We are living in a historic moment. As the coronavirus pandemic sweeps through the United States, the College of William and Mary’s campus has effectively shut down. Once bustling residence halls and academic buildings are silent as students practice social distancing wherever their homes might be, completing their classes from afar. It’s easy to think that this is a unique event, but with a campus that dates back to 1693, the College has seen it all before. Today, I’d like to bring you back a hundred years to the Spanish flu of 1918, and a small unmarked cemetery south of campus that reminds us of our history.

Although the Spanish flu was first reported in January of 1918, it didn’t start to appear in Virginia until the fall. There aren’t a lot of documents relaying the College’s history at the time; the combination of World War I and a global pandemic obviously wasn’t great for record-keeping. The Flat Hat failed to publish a single issue in fall 1918, leading to large gaps in our knowledge of student life. We therefore rely on bits and pieces taken from diaries, local newspapers and reports of various historians to fill in the blanks.

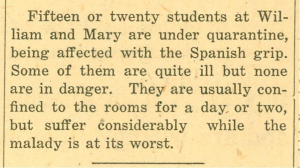

We do know this: within the first week of the fall semester at the College, students were sick with the Spanish flu. According to the Virginia Gazette, as of September 25, 1918, as many as 20 students were quarantined due to illness. It’s heartening to know that quarantine procedures were in place, but isolation for “a day or two” probably didn’t do much to stop the spread of the disease, which was highly infectious and deadly, with a mortality rate of around 2.5 percent. As a bonus historical fun fact, the Virginia Gazette referred to the disease as “the Spanish grip,” presumably derived from the Spanish word “gripe,” meaning “flu.” Although “grip” sounds pretty cool, I’m glad we’re not referring to viruses by their alleged nationalities anymore.

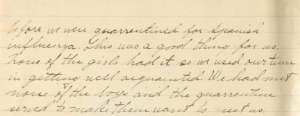

Martha Barksdale, one of the first women admitted to the College when it became coeducational in 1918, kept a diary during this time. One of her entries, dated November 26, 1918, describes the brief period in mid-September where classes ceased due to the quarantine. Rather than dwell on the negative aspects of the situation, Barksdale turned the quarantine into a social event, using it to get acquainted with the other girls living in her dorm. Talk about a silver lining!

“I arrived here on Sept. 19, and came up in an automobile with Ruth Conkey and Celeste Ross,” Barksdale wrote. “After several days we got straight and had classes one day before we were quarrantined [sic] for Spanish influenza. This was a good thing for us. None of the girls had it so we used our time in getting well acquainted. We had met none of the boys and the quarantine served to make them want to meet us.”

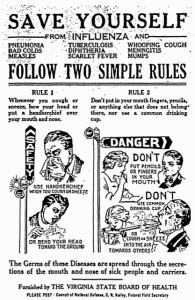

Despite Barksdale’s sunny outlook on the quarantine, the situation in Williamsburg and the surrounding area remained grim. According to “The impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on Virginia” by Stephanie Forrest Barker, the flu spread rapidly throughout Virginia, and in October, 1918, nearly 6,000 Virginians died due to the disease. Virginia state health officials began to take action, distributing thousands of flyers with information on disease prevention. Some counties took further action, closing schools, theaters and other meeting places. As you can see, history repeats itself.

With the pandemic continuing to ravage the population of Virginia, funeral homes were in chaos. Bucktrout Funeral Home, a historic institution dating back to 1759, kept records during this time, and they’re quite telling. In October 1918, Bucktrout Funeral Home buried more bodies in a single month than they usually would in an entire year. They were overrun and understaffed, and what’s more, they were running out of space. In the fall of 1918, Horatio Bucktrout decided to set aside part of his farmland to create a cemetery for those who died of the Spanish flu, many of whom were strangers to the Williamsburg area. As many as 36 bodies were buried there, and the cemetery continued to be used through the 1920s, before lapsing into obscurity.

According to “The Silence of the Graves” by Terry Meyers, originally printed in the Virginia Gazette in 1998, Bucktrout cemetery lies just a few blocks away from the College’s campus, south of Newport Avenue and east of Griffin Avenue. There is no remaining sign of the cemetery’s history: the area has become a suburb, paved over with asphalt and covered with houses, the bodies underneath long forgotten.

As we continue to push through the current pandemic, it’s often useful to reflect on our past. The 1918 Spanish flu was devastating, forcing the College to close, shutting down businesses, and causing thousands of unnecessary deaths, consequences that are all too familiar in 2020. But the College stood strong. In late 1918, the university reopened, and months later, much of society had returned to normalcy. Bucktrout cemetery, once a marker of the death and destruction caused by the pandemic of 1918, is now covered in greenery, a small park at the center of a thriving mass of houses south of campus.

Our situation now may seem unprecedented and unique but, remember the College has seen this before. Frightening as it was, the Spanish flu came and went, and the only concrete reminder of its existence, Bucktrout cemetery, remains in relative obscurity, lost to the annals of time. History marches on, and so must we.