“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”- 1972 Title IX of the Educational Amendments

By itself, the 1972 Title IX of Education Amendmenrs looks not only harmless, but absolutely necessary. Passed in 1972 on the coattails of a great decade of strides toward equality, the bill appeared to set a golden standard for a society against discrimination.

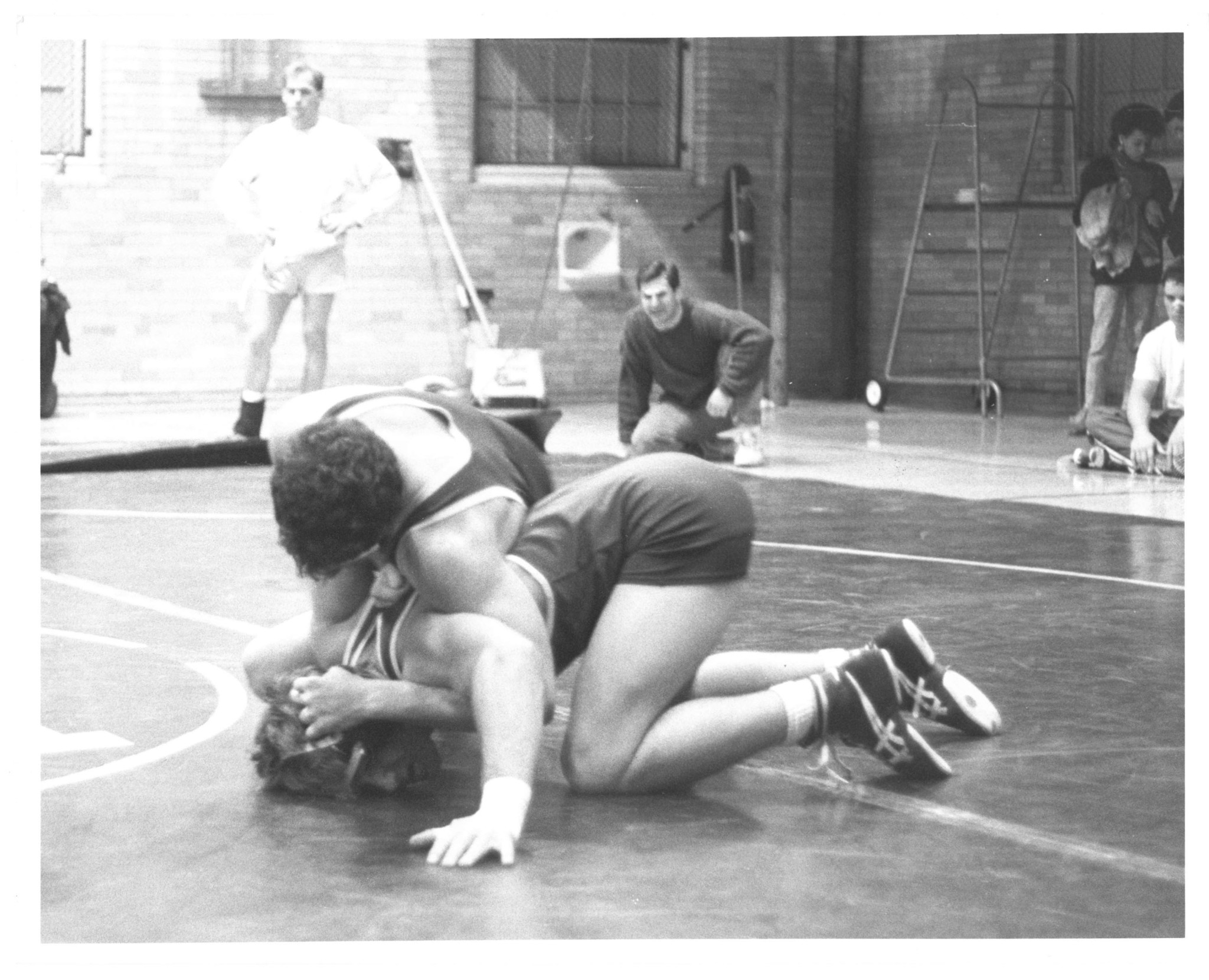

Coming off their fourth consecutive Southern Conference championship, the wrestlers of William and Mary had no idea that the bill would one day be blamed for the death of the Tribe wrestling program.

Such blame, however, is misplaced. Only slightly misplaced, and by seven years to be precise. A 1979 interpretation by the Office for Civil Rights within the Department of Education determined that a quota based on the proportion of student athletes was the best method to prevent gender discrimination at state colleges.

The ruling states that scholarships must be available on a “…substantially proportional basis to male and female athletes.” It goes on to say that “…effective accommodation means that if an institution sponsors a team for members of one sex in a contact sport, it must do so for members of the other sex” under circumstances such as “the other sex’s opportunities historically being limited.” Another stipulation adds that “intercollegiate level participation opportunities for male and female students are provided in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective enrollments.”

In plain English: If 44 percent of a school is male, then 44 percent of the school’s athletic opportunities and scholarships should be allocated toward men. No member of Congress ever voted on this interpretation.

Former Tribe wrestling coach Glenn Gormley ’80 shared his thoughts on the law and its interpretation.

“I’m not a lawyer, but there’s no way every major is divided equally between men and women, and I don’t know why that would tie into sports either,” Gormley said. “Proportionality doesn’t affect class, band or choir; why should it affect athletics?”

With no direct female counterpart to offset the scholarships so crucial to collegiate athletics, college wrestling has been on the ropes fighting over its right to exist since the 1979 requirement. In 1982, there were 362 National Collegiate Athletic Association wrestling programs throughout the nation. By 2001, only 229 programs were left standing. Ironically, the National Federation of State High School Associations reports wrestling has been growing steadily since 1993, and ranks as the fifth most popular sport among male high school athletes.

With an arm propped on the worn wood of Williamsburg’s Green Leafe, a local bar, Gormley recounted stories of his days coaching at the College from 1984 to 1989, and of the greats of William and Mary’s proud past. And to be sure, there were many.

Rob Larmore ’90 achieved All-American status and a NCAA semi-final berth in his time with the Tribe. Larmore transferred to the College from the University of Tennessee after the Volunteers announced the cutting of their wrestling program, drawn to Williamsburg on the strength of his relationship with Gormley and his staff.

Ten wrestlers stand in William and Mary’s Hall of Fame, as well as a coach of the once-proud program. From 1968-1971, the Tribe claimed four Southern Conference titles, defeating the likes of Virginia Military Institute, the University of Richmond, and The Citadel. Even wrestlers outside the hall distinguished themselves: Max Lorenzo ’78 finished eighth in the 1978 NCAA tournament at 150 pounds, while Tom Dursee ’78 garnered 128 career wins.

A January 1978 issue of The Flat Hat bears the headline, “William and Mary Thrashes Virginia, 37-3.” In 1979, the Indians prevailed over Virginia Tech 21-12. Nowadays, both the Cavaliers and Hokies field nationally-recognized programs. Virginia Tech is ranked No. 9 and the University of Virginia, the surprise 2015 Atlantic Coast Conference champions, at No. 18.

Meanwhile, the Tribe’s club wrestling team sets up a table at the student activities fair.

“The problem with Title IX is that it limits opportunities for men’s sports rather than providing more opportunities for women” Gavin Oplinger ’16, captain of the club wrestling team, said. “Wrestling is definitely not suffering from a popularity issue. The National Collegiate Wrestling Association [hosts] our national tournament with 162 teams. Most teams present are clubs that lost their program.”

At the College, the program survived the first Title IX wave of program cuts before the equal scholarship requirement whittled the team down to a single scholarship by 1990 and eventually removed the team from national contention. Still, the team won the Virginia State Collegiate Championships that year. Yet wrestling hardly received recognition from the athletic department. Of the 25 sports offered, the football program claimed 38 percent of the scholarship budget alone in 1994.

The final season arrived all too soon in 1994-95. The Strategic Plan from the College’s Board of Visitors described their intent to downsize the athletic program to 23 sports by dropping wrestling and fencing.

As soon as the BOV published the Strategic Plan, then-junior assistant editor of The Flat Hat and varsity wrestler John Encarnacion wrote an impassioned article titled “Wrestling put in a Chokehold.”

“It is absolutely unnecessary and unproductive for the school to cut the program to try to meet its strategic goals,” Encarnacion said in the article. “The major reasons given for the move are gender equality, lack of endowment, and of course, saving money … The savings of cutting both teams is estimated at 62,000, and will be distributed to other programs. Why would the money not simply remain with the wrestling and fencing team?”

To put $62,000 — the combined budgets of the two programs — in perspective, the football program’s scholarship money amounted to over $800,000 in 1994.

Encarnacion, in other articles of the same year, pointed out the sacrifices made by the wrestling team to reduce their already-miniscule budget.

“We traveled in tightly packed vans, left for all-day tournaments the day of [rather than get a hotel], our locker space became more constricted with three other sports relocating into it … and our equipment is over a decade old,” Encarnacion said in the article.

Budgetary rationale for axing the program doesn’t add up. With the exception of the top eight percent of football programs (such as Alabama and Texas) and some basketball programs, no sport at the NCAA Division I level nets a profit.

“We were the most profitable team on campus because we had the smallest budget,” Gormely said. “No team makes money.”

Even if the Tribe received donations to cover the entirety of a varsity wrestling program’s expense, the team would not be allowed exist.

“Most teams can’t even accept walk-ons,” Oplinger said.

A 1996 further interpretation of Title IX determined that all roster spots had to be equally allocated to men and women. Limiting a college football program, to say nothing of cutting one, is akin to sacrilege. Football is a sport that has no female equivalent and nearly 90 roster spots. This ruling is a death sentence to small men’s sports that now can’t field a NCAA team. Multiple wrestling programs and associations have filed suit.

Selina Fuller ’17 swims at the Division I level for the Tribe. She said that Title IX is valuable for emphasizing women’s sports.

“Not me personally, but I think it encourages girls to compete because they know they have the opportunity at a higher level,” Fuller said, when asked if Title IX helped her career. “If there’s a way to fund and promote girls’ sports without cutting so many guys’ sports, that would be ideal.”

It would not be characteristic of wrestling to go quietly. A 19-17 victory over the Hokies marked the last varsity home match in 1995, in which Encarnacion preserved a two-point lead by refusing to be pinned in the final match.

Currently, the club wrestling team, captained by Oplinger, continues to carry the Tribe wrestling tradition and remain competitive. The team hosted Eastern Carolina University and Bridgewater College Feb. 22 in the team’s first home meet in four years.

Three wrestlers advanced to regionals the year before, as Oplinger placed fifth and Austen Brower ’14 placed second. Each qualified for the National Collegiate Wrestling Association championship tournament last year, where Brower took seventh. Oplinger advanced to nationals once again this past season.

Tribe wrestling dominated in the late sixties and seventies before any restrictions came to pass, distinguishing itself as one of the College’s stronger athletic programs. Though well-intentioned, Title IX and its interpretations effectively killed off a sport as old as the Olympics at the collegiate level. As long as Title IX stands, the College’s wrestling team will remain on the club level, all too aware of the program’s storied history.