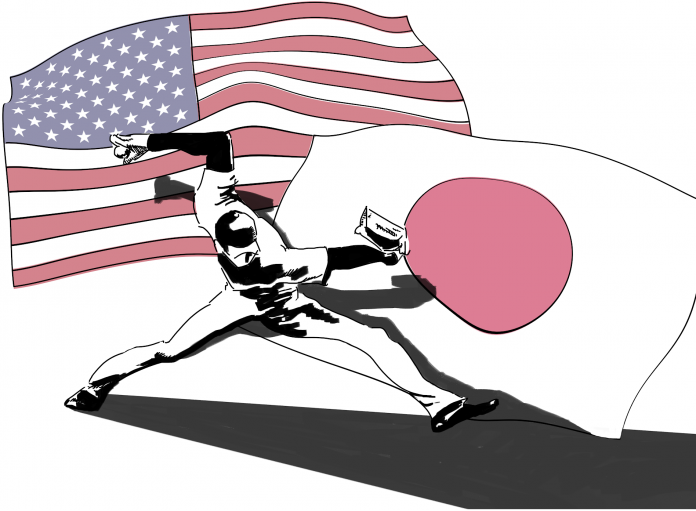

Marcus Holmes, chair of the College of William and Mary’s government department, has dedicated his career to studying and understanding the psychological aspects of diplomacy and international relations. In the midst of his career researching how human interaction affects countries’ and citizens’ perceptions of one another, Holmes is entering a new, exciting epoch. He is organizing an international Little League baseball game and an upcoming symposium at the College to examine Japan-United States relations through baseball.

Holmes’ interest in the psychology behind international relations began during his time in college, when the socioeconomic inequality he had witnessed as a child during a family vacation in India intertwined with his love for politically charged Russian literature. Together, the combination pushed him towards international studies, a master’s degree at Georgetown University and then a Ph.D. at Ohio State University. However, while in graduate school, Holmes’ skepticism for what he says are the rigid conventions of scholarly diplomacy led him to an avant-garde interdisciplinary approach to international studies after entering academia, drawing from the fields of government, international relations and psychology.

A key part of Holmes’ focus is examining the universal applications of international relations; he seeks to analyze how seemingly commonplace and mundane interactions between different nations have the ability to alter states’ perceptions of one another, he says.

“I naturally got led into diplomacy because that’s where the rubber meets the road, so to speak, with respect to actual humans doing international politics,” Holmes said.

Holmes described a key part of his theory regarding the importance of interpersonal interaction in diplomacy to be applying principles that guide conventional, state-level diplomacy to any level of international relations. This theory necessitates looking at the field of diplomacy as extending far beyond conventional interactions between heads of states and the diplomatic arms of their respective governments.

Holmes cited University of Pennsylvania sociologist Dr. Randall Collins, who is known for researching how emotional forces and interpersonal antagonisms shape society, as support for the idea that even miniscule international encounters can have a broader effect on societies at large. Holmes specifically pointed to Collins’ conception of how positive or negative interactions can radiate throughout societies, leaving a lasting impact in their wake. Taking this concept and broadening its scope, Holmes posits that the same holds true of any citizen-to-citizen interaction between countries.

“Whenever a tourist goes to India, a Little League team comes from Japan to the United States or a businessperson goes and does business in China, that’s interaction, too,” Holmes said. “I thought, ‘what parts of my theory on face-to-face diplomacy on the higher levels can apply on the lower levels?’ I think most of it can.”

Holmes explained that a significant roadblock in gaining recognition for his field of study is the difficulty that comes from data collection. He pointed to the case of the colloquially named “ping-pong” U.S.-China diplomacy (referring to the use of ping-pong matches to ease tensions between the two nations during the 1970’s) as being a notable case in which detractors could argue that positive geopolitical climates cause positive small-scale international interactions — the opposite of Holmes’ own theory. As he still lacks a way of applying his findings on the individual level to whole countries’ levels, Holmes notes that causation is still elusive. Though a common method of gaining insights into how international interactions occur is to simply survey travelers on their perceptions of other countries’ inhabitants before and after visiting these countries, he elaborated that it is not yet possible to reliably apply these types of personal interviews to prove large-scale causation.

Nevertheless, surveys measuring travelers’ perceptions before and after trips do indeed prove an increase in positive international relations at the individual level, he says.

“Ultimately, from an empirical perspective, a lot of this boils down to looking at the micro level as much as you can and trying to make the argument that, at the very least, I can show you that there’s change happening,” Holmes said.

Though he began his career with an academic interest in post-Soviet diplomacy, Holmes has expanded his purview to study the relationship between the U.S. and Japan, noting especially the positive effects that playing baseball — a highly popular sport in both countries — has had for their relationship. This shift was precipitated by a grant funded by the U.S. embassy in Japan celebrating 150 years of U.S.-Japan baseball diplomacy. In collaboration with Dr. Hiroshi Kitamura, a professor of history at the College with a special focus on Japanese culture, Holmes began building a project focused on the relations between the two states.

Kitamura elaborated on the importance of baseball in Japan. Although the sport originated in America, Japanese baseball fans have shifted baseball’s conventions to transform into a cultural activity that is accepted as mainstream and has been a uniting force for the two countries.

“Overall, I believe baseball, despite the different ways in which it may be played, is a force that has helped bring Japan and the US closer together,” Kitamura wrote. “If there’s no baseball, there’s a void between the two countries.”

The project will use the grant to invite a group of Little League baseball players to Japan in order to test changes in international relations at the interpersonal level. Holmes explained that the grant allows for a controlled environment in which to conduct the data collection that he has been lacking, making the opportunity a rare one.

“We said, ‘Let’s bring a group of Little Leaguers from Williamsburg to Japan, let’s practice what we preach and do it in a way that we can do it in a scholarly perspective,’” Holmes, who will also host a symposium at the College Oct. 27 prior to the trip to Japan in Aug. 2024, said.

Holmes emphasized a belief in the impressive power of sports in international relations, both on a larger-scale and in the effects that they could have at the interpersonal level. After the mutually traumatic breakdown of U.S.-Japan relations during World War II, he cited the importance of sports in allowing members of both countries to repair their perceptions of one another, respectively, and begin to recognize each other’s humanity.

“It could be something as simple as having a baseball team travel to Japan or South America to have interactions and play games together?” Holmes said. “Could it be possible that at some level, that is even at a very minute level contributing to this aggregation of goodwill?”