After 60 years as a Williamsburg native, Shelia Ward still remembers the feeling of abject fear when at the age of five, her parents sat her down and explained what it meant to be a Black woman in America.

Recalling her childhood, Ward recounted a Williamsburg where members of the Ku Klux Klan would openly gather on Oak Tree Road near Pierce’s Pitt Bar-B-Que for local Klan meetings, or times where her brother and other neighbors would come home in tears after being chased with sticks and other items by white residents.

“I would hear my parents talk about KKK,” Ward said. “And it was like fear. It was fearful. It made me scared as a little girl because first of all, I didn’t know what that meant until they explained to me what it was. You know these are people who will kill Black people. They’re racist and they’ll kill black people. For me, it caused a lot of fear.”

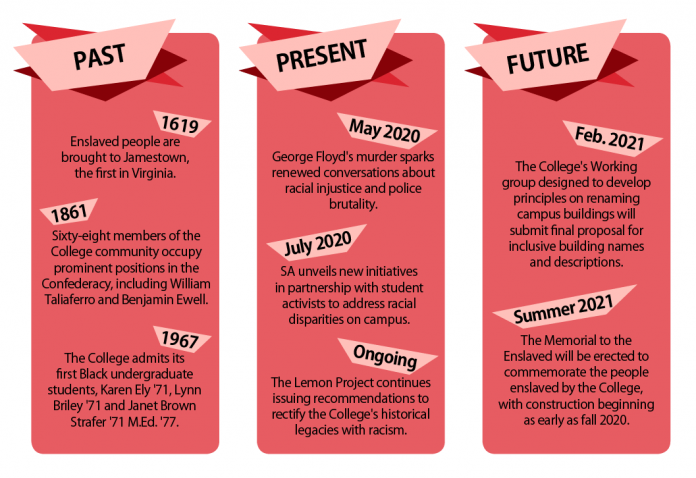

Only seven miles from Jamestown, where English colonizers set up their first permanent settlement in North America, Williamsburg played important roles in the creation of the United States. Being so near to Jamestown, where more than 20 African enslaved people were first sold in 1619 to settlers, Williamsburg has also bore witness to slavery and the perpetuation of racial discrimination in contemporary American society.

Although Ward notices substantial changes from her youth, she has also seen the ways in which racism has evolved, whether it be the subtle differences of not being greeted in a store where white shoppers are welcomed, or more blatant experiences like a couple asking her not to serve them at a restaurant because of her skin color. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, Ward explained that conversations around how racism is still occurring today have been brought to the forefront.

“It has gotten a lot better, but we haven’t arrived,” Ward said.

Past

Many of these conversations have opened up discussion in the Williamsburg community, as well as at the College of William and Mary. Established in 1693, the College has had a prominent role in the upholding and implementation of racist institutions in both the greater Williamsburg area and the rest of the country.

Executive Director of Historic Campus Susan Kern PhD ’05 works to study and uncover the College’s history stemming from the early days of the American colonies. Kern described how the College played an integral role in Virginia’s development, as well as in the laws that upheld and encouraged slavery.

“At this point in William and Mary’s history, we have a longer history with slavery than without slavery, which is also a chilling marker to think about how old William and Mary is and how we think about time.”

“William and Mary’s history with slavery is absolutely part of the record of how slavery as a legal structure evolved in Virginia,” Kern said. “We can use the long history of William and Mary and slavery and race during the Jim Crow era, and even after integration of campus, it reflects what’s going on in Virginia and nationally. At this point in William and Mary’s history, we have a longer history with slavery than without slavery, which is also a chilling marker to think about how old William and Mary is and how we think about time.”

While the College’s opening date in 1693 is ubiquitously well-known, it is less emphasized that the unrecognized labor of enslaved people allowed the College to prosper throughout more than half of its existence. According to Kern, not only do Jamestown and Williamsburg play a direct role in the earliest arrivals of enslaved peoples, but the College itself was prominent in propagating and shaping the North American slave trade.

As time progressed and the College navigated through American independence and the Civil War, Kern explained that the College played a leading role in upholding institutions of racism at each of these major historical markers, through forced labor to build iconic campus landmarks, its support of the Confederate army, and the College’s usage of labor by enslaved people on Nottoway Plantation to fund student scholarships.

Although many historians consider the end of the Civil War as the end of the College’s use of slavery, Kern noted that this was not without strong resistance from many of the College’s prominent figures. As noted on a Confederate plaque that was moved from the Wren Portico in 2015, a known 68 members of the College joined the Confederate army, including former College President Benjamin Ewell. Other known campus building share names with notable figures in the College’s unsavory past, such as William Taliaferro who held a position in the Confederate army or Lyon G. Tyler who continued to defend slavery as a positive good after the Civil war.

As the College progressed into the 20th century and the modern civil rights movement was born, the NAACP chapter of Williamsburg continuously worked to demand justice and change both at the College and within Williamsburg. According to The Lemon Project Director Jody Allen, this branch of the organization at different points housed speakers such as Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr.

“In terms of Williamsburg with the Civil Rights movement, a lot of that certainly centers around the Church, that First Baptist church,” Allen said. “It was a site of meeting … the churches within the community were usually the only property that blacks could own, they may have had their own businesses, but in terms of a collective meeting location usually it was the church. So, everything centered around the church … In the civil rights movement we know that the first Baptist was the sight of rallies … Dr. King spoke there, Rosa Parks visited, Jesse Jackson, it was kind of a hub within the Williamsburg community during the movement.”

The civil rights movement in Williamsburg experienced resistance from many locals, but Allen said it received substantial support from many College students. In 1951, Hulon Willis M.Ed. ’56 became the first black student to attend the College, earning an education master’s in 1956, and in 1967 the first three black resident undergraduate students, Karen Ely ‘71, Lynn Briley ‘71 and Janet Brown Strafer ‘71 M.Ed. ‘77 joined the College community.

Despite certain strides the College has made in addressing its historical legacies, students have recently begun renewed conversations pushing for greater racial equality and accountability from the College and different campus organizations.

Kern described the work that historians, students and the College are doing to understand this past with slavery and inequality and how important it is using these mistakes to push forward.

“We are working on what does reconciliation mean, what do we need to do to show people, not just saying we’re working on it, but to actually show people were learning from our research, and have made it part of what William and Mary is.”

“William and Mary is doing intensive work trying to understand what is the racial history that’s written into campus in ways that are so subtle you have to do research to find out and which ones are more obvious,” Kern said. “We are working on what does reconciliation mean, what do we need to do to show people, not just saying we’re working on it, but to actually show people were learning from our research, and have made it part of what William and Mary is.”

Present

As part of these efforts towards reconciliation, the College’s Student Assembly is reevaluating the mechanisms through which it guides and creates change on campus.

“I think that this is bigger than just saying Black Lives Matter. I think this should be about tangible change. … Racism evolves and it’s about time that we end that cycle and it’s about time that Black Americans have to no longer justify their very existence and it’s about time that we hold our institution, our peers and ourselves accountable.”

“I think that this is bigger than just saying Black Lives Matter,” SA Secretary of Diversity Initiatives Celeste Chalkley ’21 said. “I think this should be about tangible change. People are always shocked when they hear about racist incidences, and they say things like ‘oh it’s 2020 these things are still happening?’ When the fact of the matter, racism never went anywhere. Racism supposedly ended with the abolition of slavery or with the end of Jim Crow Laws. Racism evolves and it’s about time that we end that cycle and it’s about time that Black Americans have to no longer justify their very existence and it’s about time that we hold our institution, our peers and ourselves accountable.”

SA President Anthony Joseph ’21 described his administration’s efforts, including working with the Williamsburg police department to evaluate training and student arrest data, encouraging administration to hire more diverse faculty, and amplifying Black student voices as well as those of different marginalized communities by establishing new actionable committees.

Joseph said he would do everything in his power to ensure that his efforts to alleviate injustice in Williamsburg and at the College are actualized.

“One, I’m with you,” Joseph said. “I feel your pain deeply. I feel it when I least expect it throughout the day. It comes in waves and goes. It’s a familiar pain and it hurts. You feel it at the pit of your stomach and I feel that very well — I feel that a lot. So, I’m with you and I hear you. … That we are going to do our best this year to hold them accountable to that and put things in motion that will hold SA accountable to that. And not just SA, but this campus and William and Mary as well. We need to hold ourselves accountable to what we have done, what we are doing and also hold ourselves accountable to the opportunities presented to ourselves in the future to make change. That’s what I want to promise now to them that we make sure we keep that kind of pressure, that type of positive encouragement towards these tangible changes because it’s time.”

Outside of SA, student organizations are acting to eliminate racial inequality at the College. Multicultural groups, including the Black Student Organization and African Culture Society, have launched campaigns disseminating information about police brutality and anti-racist dialogue.

BSO member Victor Adejayan ’23 shared his experiences as a Black student at a predominantly white institution like the College, and explained the ways in which the BSO and similar groups are lobbying the College to prioritize diversity initiatives.

“I would like to see more diverse initiatives, you can’t have too much of that, targeting well deserving people from all different backgrounds,” Adejayan said. “Resources like the Center for Student Diversity should be expanded and better funded … I would like to see the CSD get a more central location, maybe like a Sadler Center, expanded facilities. They have a very important job and to many students it’s a safe space.”

Along with administrative changes, Adejayan and the BSO encouraged the College to implement equality, anti-racist and police reformation plans before tragedy strikes campus.

“I feel like as far as speaking on current events right now, what’s going on … I think that that’s a good start, what many students are looking forward to is real policy reform,” Adejayan said. “I haven’t heard of any cases where W&M campus police were having any type of bad interactions with Black students, that being said we shouldn’t have to have that happen before we see change. I want to see real things that will go ahead and protect us before anything even happens.”

Similarly, Adejayan described how limited visibility for Black students at the College leads to uncomfortable situations where individuals feel burdened to represent their racial background.

“I took a COLL 150 this last semester, there were maybe nine people, and I was the only Black person there,” Adejayan said. “It’s not the only class I’ve taken being the only Black person in there, or one of the few, and honestly for me and many others, we feel like we have this obligation to represent our race, which we don’t in any form; but it feels like oh, if I’m not saying something smart or I sound dumb, then I’m going to be propagating this stereotype, which is definitely something we shouldn’t feel … we shouldn’t feel the weight of our entire race on our backs at all times.”

As demands for accountability intensify, former Williamsburg city council member Benny Zhang ‘16 Ll. B. ‘20 described Williamsburg’s history dealing with racism and how the current anti-racist movements are pushing the city forward.

“We understand and stand in solidarity with the protesters, especially with Williamsburg and its past…” Zhang said. “It’s something that we are acutely aware of in terms of our positions even though we may be a small city government, we all believe we have a moral obligation moving forward to address the system inequities and fight for justice for all.”

During his time in office, Zhang helped create the state-wide Minority Business Commission, approved by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam and went into effect July 1. The commission will create policy to help promote minority business throughout the state, and has citizens commissions partnered with Williamsburg’s local NAACP chapter focusing on incorporating BIPOC more greatly into the Williamsburg community.

As students, organizations and community members push for change throughout the College’s campus and Williamsburg, Allen expressed the importance of keeping up this momentum and the perseverance necessary for building a more positive future.

“Hopefully this won’t go out of style,” Allen said. “That there will be a continued reaction and desire to make this a lasting change. That’s not going to happen overnight, it’s been 400 years since these cultures came together … you’re not going to fix 400 years of attitude, this is intergenerational; some of this hate has passed down from generation to generation it’s going to take more than a summer to fix it, but we can’t give up on it.”

Future

Joseph echoed Allen’s thoughts, emphasizing that meaningful work must establish structural change, which over the years will take the place of institutions of racism at the College and create a more welcoming campus for BIPOC students.

“This is going to take more than a year’s work because we are combating 328 years of a system that was propped up on the labor of Black people and now, doesn’t exist for them. I want to walk around like this school is my inheritance but frankly, I don’t feel like it is. And that’s what we need to change as well.”

“This is going to take more than a year’s work because we are combating 328 years of a system that was propped up on the labor of Black people and now, doesn’t exist for them,” Joseph said. “I want to walk around like this school is my inheritance but frankly, I don’t feel like it is. And that’s what we need to change as well.”

For Ward, who has experienced steps forward and backward throughout her 60 years in Williamsburg, she has noticed how fights for equality have given her granddaughter opportunities Ward did not have in her youth, and how recent events are culminating in national and local conversations.

“My spirit, I could feel that there was something there that I’ve never experienced before,” Ward said. “A crowd of diverse people coming together for a purpose. Seeing white people stand up for black people in Williamsburg.”

Correction: It was originally stated that Lyon G. Tyler held a position in the Confederate Army. This has been revised to specify that Tyler defended the institution of slavery after the end of the Civil War.