Griffin Amos ’24 is an English and Philosophy major that is pursuing his Master’s in Secondary Education with a concentration in English Education this upcoming summer. He is the Vice President of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. Contact him at gmamos@wm.edu.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

The holidays are coming up, and you know what that means: uncomfortable politically charged conversations with your distant relatives.

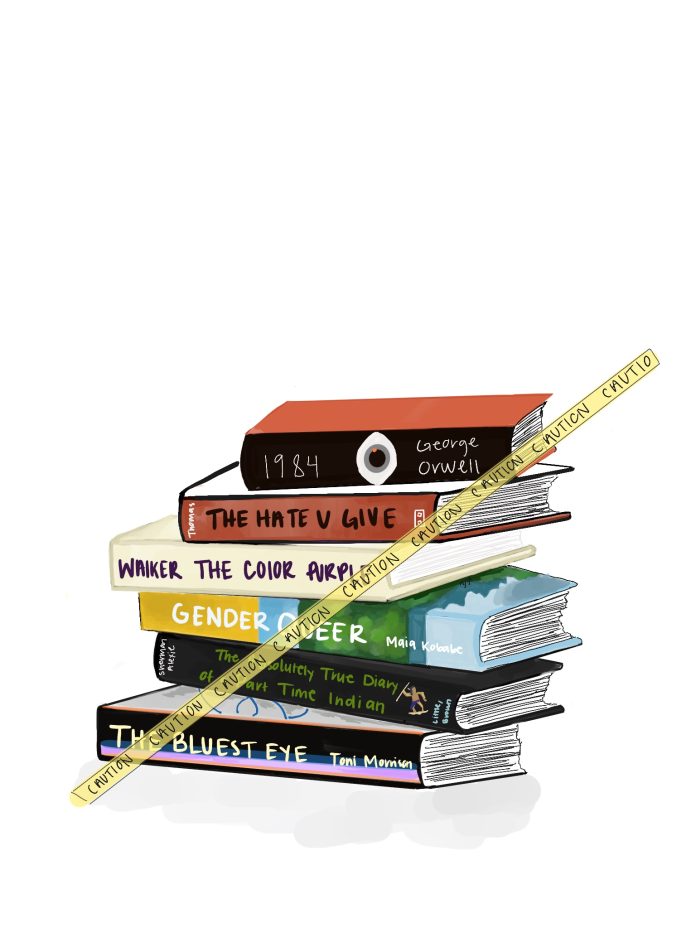

From the email we all received from Student Affairs about the topic to the widespread discussion and activism surrounding polarizing topics like the conflict between Israel and Palestine, it is clear that the question of how to effectively engage in civic discourse is currently a pressing topic. The recommendations in the email from Student Affairs after a brick was allegedly thrown through a window on campus are quite productive. In that email, Ginger Ambler writes that the “best way to combat speech is with speech,” and you should counter “bad facts with better ones, meet silence with sound, meet ignorance with education, meet positionality with dialogue.” These principles were perfectly put into practice earlier this semester at the College of William and Mary’s Banned Books Jam, in which individuals gathered at the Martha Wren Briggs Amphitheatre at Lake Matoaka to take turns reading and appreciating some of the beautiful prose from a laundry list of books banned around the nation.

I’m interested in bettering the conversation surrounding the drastic uptick in book bans across public schools in our nation, which is a repetitive, and frustrating, conversation because it is so heavily dominated by a vocal, vitriolic minority. Just in the first eight months of 2023, 356 different books have been challenged for bans across Virginia. Only 182 unique titles were challenged across all of last year, and that number was just a small fraction of that in years past. Across the entire country, challenging and banning books has been a rising trend, and last May Williamsburg-James City County schools chose to remove a book from the shelves of their high school libraries for the first time. The book in question is “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” by Jesse Andrews and it was removed because of a parent’s complaint over “f-bombs” and “phone sex.” With access to an unlimited supply of f-bombs and much more explicit content than verbal descriptions of phone sex via the internet, why are we targeting books such as this one that are also packed full of valuable lessons?

To summarize briefly, “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” is a story about a high school senior that is forced to come to terms with the death of his friend and must decide between his dream of going to film school or applying to a typical college. These are two problems that virtually every high schooler will experience in their time before graduating. Regardless of whether it is a friend or family member, students have likely experienced some death that impacted them by that point in their lives, and this book teaches young readers to grow from tough experiences like these just like the main character does.

The best way to get involved is to join the conversation, which can look extremely different based upon your interest in the topic, but the best first step is to start reading some of the most banned books. According to the American Library Association, the top five most frequently challenged books in 2022 were:

- “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe with 151 challenges across the country.

- “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson with 86 challenges.

- “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison with 73 challenges.

- “Flamer” by Mike Curato with 62 challenges.

- “Looking for Alaska” by John Green and “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” by Stephen Chbosky with 55 challenges.

Unfortunately, the uptick in book bans across the nation appears to be motivated by similar philosophies that underpin the widespread resistance to public school curriculum that frames lessons through the lens of race or many school districts’ bans on stickers that proclaim a classroom is a ‘safe space’ for LGBTQ+ students. In 2022, 45.5% of the books challenged for bans were written about or by individuals in the LGBTQ+ community. Additionally, 41% of the books that are currently banned across the country prominently feature BIPOC characters. Many pressing issues in education today are only issues because the dialogue surrounding them is so heavily dominated by groups like Moms for Liberty that want to ensure their children never encounter people that challenge their limited worldview.

Depending on your enjoyment of the books and care for the topic, getting involved can look as small as speaking up when that problematic uncle brings up how he feels about it, or as large as showing up to your local school board meeting to stand up for students’ right to read about controversial topics. If the College participates in Banned Books Week again next year, consider attending the Banned Books Jam, where you can appreciate some of the incredible writing that parents all around the country don’t want you hearing about.