Yale University recently conducted a study indicating that fewer females go into science. The science community at the College of William and Mary has different opinions on what causes this disparity.

Professor David Armstrong, chair of the physics department, points to everything from innate biases to overt discrimination.

“A lot of it seems to be a problem in the pipeline,” Armstrong said.

The study also states “physicists, chemists and biologists are likely to view a young male scientist more favorably than a woman with the same qualifications. … Female scientists were as biased as their male counterparts.”

The New York Times reports that the gender gap appears to be a cultural issue that tells girls at a young age that math and the sciences are not for them.

Citing personal stories from female science students at various high schools, Eileen Pollack, the article’s author, describes various ways in which women are sometimes discouraged from pursuing science-related fields.

“In one physics class, the teacher announced that the boys would be graded on the ‘boy curve,’ while the one girl would be graded on the ‘girl curve’; when asked why, the teacher explained that he couldn’t reasonably expect a girl to compete in physics on equal terms with boys,” Pollack wrote.

Physics professor Irina Novikova believes there is a contrast in how women and men view failure in both the classroom and the workplace.

“Women tend to be way more critical of themselves than men,” Novikova said.

In Novikova’s opinion, when a female student or scientist finds herself not excelling, she will blame herself and her innate abilities. Many times comparisons are made to her male counterparts who do not associate failure with their personal abilities in their chosen field. She emphasized the importance of making a case for her students, especially if they are females.

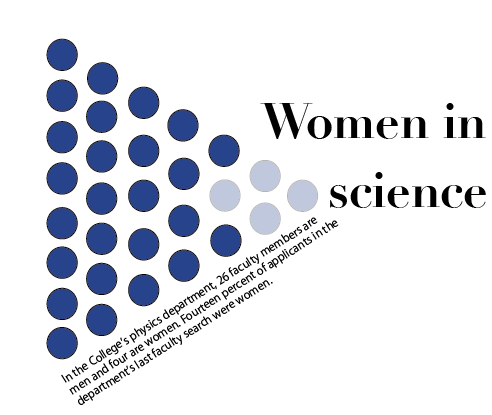

In the College’s physics department, 26 faculty members are men while four are women. Armstrong said that on the last faculty search, 14 percent of the applicants were female, matching the fraction of female faculty members within the department. He added that it could take years for a gender balance in a department to change since faculty positions don’t turn over on a regular rate.

Erin Goodstein ’17 intends to major in biology and public health. She has not encountered any gender discrimination in her studies, but she recognizes the gender gap to be prevalent in the sciences.

“I think that the current gender disparity exists because there is not a strong tradition of women in [the sciences], so girls grow up without role models to look up to in these fields,” Goodstein said.

Both Armstrong and Novikova placed heavy emphasis on middle school and high school cultures of thought and rigor. In order to combat this, Novikova works with an outreach program that sends science students to schools to show experiments and demonstrations to young students. She ensures that close to or more than half of the students who attend are female.

Armstrong also discussed existing biases that directly affect students in the classroom. Despite noting that overt sexism is effectively gone at the College, he believes it is important for people to understand this disparity.

“It’s important for faculty to understand that there are often subtle, unintentional biases against certain groups [in order to] avoid treating people differently,” Armstrong said.