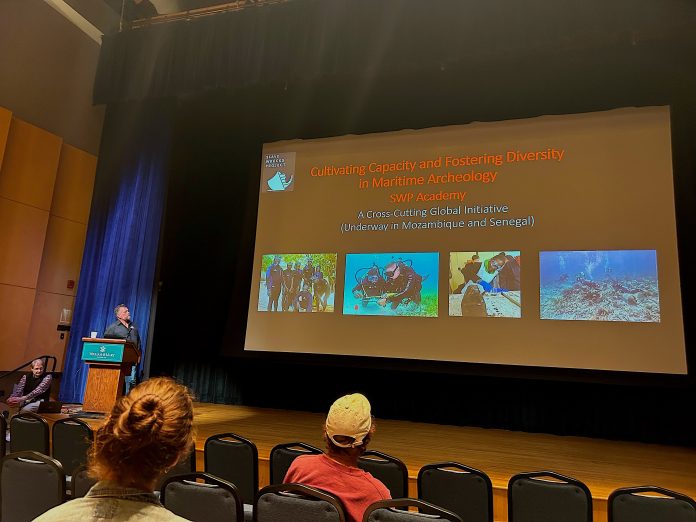

Thursday, Sept. 28, Stephen Lubkemann, director of graduate studies, anthropology M.A. program for second years and associate professor of anthropology and international affairs at The George Washington University, visited the College of William and Mary’s Commonwealth Auditorium to discuss his work as co-founder and international coordinator of the Slave Wrecks Project. The SWP is a network of organizations dedicated to interdisciplinary research and the history of the global slave trade using maritime archaeology. The College’s departments of anthropology, history and American studies co-sponsored Lubkemann’s talk, titled “Present Pasts: Slave Wrecks Project in Seven Shipwrecks.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture currently hosts the SWP, which partners with institutions such as the United States National Parks Service, GWU, Diving with a Purpose and Iziko Museums of South Africa.

“Perhaps the single greatest symbol of the transatlantic slave trade is the ships that carried captive Africans across the Atlantic never to return,” the museum’s website reads. “Locating, documenting and preserving this cultural heritage has the potential to reshape understandings of the past, making unique and unprecedented contributions to the study of the global slave trade.”

Chair of the College’s anthropology department and Forrest D. Murden Professor of anthropology Audrey Horning introduced Lubkemann.

“I have a longstanding interest in maritime archaeology, a longstanding frustration with public perceptions of maritime archaeology, in particular treasure hunting, and shipwrecks, as we all know, are sites of human trauma,” Horning said. “Many of these shipwrecks are, of course, associated with the horrors of the slave trade, so there is a legacy here to be engaged with.”

When we’re looking at the slave trade, we need to think about the way in which it shaped everything, in which it was a ubiquitous presence,” Lubkemann said. “It’s important to not just be a scholar of the slave trade, but to understand the ways in which the slave trade and enslavement shaped the world we live in today and continue to shape the world we live in today through the enduring legacies of this past.”

Lubkemann began by discussing the importance of the project’s work, mentioning that no other maritime process has impacted the modern world as much as the trans-Atlantic slave trade. According to Lubkemann, over 50,000 trans-Atlantic voyages were documented from 1500 to 1880, with 12 million enslaved people surviving the crossings.

“When we’re looking at the slave trade, we need to think about the way in which it shaped everything, in which it was a ubiquitous presence,” Lubkemann said. “It’s important to not just be a scholar of the slave trade, but to understand the ways in which the slave trade and enslavement shaped the world we live in today and continue to shape the world we live in today through the enduring legacies of this past.”

Lubkemann emphasized that when he and his colleagues began looking at this subject in maritime archaeology, there were only a handful of investigations into slave shipwrecks, many of which were motivated by treasure hunting. With the creation of the project, Lubkemann hopes he and his colleagues can help shape public pasts in a way that illuminates and reckons with history while engaging the public in transformative ways.

“The most professional archaeologists and the most professional historians here, when they step outside of their narrow area of focus, implicitly they’re relying on public pasts,” Lubkemann said. “Changing public pasts, I’m going to suggest, is important in changing professional past-making as well – in recalibrating questions.”

Lubkemann began his discussion of significant shipwrecks during the Transatlantic Slave Trade with the São José. This slave ship originated in Portugal and sank near Cape Town, South Africa in the late 1700s. Remains of the São José have been on display at the NMAAHC since 2015. The SWP is now working with colleagues in Mozambique to document the process by which the São José originated. Lubkemann mentioned how tracking the business operations of the owner of the São José has helped tell this history.

“We see the relationships between the different aspects of this person’s business, of this commerce in India that is intimately related and both inform and informing of slave trade activities that are occurring in East Africa,” Lubkemann said. “We have descendent communities that literally remember, have a living memory, of having come from Mozambique.”

Lubkemann mentioned that since Portugal was one of the most significant countries participating in the slave trade from the beginning to end, the SWP is also working with people in Lisbon, Portugal, to create the Heretics of Social Memory Working Group. The group is dedicated to fighting against the traditional ways in which public pasts are shaped. SWP is also working with the City Museum of Lisbon to raise funds for an exhibition and is beginning to help train teachers in the country to educate students about this part of their history.

“It’s interesting if you study shipwrecks, how many of those are actually attributable to the agency, the refusal of people to go quietly,” Lubkemann said. “It’s an incredibly important story to bring to the fore.”

Lubkemann then discussed the discovery of the L’Aurore shipwreck off the coast of Mozambique. After originating in Mauritius in 1789 and forcing over 600 people from Mozambique into slavery, these enslaved individuals aboard the ship staged a rebellion.

“It’s interesting if you study shipwrecks, how many of those are actually attributable to the agency, the refusal of people to go quietly,” Lubkemann said. “It’s an incredibly important story to bring to the fore.”

Later in the presentation, Lubkemann spoke about the future of the SWP and current initiatives the organization is working on. He mentioned that one of its goals is to foster more diversity in maritime archaeology and to give more agency for organizations involved in this work. Lubkemann stated the importance of creating sustainable institutions that will last beyond their initial creation. One of the elements that SWP has created in pursuit of sustainability efforts is called SWP Academy.

“Most of our colleagues from Mozambique, from Senegal, can’t either afford the time or they don’t have the resources to come here and do the training that we are privileged to have,” Lubkemann said. “We have blown up a masters curriculum to develop even further, and then transform it into a modular format that is delivered in three different languages in intensive periods in Senegal, Mozambique and eventually Brazil.”

Lubkemann mentioned that they are also developing a Community Stewards Initiative in Mozambique to focus on how local communities can monitor historical sites and resources to discourage treasure hunting. One of these initiatives includes teaching community members how to dive. Lubkemann also challenged audience members to reevaluate the methods used by their disciplines to study history.

“How do we change the balance, the calibration?” Lubkemann said. “This is the challenge we offer to archaeologists and maritime archaeology, in particular in the Slave Wrecks Project. What I hope the Slave Wrecks Project brings to archaeology and to researchers of the past in different disciplines is an understanding that if it is a social practice, it needs to engage in a much more multi-dimensional, in a deeper way, and justify itself in other terms.”

Lubkemann finished by mentioning that he hopes archaeologists and historians can use their disciplines to not only look at the past, but also deal with historical reckoning in the present. He then opened the talk up to a question and answer session.

“Reckon with and challenge representations of public pasts that continue to do work, often that is a continuation of the injustices and the disenfranchisement that comes from those pasts,” Lubkemann said.

Associate professor of history Andrew Fisher attended the talk and discussed the importance of the SWP in ethics and historiography.

“Dr. Lubkemann gave a fascinating talk that engaged not only with the historiography of the African slave trade but also important issues of scholarly ethics, community engagement and applied research,” Fisher wrote in an email to the Flat Hat. “He pushed us to think more carefully about why and how we do our work, including the responsibility of scholars to descendant communities and to participate in public discourse about the past.”

Horning also reflected on the talk’s importance in maintaining sustainable institutions and fostering public responsibility and participation.

“The work of the Slave Wrecks Project exemplifies the kind of engaged, ethical practice that we champion and that we want students to not only appreciate but to experience and ultimately to integrate into future career paths,” Horning wrote in an email to the Flat Hat. “We all are responsible for challenging the falsehoods of the ‘public pasts’ as Dr. Lubkeman discussed, and to strive for inclusion and sustainability in our practice as scholars and as engaged citizens.”