From “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” to “True Detective,” detective stories have proliferated our cultural consciousness for years. According to Professor Bruce Campbell, this detective craze in Germany has been clouded by one dark piece of the country’s past: Nazism.

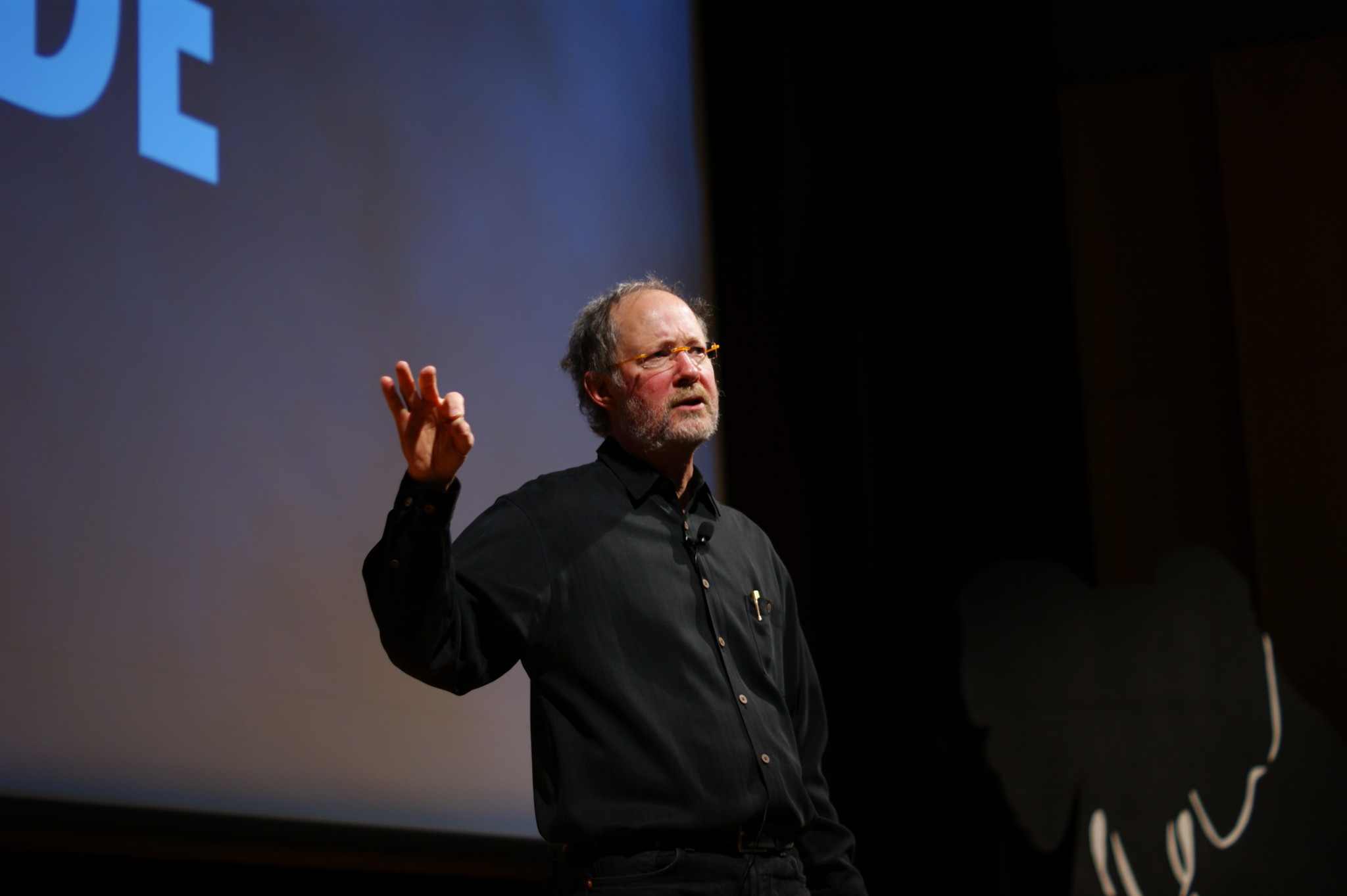

Professor Campbell was the speaker for this year’s Tack Faculty Lecture. This Thursday, his lecture, “The Detective is (Not) a Nazi: German Pulp Fiction,” described how literature, specifically German detective fiction, is a valuable tool with which to analyze the pervasiveness of Nazism in Germany’s culture. According to Campbell, fiction, even fiction as “popular” as detective fiction, can reveal deeper societal trends.

“For me, detective fiction is kind of a window into German culture,” Campbell said. “I’m particularly interested, when I look into that window, at how the memory of the German past operates in German society and specifically how it affects German detective fiction.”

His lecture was the tenth lecture in the Tack Faculty Lecture series. The series got its start in 2012, funded by Carl and Martha Tack, both graduates of the class of ‘78, with the goal of celebrating intellectual insight at the College of William and Mary.

Campbell joined the College’s faculty in 1999 after he received a Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in European history. He authored “The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism” and is currently the German studies program director and an associate professor of German studies. He has also taught a senior seminar on the German detective novel.

For his lecture, Campbell chose to focus on the intersection of fiction and memory in the context of postwar Germany. Having read American detective fiction as a child, Campbell perceived a difference when he began reading German detective novels. American detective fiction seemed to have a unique archetypal detective character, a character that Campbell called the “American-style hard-boiled detective.”

To illustrate the difference between this American “hard-boiled detective” and the typical German detective, Campbell juxtaposed the American detective from the movie “Dirty Harry” with a “grandfatherly” German detective from the television series “Derrick”. The former has his gun omnipresent and firing, the latter has his gun inactive and practically unnoticeable. This difference — the muting of such “hard-boiled,” gung-ho elements of an American detective — is a revealing choice, Campbell said. One of the main points of the lecture was that Germany’s remembrance of the former association between the Nazis and the police has complicated the typical characterizations of a world-famous genre for them.

“In a detective story, you ask the reader to identify with the detective, to live vicariously through the detective as she or he looks for the truth,” Campbell said. “The problem is, any German-speaking reader with any understanding of recent history … knows that there was a close link between the police and Nazi crimes.”

The German police were known to have played a major role in the executing of Nazi crimes. Nazi official Reinhard Heydrich, who was not only a major architect of the Holocaust, but was also the chief of the German police between 1936 and 1942, epitomizes this “close link” between Nazis and police for Campbell.

“In real life, the detective was a Nazi,” Campbell said.

Campbell went on to explain how, in fictional work, German authors try to sever this tie between Nazis and the police, constructing their characters in such a way as to avoid reminding readers of Nazi violence in the police force. The grandfatherly detective style in “Derrick” is one example of this trend. Campbell said that German authors cast their detective protagonists as American, female, homosexual, slow-moving and pot-smoking, all in attempts to signal to the reader that their detective is not a Nazi. Campbell had his initial revelation about this phenomenon while reading a novel by Richard Hey, a German author, who made his detective character female.

“It suddenly occurred to me that that wasn’t an accident,” Campbell said. “It suddenly occurred to me that … that was [Hey’s] way of getting around the problem of police duplicity with the Nazis.”

Campbell said such modifications come from trying to avoid the so-called “elephant in the room” that has haunted German culture since the end of World War II: the memory of a violent past.

“State violence is still a huge taboo in German-speaking society today, specifically in Germany,” Campbell said. “This is as important in literature and popular culture as it is in German foreign policy.”

Many members of the College community attended the lecture. Abby Whitlock ’19 said she enjoyed Campbell’s take on such a common genre in literature.

“It was a very thought-provoking lecture because it’s such a popular genre,” Whitlock said. “And the fact that a popular genre like that has its roots in something so dark and something that we try to repress is interesting.”

Owen Giordano ’20, one of Campbell’s students, said that the lecture helped him learn more about the differences in Germany’s take on the fictional detective.

“Like [Campbell] said, when I think of detective fiction, I think of all hard-boiled violence,” Giordano said. “But seeing how different cultures kind of react given the history and the recent past — it kind of makes me understand why there are so many different interpretations of a pretty, like [Campbell] said, a global genre.”

Campbell used part of the lecture to describe how important it is to keep analyzing characters and themes in literature and how in doing so we can reveal more about our society.

“Detective fiction can tell you an awful lot about culture … like all literature it reflects society’s morals, values,” Campbell said. “And of course detective fiction — it’s all about truth and justice … So I think it’s a particularly good tool to teach with and about.”