The Flat Hat investigated campus resources and trends surrounding sexual misconduct since 2015. In this article, The Flat Hat sat down with a College student who went through a university Title IX investigation last May and experienced administrative resources designed for her support.

Title IX filing and investigation

May 7, 2019, Kate Zabinski ‘21 reported a sexual assault to the College’s Title IX Office. The incident, which took place approximately three weeks prior, involved an alleged sexual assault by a student at the College, who will hereafter be referred to as the Respondent in order to protect the integrity of Zabinski’s report and maintain focus on her case’s outcomes and administrative process. Shortly after filing the report, Zabinski met with Haven Director Liz Cascone to discuss Zabinski’s assault case and the next steps Zabinski could take within the College’s multiple campus resources designed to support survivors.

According to Zabinski, Cascone showed her several flowcharts that illustrated several different outcomes that the university could pursue to resolve her case, including instituting interim measures like no-contact and no-communication orders. During the meeting, Zabinski explained that while Cascone mentioned she could go to the hospital or the police, Zabinski felt she was given limited guidance or assistance from Cascone to move forward with that approach.

Zabinski requested a Title IX investigation into her case as she was not satisfied with the restoration process or formal warnings to the Respondent that Cascone provided. Cascone then informed Zabinski that she would have to select a case adviser, an individual designated to walk complainants through the administrative process, and Zabinski chose Cascone. However, over the investigation process, Zabinski grew disappointed by the lack of communication she had with Cascone when the semester ended soon after their meeting.

“But then once I went home, I never had a phone call with Liz,” Zabinski said. “She never made it so that she was really approachable, and her check-ins with me as time progressed got less and less.”

After returning home in May 2019, Zabinski began working on her formal testimony, an experience she recalled as traumatizing, as writing her testimony required her to recount explicit details for the investigation. Written testimonials are submitted in Title IX investigations so both the complainant and the respondent have the opportunity to convey their experiences to adjudicators.

“I think she did her main core job of listening to me, giving me the resources and helping me start the process … But being my advisor and being the person that was designated to hold my hand … To look at an adult, at someone who works for the school and their job is to protect you … I didn’t feel like she put forth any of that energy.”

According to Zabinski, she attempted to solicit advice from Cascone regarding her testimonies but was let down by the level of feedback she received, often receiving short messages of approval rather than receiving edits to be incorporated into her statements.

When reached for comment, Cascone said that her role as an adviser restricts her to providing support and guidance throughout the administrative process and said that the role does not stipulate providing advice on written testimony.

Looking back at this stage of the Title IX investigation, Zabinski said she was disappointed by the support services that the College provided her, especially since she had not disclosed details of the incident or her investigation to many people in her personal life. “In my role as an advisor, I do not assist students in drafting written testimony,” Cascone said in an email. “Parties in an investigation participate in interviews with the Compliance and Equity Office. I attend those interviews with the party to provide support and help them understand the steps in the investigation process. After those interviews are completed, a report is drafted. When the report is provided to the parties, I will assist in reviewing the report with the party and discuss with the party any corrections, clarifications, or added information they identify that should be sent to the Determination Official to be considered.”

“I think she did her main core job of listening to me, giving me the resources and helping me start the process and explaining it to me,” Zabinski said. “But being my advisor and being the person that was designated to hold my hand, because I didn’t tell my parents. I didn’t tell anyone — I barely told any of my friends. To look at an adult, at someone who works for the school and their job is to protect you … I didn’t feel like she put forth any of that energy.”

Experiences with the Counseling Center and Care Support Services

July 1, almost two months after Zabinski filed her Title IX investigation in May, the College issued a ‘not responsible’ verdict, ruling in favor of the Respondent. Zabinski said she was surprised to hear that she had lost her case, given the evidence and witness support she submitted throughout the investigation.

“I remember just being shocked, and we sat there in silence for a good while because I went into shock,” Zabinski said. “I just stared at the table, and they just all watched me.”

While she was given five days to appeal the university’s decision, Zabinski’s summer job in Williamsburg working with the College’s history department made it difficult for her to devote time to the investigation, since the department’s planned festivities for July 4 required her attention during the appeal eligibility period. When she realized that she would not be able to appeal the case, Zabinski sought emotional support from the Counseling Center while still on campus in July.

According to Zabinski, she met with a graduate student for one appointment at the Counseling Center before leaving campus that summer, and she hoped that when she returned to the College that fall that she could resume working on her recovery there.

After returning to campus in fall, she was told that this graduate student no longer worked at the College and that she would have to meet with a new therapist with whom she would again have to disclose potentially triggering personal information. Eventually, Zabinski was referred to an off campus therapist in October 2019.

Expenses incurred by these off campus appointments were paid for by the College as part of Zabinski’s ‘wellness agreement’ with the university, which obliged Zabinski to regularly attend these sessions. Her wellness agreement also required her to meet with Care Support Services Director Rachel McDonald at the beginning of the spring semester in January in order to check in with Zabinski’s academic and personal well-being. At that meeting, Zabinski said she was again requested to disclose sensitive and triggering information while speaking with McDonald.

“So I just kind of talked to her, but she kept digging deeper and deeper and deeper into what happened to me and what I experienced and stuff like that,” Zabinski said.

“It was a snowball effect of people dropping the ball and neglecting me, forcing me to relive trauma.”

Ultimately, Zabinski said her experience with Care Support Services caused her to recognize how frustrating her journey through the College’s various administrative offices had become, since she perpetually found herself in a loop of retelling and re-sharing traumatizing information.

“Telling the care support woman of all the problems I had at the Counseling Center was traumatizing for me,” Zabinski said. “Telling the counseling center about all the issues that happened during the summer of the Title IX office neglecting me was traumatizing. And then, telling my new therapist of this, this and this William and Mary office neglecting me was traumatizing … It was a snowball effect of people dropping the ball and neglecting me, forcing me to relive trauma.”

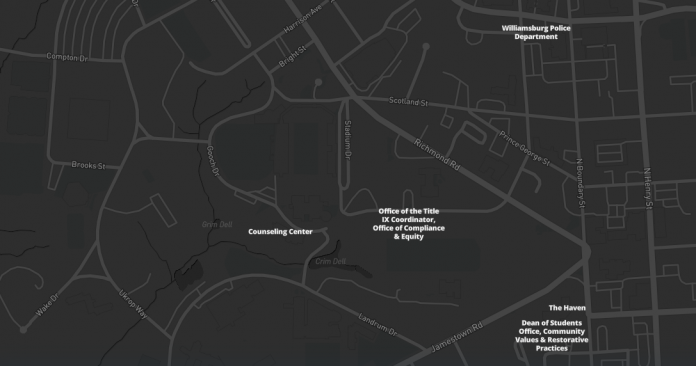

This map displays several administrative resources available for sexual violence survivors at the College and around Williamsburg.

When reached for comment, McDonald said that the Care Support Services Office is designed to support students and serve as an intermediary between students and alternative resources on and off campus.

“We advocate on behalf of students with faculty and staff for extensions, incompletes, and medical enrollment exceptions when appropriate, and refer them to both medical and psychological services as necessary,” McDonald said in an email. “CSS also helps some students manage their wellness plans (based on their health care provider recommendations) through education and referral support.”

Securing no-contact orders with the Dean of Students Office

Once Zabinski returned to campus in fall 2019, she requested a no-contact order between her and the Respondent. As described by the College’s website detailing interim measures for sexual misconduct cases, no-contact orders are designed to prevent retaliation and avoid the creation of a hostile campus environment. No-contact orders specifically prohibit intentional contact including electronic correspondence and non-verbal gestures between the order’s two parties.

Associate Dean of Students Dave Gilbert said that no-contact orders are created bilaterally and are designed to prevent intentional contact, but clarified that the university was not responsible for preventing parties from seeing each other in all contexts on campus.

“No contact orders are not intended to prevent parties from ever encountering one another on campus—on a campus the size of ours, such an objective would be difficult,” Gilbert said in an email.

“No contact orders are not intended to prevent parties from ever encountering one another on campus—on a campus the size of ours, such an objective would be difficult.”

However, Zabinski said that she felt the College had failed to do an adequate job in enforcing the no-contact order throughout the semester. On one occasion, Zabinski said that she encountered the Respondent while she was eating at Marketplace with her friend in early September. According to Zabinski, the Respondent approached her table and began speaking to her friend, causing Zabinski to cover her face and crouch closer to the table.

“I start having a panic attack, and my friends have to walk me down through Campus Center and to the Haven because I start freaking out about it,” Zabinski said.

Zabinski then said she met with Cascone in the Haven briefly before returning back to Marketplace, where she sent pictures to Assistant Dean of Students Dave Gilbert depicting where the interaction took place, with her friend posing in specific positions where Zabinski said the Respondent had stood.

Zabinski said that Gilbert then followed up with the Respondent regarding his potential violation of the no-contact order at Marketplace. Following this conversation, Zabinski was told that the violation had been deemed ‘accidental’ in a Sept. 4 email from Title IX Coordinator Pamela Mason.

Gilbert said that multiple factors are taken into account while determining if a party’s breach of the no-contact order is intentional.

“The institution evaluates the circumstances surrounding the reported contact to determine if it was unintentional or whether it became intentional contact through some action, like making prolonged eye contact with intent to intimidate, lurking in an area close to the other party after noticing their presence, or taking their time to relocate further away from the other party in a large area,” Gilbert said. “We also consider factors if the other party was engaged in conversation with other individuals that would make it more likely they were unaware of the party’s presence or if they were entering a public space on a regular basis because their student employment was located there and they have a non-harassing reason to be there.”

Zabinski said there were numerous instances where she encountered the Respondent in campus dining halls. Ultimately, these experiences caused her eating habits to suffer during the fall semester, since her concerns over seeing the Respondent during mealtimes were even more intensified than they were when she faced a similar situation while on campus that summer. Zabinski said that her avoidance of the dining halls placed significant strain on her personal health.

“I really thought I was gonna get sick or die, and not once did I receive disordered eating resources or a referral to the campus dietician,” Zabinski said in an email. “So multiple times I reported how [the Respondent’s] presence in dining halls affected me, making it clear that I was skipping meals multiple days a week to avoid him/having a panic attack. I dropped 20 lbs. extremely quick september-november because of how W&M handled my case.”

Zabinski said that she eventually received assistance in creating a dining hall schedule, but that she still struggled to feel safe on other campus spaces during the fall semester, especially at Earl Gregg Swem Library, where the Respondent worked. In January, Zabinski contacted Student Accessibility Services requesting the creation of a library schedule since she felt she deserved equitable access to campus’s academic resources, including visitation to Swem.

“I wouldn’t go to the library when the sun was down at all,” Zabinski said. “I would try to use the printers, but there were multiple times when I would start thinking and get upset and have panic attacks in the library … I didn’t feel safe at all.”

SAS referred Zabinski to contact Mason again. After Zabinski’s mother — who had since become aware of Zabinski’s case — contacted Mason demanding that the university create a stable library visitation schedule for her daughter, Zabinski met with Mason Jan. 30 to discuss her ongoing situations on campus.

“I wouldn’t go to the library when the sun was down at all … there were multiple times when I would start thinking and get upset and have panic attacks in the library. I didn’t feel safe at all.”

Mason sent a follow up email Feb. 5 suggesting that Zabinski provide broad time frames for her anticipated mealtimes, and while Mason said that she would encourage the Respondent to avoid those times at all possible, she ultimately reminded Zabinski that the no-contact order was difficult to enforce because of the College’s earlier case determination.

“As you recall, there was not a finding of responsibility and we do not have a basis for imposing sanctions,” Mason said in her Feb. 5 email to Zabinski. “We want to help navigate your schedule with as much peace of mind as possible.”

Zabinski said she was let down by the College’s inability to enforce a mechanism designed to support her as a survivor of sexual violence.

“I think the biggest takeaways are the lack of communication and then the lack of resources,” Zabinski said “… They paint a picture and then, they’re not doing anything to protect me and help me.”

Previous investigations into the College’s compliance efforts

The College has been investigated for its responses to sexual assault reports before. In March 2014, the United States Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights received a complaint filed on behalf of a female undergraduate student at the College. According to the OCR’s report, the complaint alleged that the College had done an insufficient job at promptly and equitably responding to the student’s report of an off campus sexual assault. While the OCR ultimately deemed that the College adhered to Title IX procedures, investigators were unable to determine whether the College completely fulfilled its legal responsibilities to consider the effects of the reported sexual assault, as well as to evaluate hostile campus environments that may have been encountered by the complainant following the alleged assault.

After reporting the assault, the complainant said that the university investigated the report and convened the Sexual Misconduct Hearing Board before ultimately finding the respondent, a male student at the College, not responsible for violating the university’s sexual misconduct policy.

The complainant claimed that the College’s handling of the case constituted discrimination on the basis of sex, a violation of Title IX. This claim initiated an investigation that included interviews with university personnel, investigators’ site visits to campus and analyses of formal documentation between the complainant and the College.

The OCR’s investigation concluded following an April 2018 memorandum to former College President Taylor Reveley III, which identified possible compliance concerns between the university and Title IX regulations in the complainant’s case. According to the report’s conclusion, it was unclear to OCR if the College made the student fully aware of all relevant remedial measures during and after the investigation. Investigators also stated that in this specific case, the university may have failed to uphold Title IX’s commitment to prompt action, since the student’s request for a ‘no contact’ order between her and the respondent was issued three months after her report. Finally, the OCR report found that the College could have considered providing supplementary resources for the student, including counseling and academic accommodations, that were not provided after her report.

“… I was so lost and scared, and was just trying to focus on school. Time to let it go and continue suffering, because nothing’s going to change.”

In closing, Zabinski felt she also experienced gaps in the College’s support for her throughout her Title IX investigation and her recovery process.

“It was always put on me, it was my responsibility to find people’s contacts and to find buildings’ addresses, and to go by myself,” Zabinski said. “These people had it in their responsibility to be like, ‘hey Kate, I set up a meeting for you’ … I couldn’t function, I couldn’t do things, I was so lost and scared, and was just trying to focus on school. Time to let it go and continue suffering, because nothing’s going to change.”

Editor’s Note: Digital Media Editor Claire Hogan contributed mapping graphics.