At last, it has been decided: Wednesday evening, a filled-to-capacity auditorium of College of William and Mary students cheering at exactly 116 decibels decisively proclaimed that the natural sciences are the most valuable academic discipline.

At least, this time, anyway.

The Raft Debate, an annual event hosted by the College, features an imaginary shipwreck that has left three professors stranded on a desert island. The survivors are always a humanist, a natural scientist and a social scientist. Each must argue that his or her discipline is more valuable than the others, and that he or she is the survivor worth rescuing. The winner is able to use the group’s only life raft to return to civilization.

Assistant professor of Hispanic studies John Riofrio represented the humanities, biology professor Dan Cristol represented the natural sciences, and associate professor of sociology Thomas Linneman represented the social sciences. A devil’s advocate, played by associate professor Sarah Day, argued that all three should have to stay on the island.

Dean of Graduate Studies and Research in Arts and Sciences Virginia Torczon played the role of the judge, mediating debate and stopping the participants if they went over their allotted time segments. Torczon began by explaining that, if they wanted to, the survivors could actually abandon the debate and try to come up with a solution to save all three.

“[They could] try to think of something practical, like figure out how to build a bigger raft,” Torczon said. “But that would be practical, and as it turns out, all four of them are professors.”

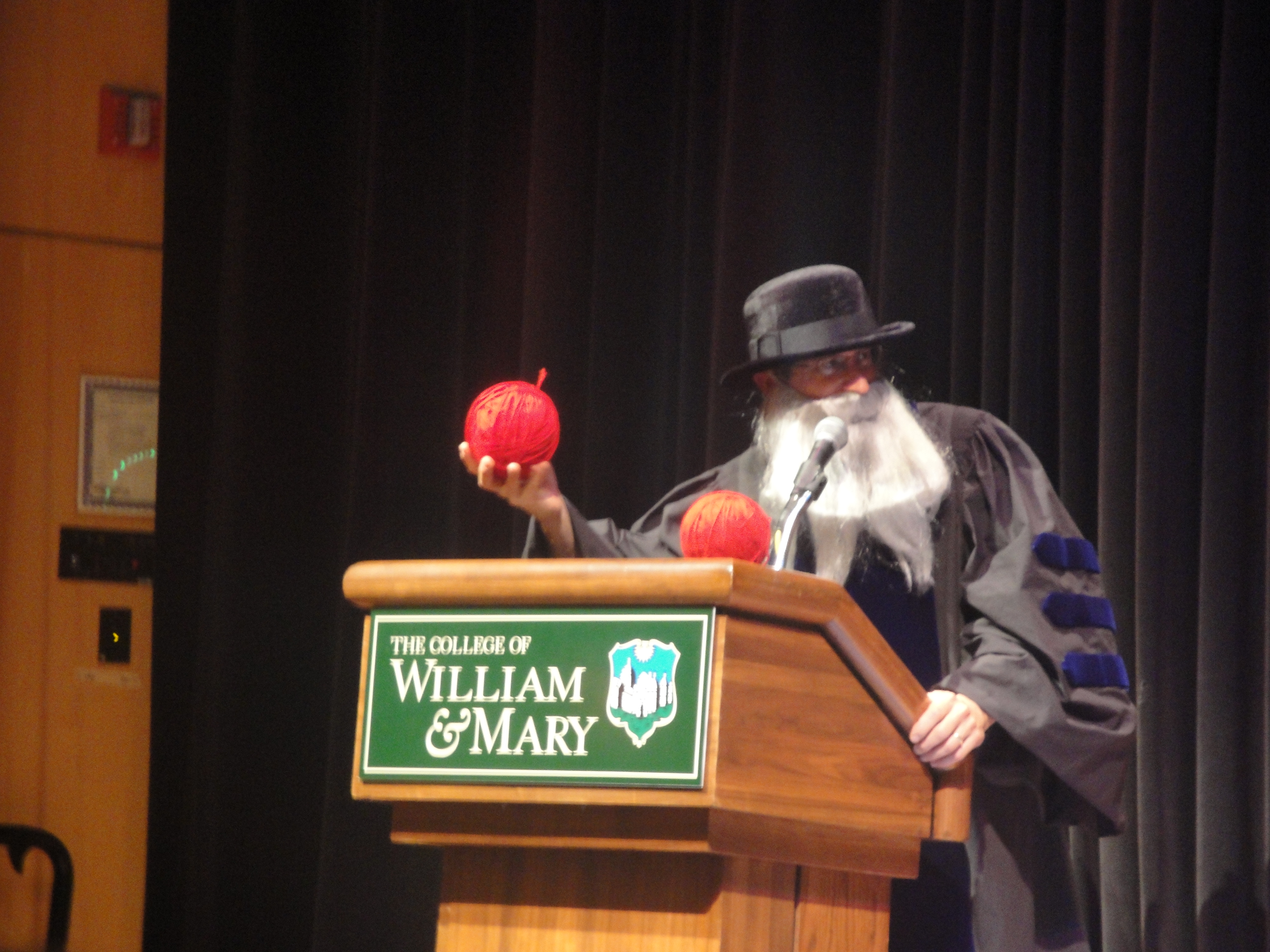

Torczon gave each survivor seven minutes to make his case, followed by three minutes of rebuttal. Cristol, dressed as Charles Darwin and donning a fake white beard that obscured the majority of his head and face, spoke first. He asked the audience members to close their eyes and imagine a world in which only the humanities existed.

“There are a lot of people scrambling around naked in the mud,” Cristol said. “When they’re not doing that, they’re critiquing each other’s poems, doing deconstructionist critiques of modernist transcendent architectural norms, and maybe watching a play in which the main character never shows up. Eventually, they all die from polio.”

And a world in which only the social sciences exist, according to Cristol, did not fare any better.

“[There is] a lot of discussion of how great diplomacy is, but then the government shuts down,” Cristol said to loud cheers. “And everyone dies from smallpox.”

According to Cristol, the other two professors might actually be quite happy to remain stranded: For academics in the humanities and social sciences, six years of total isolation from their students might be enough time to finish their next book.

When Riofrio came to the podium, he explained that the humanities are under attack — that education is turning into a standardized test score, and that critics are decrying humanities degrees as poor investments.

“Folks, this is not an investment. This is our lives,” Riofrio said. “This is the courage to study what we want to study.”

After arguing for the humanities as a path for only the strongest of will and heart, for those who want to spend their time and energy where their true passions lie, Riofrio tried to sway the audience using a new argument: Life on the desert island with Cristol and Linneman was simply too annoying.

“The worst is trying to live and cohabitate with Dan Cristol,” Riofrio said. “Every morning he’s up at 4:30 practicing bird calls.”

After a demonstration of Cristol’s birdcalls performed by Riofrio, Linneman took to the floor to defend the social sciences. He ran through an extensive list of all of the harms the natural sciences have caused, like violent video games, chemical weapons, and harmful drugs. And then there’s fracking, which Linneman said “just sounds evil.”

Linneman also argued that scholars in the humanities purposefully use obscure language in hopes that nobody else will ever be able to understand them — that way, they can always sound smart. He proceeded to quote one sentence written by philosopher Judith Butler, which took him 30 seconds to read and was 94 words long.

“Only seven of those words made sense and they were all the word ‘the,’” Linneman said.

Finally, the devil’s advocate began her speech, explaining why none of the professors should ever be allowed to return to civilization. She explained that all of the disciplines compliment each other — so if all three of the survivors can’t leave the island, they should at least stay together.

Near the end of the debate, the judge opened the floor for questions. One student asked matter-of-factly how each professor would combat giant monsters rising from the sea.

“I would take the monsters, and I would have them follow me down a narrow path, and I would lead them straight into professor Linneman’s and Cristol’s classes, and I would bore them to death,” Riofrio said.

Another student asked a question that didn’t seem clear to any of the professors.

“I kind of lost your question because I’m just a scientist and I can’t follow all the words,” Cristol said.

Based on a sound meter measuring the decibel level of applause for each professor, Cristol was pronounced a member of the most valuable discipline, and was therefore allowed to return to civilization on the raft. However, what seemed the defining moment in the debate belonged not to Cristol, but to Riofrio.

During his rebuttal speech, Riofrio called his two young children to the stage. He proceeded to play the guitar, accompanied by his son on the drums, while his daughter sang re-written versions of Rihanna’s “Stay” and Anna Kendrick’s “When I’m Gone.” (Lyrics included “round and around and around this debate we go” and “humanities, we think they should stay”).

“Since my dad made the lyrics, I didn’t really understand any of it,” Riofrio’s daughter, Isabela, said. “[During ‘When I’m gone,’] everyone was starting to clap and I felt really confident. I was trying to help my dad win.”

After the performance by the Riofrio family, as the cheers and applause died down, it was Linneman’s turn to deliver his rebuttal.

“I’m not even gonna get up,” he said. “When someone breaks out the children ….”

Linneman passed on the microphone. He knew he’d been beaten.