Three-hundred-and-twenty-one years ago, the College of William and Mary held its first Blowout celebration on the Sunken Garden.

Okay, maybe not. But when did the ‘Blowout’ tradition really start? Or is it technically Last Day of Classes (also known in typical College abbreviation practices as ‘LDOC’)? And what about ‘Breakout?’

As students leave their residence halls this morning, they may sit in the Sunken Garden bouncy castle and ponder the origin of these ‘traditions’ and whether they truly are as old as our second-oldest college in the nation. Or, they might just stock up on free tacos to ruin their appetite for late-night flapjacks.

‘Breakout:’ The beginning?

In the 1960s, students referred to the final day of classes as ‘Senior Day,’ and the day marked a time when some seniors skipped class and rang the Sir Christopher Wren Bell.

“It was a lot calmer and a lot less of a general air of merriment and certainly not the bacchanalian display that it has become now,” Former Vice President of Student Affairs Sam Sadler ’64 said.

Sometime after the College went co-ed in 1918 and before the tradition ended in 1975 (old issues of The Flat Hat limit this to the late-1960s), students at the College participated in an end of classes event called ‘Breakout.’ The celebration began as an act of defiance against the limited visitation and curfew rules in place in the gendered halls.

“Students figured out that, if everybody denied those rules one night, probably nobody was going to get in trouble because the College couldn’t catch them all,” Sadler said.

The ‘Breakout’ festivities began after 11:00 p.m. when the residence halls were considered ‘closed.’

“Men on campus would come to the women’s dorms and ‘break them out’ and charge down to Colonial Williamsburg — [the] Williamsburg Inn — for a big party at the Williamsburg Inn pool,” Van Black ’75 said.

When visitation and curfew practices were relaxed and the College introduced self-determination, the tradition continued as a “symbolic campus-wide observance of the eve of the last day of regular classes for the year,” the May 9, 1975 issue of the paper reads.

“[There was] no advertising really about it anywhere,” Black said. “Everyone just really knew it was going to happen and, all of a sudden, there’s like a groundswell of people running through campus screaming at all the women in the dorms to get out. And then, more and more and more [people joined] as you went to Landrum and Chandler and Barrett and Jefferson and headed to the Williamsburg Inn.”

The Breakout tradition ended, however, in 1975 following the death of a freshman student who died in the pool during the festivities.

The origins of ‘Blowout’

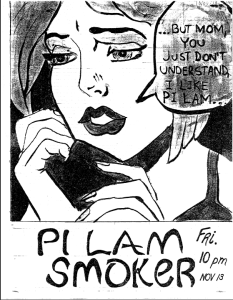

Following the end of the ‘Breakout’ tradition in 1975, the term ‘Blowout’ is first documented in flyers used by the Psi Chapter of the Pi Lambda Phi fraternity — or “Pi Lam.”

“Pi Lam used to have a party called ‘Blowout’ and it was their party. … So it was a Pi Lam function and I was always a little surprised, in some ways, to see that name move over to the other [campus-wide] event,” Sadler, a member of the College’s chapter of Pi Lambda Phi, said.

Before going inactive in 2002, posters promoting Pi Lambda Phi’s ‘Blowout’ in the University Archives date to as early as 1982 and Sadler said the event was held in the 1960s. The only poster that references the first ‘Blowout’ is the fall 1984 poster naming that semester’s event the “69th Annual End of Classes Blowout.”

But the timeline of growth for the term ‘Blowout’ into a campus-wide celebration remains questionable, and some, like Director of Housing Operations Chris Durden, attribute the 1970s- and 1980s-era term to the fraternity-specific Last Day of Classes celebration that later evolved into a campus-wide phenomenon.

John Farrell ’88 recalled the word “Blowout,” but could not place the exact meaning of it in relation to campus celebrations.

“I honestly remember that term from the 1980s, but I don’t remember what it originated from or how it came [about],” Farrell said. “But I think I just adopted it like the rest of campus did, but I honestly can’t remember how it originated.”

The evolution and spirit of ‘Blowout’

Although the term “Blowout” evolved in use in the 1980s and 1990s, the spirit of the Last Day of Classes’ festivities remained memorable to alumni.

For example, Farrell recounts a biology professor’s penchant for providing his classes with a cooler of beer at the end of every semester.

“At the time, you just thought that was cool,” Farrell said. “But, you know, after you leave the College … you realize that the faculty at William and Mary holds you at such high expectations and that’s not the same at other places. And I think they teach you to work so ridiculously hard and really kind of kick your rear end because they know what the world has in store for you — but then they’ll share a beer with you when it’s all over.”

“Blowout” has also shifted from primarily a senior-oriented event to a campus-wide one.

“I would say, for about 15 or 20 years from my time as a student forward, Last Day of Classes, when it did occur, was really an activity that seniors engaged in,” Sadler said. “It was seniors taking that day off and sort of defying going to class and, then, wise freshmen decided that, if seniors could do it, they could do it. And more people began to get involved and it just grew of its own momentum.”

Today, the Last Day of Classes includes a number of alcohol-free events around campus. Vice President for Student Affairs Ginger Ambler ’88 Ph.D. ’06 said the current activities began as an alcohol alternative for students as ‘toasting’ rose in popularity. ‘Toasting’ occurs when seniors return to their freshman halls to ‘toast’ the current residents. Derivations of this also occur.

“[Toasting] was something that, I think, started in the mid- to late-90s as something that students started to do,” Ambler said. “And so we really wanted to make sure the Last Day of Classes remained celebrative but also safe.”

Overall, the Last Day of Classes’s festivities offer a time of celebration for students as they finish another year — or in some cases, their last year — at the College.

“That calls for cheers and a drink,” Farrell said.

LDOC in modern memory

While based in tradition, there are some notable Last Day of Classes anomalies in recent memory. Including the 2006 bomb threat, which hampered the celebration but also provided an interesting source of amusement for students.

“[The bomb threat] was almost surreal. … But people had a lot of fun with the police, that was the strange thing. … People were getting pictures with the state troopers,” Durden said. “That was kind of an odd — but odd in a fun way — Last Day of Classes.”

The next year, a less threatening addition to campus altered the usual Last Day of Classes schedule — Queen Elizabeth II.

“All the traditional activities of bell ringing and all of that was moved to Thursday instead of Friday because the Wren Building was the site of the Queen’s visit, so there was a lot of preparation that was being done in advance of her visit,” Ambler said.

Although students might prefer to use the term ‘Blowout’ for the last day of classes event, Sadler may be to thank for the administration-preferred ‘LDOC.’

“I worked hard not to use that phrase, [‘Blowout’], because I think that it suggests an excessive drinking that was dangerous,” Sadler said. “So I tried to stay away from that, and I used to call it the Last Day of Classes, which students abbreviated at one point to ‘LDOC.’”

Steadfast traditions

While they may not date back to 1693 or even to Thomas Jefferson’s graduation nearly 70 years later, some traditions hold fast as staples of the Last Day of Classes experience on the road to graduation.

“[The Class of 1978] started a lot of end-of-the-year traditions, like your [Candlelight Ceremony] that you do the Friday night before graduation. … But some of those traditions that people think have been around since 1693 really haven’t been around as long as you think,” Black said.

One tradition that many, if not all, alumni remembered as indicative of their Last Day of Classes is ringing the Sir Christopher Wren bell.

“You know, it seems like such a little thing to those who haven’t gone through the College, but it’s such a big deal when you go. It’s just kind of a neat finality to it,” Farrell said.

Ambler described her anticipation in ringing the bell.

“[It] was very surreal because, before the age of the internet and being able to send photos via cell phones and things like that, it was very mysterious,” Ambler said. “The whole idea of what actually happens when you go to the Wren building and ‘Where is the bell?’ and ‘How does it work?’ … You sort of have this image in your mind of the Quasimodo moment where you’re jumping up and down and swinging on a giant rope and pulling the bell — it’s not quite that, but it’s still very meaningful.”

Although he didn’t ring the bell when he graduated in 1964, Sadler partook in the tradition when he retired 44 years later.

“Of the alumni that are living — and that’s a large number — I bet you that close to 90 percent have rung the bell at one time or another and most of them on their last day,” Sadler said.

Seniors: generation to generation

Despite evolving traditions, the final day of classes remains a poignant moment for one class in particular — the seniors.

“That very last day of classes, you’re certainly celebrating the accomplishment of finishing at such a difficult school like William and Mary and, at the same time, realizing that there are people that you will never see again, as much as you consider them contacts and friends,” Farrell said.

Farrell, Black and Ambler all spoke to fellow alumni or classmates to remember their final days at the College and to compare anecdotes from the Last Day of Classes. Black reached out to ten fellow graduates and ran into two other alumni before speaking about his last days at the College to The Flat Hat. Ambler spoke to a 2007 graduate and, in the same vein, Farrell spoke to four classmates within an hour after deciding to speak on the subject.

“It was fun to reminisce with them about the final days that they had because it was all that same thing, that feeling of the finality of it and, somewhere deep in your heart, knowing that things were never going to be the same. … It’s certainly a toast to those of the past and to the ones who are finishing [their time at the College],” Farrell said.

And on the ‘Last Day of Classes,’ or ‘Blowout’ or ‘Breakout’ or ‘LDOC,’ the students at the College participate in a collective event that, while ever-evolving, unites them generationally with 321 years’ worth of College alumni.

“A lot of our senior memories, I think, are very personal to us, as it should be, but the collective celebrations are always fun and that’s what ties us from generation to generation,” Ambler said.

As seniors ring the Sir Christopher Wren bell today and in two weeks when they proceed across campus and through the oldest academic building in the country, they follow in the footsteps of Jefferson and Monroe, of Stewart, Black, and Farrell, of Marshall and Ambler and Gates and Close — and, whether symbolically or literally, they become the newest generation of alumni connected to the College’s long history.

Flat Hat Managing Editor Abby Boyle contributed to this article.

![G0495A3[1]](https://flathatnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/G0495A31.jpg)

Getting out of Wm and Mary in the mid 60’s was marked by a sense of relief. The last day of all the semesters was characterized by a sense of fear and concern over how one was going to get through exams. There was none of this celebratory stuff, until the grades came back. It was an an awful experience. I remember working that last night at the Arms to get the bus fare out of town and I didn’t come back for 25 years.