilding site along the Chickahominy River; however, not all of his academic pursuits in the program went as well.

In one class of about 12 students, the professor encouraged the students to critique one another’s assignments. Kelso remembers his classmates harshly criticizing one of his essays, which he had padded with “high-sounding” words.

“I thought, ‘I’m in the wrong place here. I shouldn’t be in graduate school,’” Kelso said. “It was the lowest, lowest.”

Kelso simplified his writing and began reading his work aloud to his wife before submitting. He also hunkered down to work in what is now Tucker Hall, which was originally the College’s library. He also enjoyed stopping by Colonial Williamsburg’s library, which used to be located along Duke of Gloucester Street near the site of the restaurant Seasons today.

In his spare time, the former college football player would watch Tribe football games and socialize with friends. Kelso befriended one English professor and accepted an invitation to a party at the man’s Richmond Road house. When he arrived, he was surprised to discover that the entire interior of house was painted black.

“He had these kind of Dracula clothes on,” Kelso said. “I said, ‘Well, this is pretty strange.’ But it was a lot of fun.”

Although he received his doctorate at Emory University, Kelso credits the College’s faculty with cultivating his interest in early American history. He noted several “all star” professors he’d had, including William Abbott, who eventually became editor of the University of Virginia’s George Washington Papers; Ira Gruber, who authored books on the generals of the American Revolution and James Smith, who went on to run the Delaware Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library.

“What I really learned was what I learned at William and Mary above all,” Kelso said. “Not to put Emory down. That’s just the way it turned out.”

Before heading down to Druid Hills, Kelso spent three years teaching history at Williamsburg High School and volunteering on digs in the summer. He also coached the football team, but found that it was not his calling.

“The highs are high and the lows are low,” Kelso said.

The highs are high and the lows are low,” Kelso said.

One summer, Kelso worked with British archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume on an excavation near Newport News. Kelso went on to work with Hume at Martin’s Hundred, a 17th century James River plantation within the estate of the Carter’s Grove plantation. Later on, Hume oversaw Kelso’s thesis on the Wormslow Plantation in Georgia, as Kelso worked to receive his doctoral degree in archaeology from Emory in 1971.

From 1971-1979, Kelso worked at the Research Center for Archaeology, housed in the basement of the College’s Sir Christopher Wren Building until it was moved to Yorktown and later Richmond.

Kelso went on to become director of archaeology at Monticello, alumnus Thomas Jefferson’s home, where he pushed for the digs to focus on slave-related sites.

By the 1990s, Kelso’s thoughts had turned back to Jamestown. 2007, the quadricentennial of the settlement, was on the horizon. Kelso sought out the private owners of the Jamestown site and proposed a dig to locate the 1607 fort.

“The simple approach was look, you’re going to commemorate 1607, the first part of the early settlement,” Kelso said. “Wouldn’t it be great if we could find it first? It was that simple.”

When the dig began April 4, 1994, the conventional wisdom that the site was in the James River was still pervasive among historians and archaeologists.

“Almost every single archaeologist I knew was like, ‘Bill, you’re a nice guy, but I think you’re out of your mind. There’s no way. It’s washed away,’” Kelso said.

Almost every single archaeologist I knew was like, ‘Bill, you’re a nice guy, but I think you’re out of your mind. There’s no way. It’s washed away,’” Kelso said.

Even Kelso’s faith in the site began to waver by the time the dig started.

“By the time we started, I was kind of doubting myself,” Kelso said. “But right away, jackpot.”

The excavation began turning up early colonial artifacts almost immediately. Kelso and his team went on to locate the 1607 fort in 1996.

2007 saw a renewed interest in Jamestown, along with celebrations involving Queen Elizabeth II, U.S. President George W. Bush and former College Chancellor Sandra Day O’Connor. That same year, Kelso received an honorary degree from the College during commencement. In 2010, Kelso was made a C.B.E., or Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, by the Queen for his work uncovering Jamestown, one of the first colonies of the British Empire.

In the years since, the Jamestown archaeological site has produced finds included in Archaeology Magazine’s most important discoveries of 2010, 2013 and 2015. The dig has uncovered everything from burials of the settlement’s elite to survival cannibalism to mysterious relics.

Kelso said that Jamestown Rediscovery’s upcoming projects focus on one year in particular: 1619. That is the year the House of Burgesses, the colony’s first representative assembly, gathered, as well as the year the first group of enslaved Africans were brought to Virginia.

Kelso, who lives at Jamestown, still returns to campus once in a while for a Tribe football game. His advice for undergraduate and graduate students is simple.

“You can’t go around thinking you already know more than the professor. A lot of kids do that,” Kelso said. “Listen. Don’t try to reinvent the wheel.”