“Instant expulsion.”

It was during my first week at the College of William and Mary when someone asked about the steam tunnels. The response? An admonition that the administration strongly discourages students from going in the tunnels, so much so that if you’re caught underground, you are banished from campus, never to return.

It sounded a little melodramatic to me. To quote Hermione Granger, “We could be killed, or worse, expelled.” Perhaps the consequences of tunneling were exaggerated to instill a primal fear in the hearts of twamps. I had to learn more, and as I researched, the story kept getting better. This is a long one, so buckle up, put on your headlamps, and prepare for a wild thrill ride of history, superstition and plain old stupidity.

But first, a disclaimer, in case anyone from the administration reads this blog: don’t go in the steam tunnels. It’s specifically prohibited in the Student Handbook, along with other miscreant activities like climbing on balconies and roofs. Putting that aside, the tunnels are dirty and cramped, full of steam and asbestos, and infested with cockroaches. They’re not nearly as cool as you might think. Not that I would know, of course.

Let’s start with the basics. Why do we have tunnels, and what are they for? According to lore, most of the tunnels were built in the 1850s and were used to transport steam that heated the buildings on old campus. At the time, steam heat was pretty common, and you can find similar steam tunnels at other universities like Yale and Stanford. Just google “steam tunnels” and you’ll find dozens of accounts.

What’s unique about the College’s steam tunnels, however, is their patchwork history. In 1924, The Flat Hat reported the discovery of a mystery tunnel. During the construction of Monroe hall, workers found a long, brick passageway leading from the Sir Christopher Wren Building all the way to Lake Matoaka. Nobody knew what it was for, but it didn’t stop them from making some outlandish guesses. An escape route for military usage? An underground railroad for slaves during the Civil War? None of these seemed likely, as the passageway had no ventilation and was only three feet high by two feet wide. Its real purpose is probably much less dramatic: the tunnel was likely used to drain water away from the Wren Building. Still, this older tunnel adds to the mystery, as nobody really knows what it was for.

The reports of students in the steam tunnels are few and far between. According to interviews conducted by the WYDaily, a student lived in the tunnels in 1965, going above ground to shower and take summer classes. As amusing as this anecdote may be, I’m skeptical. The tunnels are heated to temperatures up to 375 degrees, and there’s little space to live or sleep without getting covered with grime. If the asbestos didn’t inflame your lungs, you’d probably get eaten by the mutant roaches before you could climb out to daylight.

This is just the first of these unsubstantiated, tunnel-related claims. Rumor has it that fraternity pledges used the tunnels to break into the Wren crypt, stealing bones and graffiting the walls. Verifiable? Not really. Likely? Oh yes. Multiple sources confirm that the tunnels do connect to the Wren crypt, and break-ins were enough of a problem that a padlocked steel door was installed in 1977 to keep people out. Plus, you really can’t underestimate the antics of fraternities.

In 1979, perhaps at the zenith of tunneling activity, The Flat Hat investigated the tunnels with the help of a student they referred to as “Subterranean Snake.” In an article which can only be described as “melodramatic,” the writer narrated their time underground. Damp, dark and full of hot pipes, the passages spanned between buildings and manholes. Sometimes having to crouch or crawl, the reporters meandered through the tunnels with the help of their guide, leaving markers on the manholes to find their way back.

In a blog post from 2006, an alumnus writes that he went on this Flat Hat expedition as an illustrator for the paper. They apparently went all the way into the Wren crypt, finding little but coffin liners and graffiti, the bones relocated somewhere else. The only illustration I could find was a comic about the tunnels, apparently drawn by “Ed Poe,” a ghost writer for The Flat Hat.

As tunneling grew in popularity, so too did the alarm of the administration. In 1979, five students were charged with entry into the steam tunnels. Reports are vague, but the Flat Hat reported that one of the students was charged with unauthorized entry and given an oral reprimand. Really? A stern talking-to is a far cry from instant expulsion. Still, the police chief at the time urged students to stay away from the tunnels, citing the potential for trespassing and breaking and entering charges. Besides, the tunnels were a safety hazard. Full of hot steam and sharp metal corners, the potential for student injury was too high.

By 1981, tunneling had become enough of an issue that alarms were placed in the tunnels to deter students from going underground, and doors to the tunnels and the Wren crypt were padlocked to prevent entry. With these extra barriers in place, the practice of tunneling slowly faded from fashion, with students finding other ways to defy the administration’s rules (climbing on balconies and roofs, perhaps).

Our story doesn’t stop here, however. Soon, a new generation of tunnelers would rise. With the help of the internet, they would write of their exploits, creating maps of tunnel entrances for future students, burying them on websites quickly lost to the fathoms of the internet. Or so they thought.

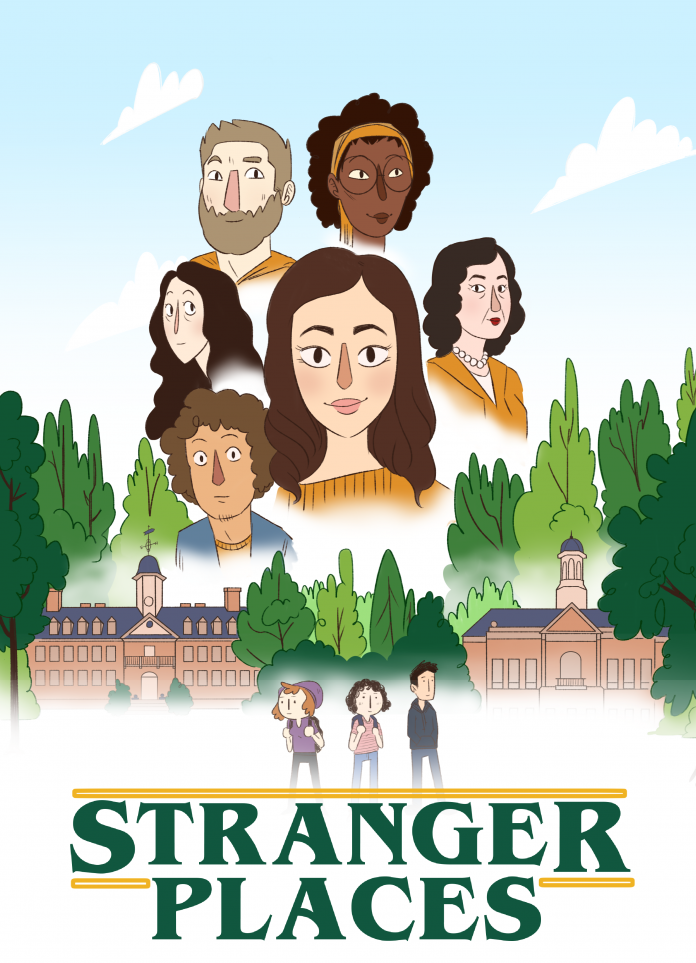

Next time, on Stranger Places, I’ll talk about the tunneling revival and explain how I found myself deep in an internet rabbit hole of archived websites and infiltration guides. Until then, I’d recommend staying above ground, or you may just receive a dreaded oral reprimand.