In a 2007 interview for US News and World Report, a college administrator — male, like most of them — defended admissions practices that appeared to set a higher bar for women. Our school is named the College of William and Mary, not the College of Mary and Mary, he said. But looking at the decision-makers on campus nearly a decade later, one would be justified in saying that a fairer name for the school we attend would be the College of William and William.

Using data collected from the 2014 census and salary information, an article in this issue demonstrates that at every level of the College’s bureaucracy, positions of power are disproportionately occupied by men. It is worth quoting:

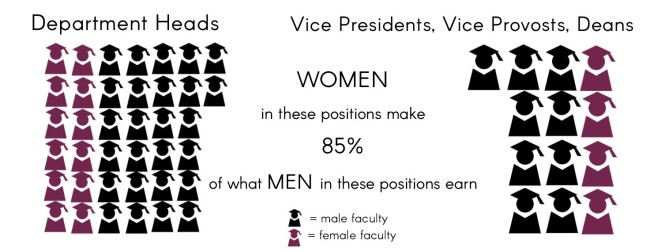

“Out of Vice Provosts, Vice Presidents, Deans and Department Heads, women at the College are paid 85 percent of what men in these positions earn.”

Nearly six in 10 students at the College are women … We can’t speak for all of them. But none of them deserve to work for 85 percent as much as their male counterparts.

“Out of 38 department heads, only 12 are female. Out of 13 vice provosts, vice presidents and deans, only four are female. The College has only had one female provost, and has never had a female president. Out of the 10 highest earners at the College, only one is a woman.”

These numbers are bleak. In the light of our student body, they’re an outrage.

Nearly six in 10 students at the College are women. Among them are future business leaders, physicists, journalists and politicians. We can’t speak for all of them. But none of them deserve to work for 85 percent as much as their male counterparts. Yet that’s exactly what the female leaders employed by the College do now.

Women at the College, whether working on research, teaching or serving in the administration, contribute equally to this institution.

Ellen Stofan graduated from the College in 1983, and today she is the chief scientist at NASA. If Stofan ever wanted to return to her alma mater to do research, the data published today suggest the College would not be able to welcome her to an environment that valued her contributions as much as her male colleagues’. This wasn’t acceptable in 1983 — and it isn’t now.

Shanta Hinton found out Feb. 5 that she would be the first minority professor offered tenure in the natural sciences at the College. But Hinton, who is black, prefers to focus on her research, not on the details of her race or gender. Hinton, and every woman employed by the College, should be able to focus on their job without having to worry that they are being paid less to do it because they are a woman. Today that’s not the case.

It is not easy to quickly change salaries or the employee population of an institution as large as the College. But it’s 2016. This should have been fixed years ago.

Women at the College, whether working on research, teaching or serving in the administration, contribute equally to this institution as men do. An individual’s salary, to some extent, is representative of how much an institution values them. By paying women less, the College is sending a sign — not only to the women it pays, but to all the women who are part of its community — that they are worth less than men.

It is not easy to quickly change salaries or the employee population of an institution as large as the College. But it’s 2016. This should have been fixed years ago. That it has not even been addressed suggests that the College’s decision-makers, from its President to its provost to its head of human resources — all men — might not have a stake in this issue.

Women make 85% of what men make because men have positions of greater responsibility (and in which they are available 24 hours per day, 365 days a year), as the article itself carefully points out to make a different — although no less ignorant — argument. And women do not hold as many of the higher positions because females generally make different life and career choices than men ( e.g. to have babies and start families).

The gender wage gap is a myth.

It comes because the Flat Hat Editorial Board does not know the difference between wages and earnings.