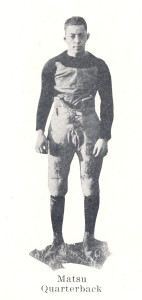

The College of William and Mary met its ancient rival Richmond on Thanksgiving Day 1926. Football Captain Arthur Matsu ’28 lined up under center in front of 7,000 spectators as the star of a school and state that would not fully accept him.

Matsu, the College’s first alumnus to enter the National Football League, was a four-year starter at quarterback. In 1928, 35 years after the founding of the program, The Flat Hat described Matsu as “the greatest quarterback that ever represented William and Mary and one of the best who ever played in the state.” Matsu’s athletic achievements were national news, as was his ethnicity. Born in Glasgow, Scotland to a Scottish mother and a Japanese father but raised in Cleveland, Matsu was the first Asian-American student admitted to the College.

Matsu’s race set him apart from the rest of the student body, as did his abilities both on and off the football field. Voted the “Student who has done the most for the College” as a senior in the 1928 Colonial Echo, Matsu was a member of the Seven Society and two honors fraternities, and presided over the Varsity Club his senior year. In addition to football, Matsu played baseball and basketball and ran track for the College.

Matsu was a star athlete, club leader and student scholar, but those titles disguise the extreme environment in which he lived and, astonishingly, thrived. While setting records and earning accolades both on and off the field, his state and school were actively denigrating mixed-race people.

In 1924, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act, which divided the state into two categories — white and non-white — and legally forbade interracial marriage. The law read: “It shall hereafter be unlawful for any white person in this state to marry any save a white person, or a person with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian. For the purpose of this act, the term ‘white person’ shall apply only to the person who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.” The law made it illegal for Matsu to marry any of his classmates and effectively criminalized his parents’ marriage.

Prejudice in Richmond was mirrored on campus in school publications and organizations. Though the vitriol was directed primarily at African-Americans, all non-whites felt the brunt of white supremacist sentiments.

An April 17, 1924 Flat Hat editorial ran near the end of Matsu’s freshman year, supporting the new law and railing against inclusive racial views.

“We cannot overlook the teaching of social equality, which can have but one ultimate result — intermarriage — unless the whites of the country are taught the meaning and priceless heritage they possess in a pure white race,” the editorial reads. The editorial lambasted states that had not taken similar measures against miscegenation, which would “result in the lowering of the higher race to the level of the lower.”

John Powell, a contributor and spokesman for the Racial Integrity Act, helped found a chapter of the Anglo Saxon Club of America at the College in May 1923. The club operated on campus for at least part of Matsu’s tenure. Twenty students attended the club’s first meeting. A 1924 Flat Hat article listed a section of the club’s constitution: “This organization stands … for the wise limitation of immigration and the complete exclusion of unassimilable immigration … for the preservation of racial integrity; for the supremacy of the white race in the United States of America.”

All of this occurred while the College’s star quarterback was a mixed race Asian-American man who was routinely praised for his intelligence and athleticism. Though Matsu’s ancestry was unacceptable in an environment of rampant racial hysteria, his feet, arms and mind were celebrated.

Football was a central part of life at the College in an era when games were dramatized as Homerian epics and cheering sections were vital to the reputation of the school. In a rule that defines the time, freshmen were required to attend all home games and stay the entire time. Students’ hypocritical acceptance of their team captain, at least as captured in records and publications, testifies to Matsu’s skill.

A child prodigy, Matsu’s athletic prowess was noted early on. At age 13, Matsu was the subject of a nationally syndicated column by Bismarck Tribune sportswriter Paul Purman, who detailed Matsu’s early athletic accomplishments. His maturation set off a recruiting battle between Princeton and the College, an established northern power versus an upstart southern program.

Matsu committed to the College and, in the course of his four-year tenure, helped build the Tribe — then called the Indians — into one of the strongest teams in the South. The College enjoyed a 24-12 record against an improved schedule over Matsu’s four years. The Indians had compiled a 16-19 record over the previous five seasons. flt_pg08_10-03-14

Listed at 5-foot-7 and 145 pounds, Matsu was the heart and soul of the College’s offense. Campus publications commonly called him a “triple threat man,” referring to Matsu’s speed, kicking strength and throwing ability. Matsu’s teams played larger, more renowned northern squads and often threatened an upset. The cover story headline of the Nov. 1, 1925 New York Times sports section read, “Harvard wins 14-7; W&M surprises: Matsu Amazes Crowd.”

The 1926 Colonial Echo detailed Matsu’s appeal: “Matsu has demonstrated his ability as one of the cleverest field generals ever at William and Mary. Aside from his precision and direction of the team on the field, ‘Art’ is a sensation in the passing medium.” While Matsu’s importance to the team was evident, his relatively reassuring biracial appearance may have contributed to the student body’s tolerance.

Professor Francis Tanglao-Aguas, director of Africana Studies, took inspiration from Matsu’s story in trying to build an Asian-American studies program at the College. He advances a theory for Matsu’s acceptance along this logic.

“In a way, his excellence in sports coupled with good looks prefaced the notion of the model minority syndrome that many Asian Americans (and possibly other people of color) face today,” Tanglao-Aguas said in an email. “To be precise, yet without taking any of his achievements from him, Art Matsu may have been able to successfully navigate the racist period of American history because he presented an image closer to the likeness of the pervading identity coupled with his extraordinary athletic abilities in sports clearly deemed as ‘American.’ ”

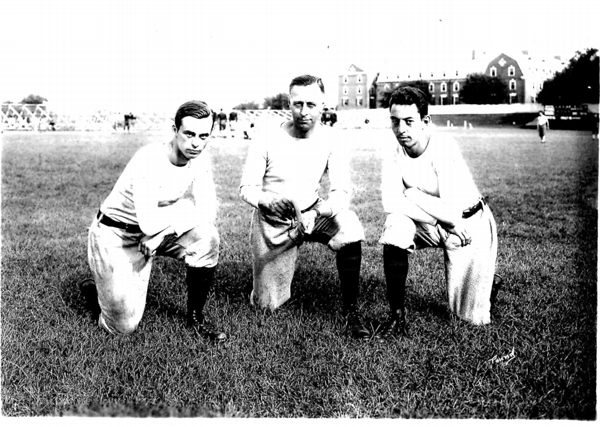

Later descriptions of Matsu portray a smart, tough and likable man. Matsu’s on-campus popularity was such that he even participated in a farcical ballet show with teammate Meb Davis ’28.

Fifty-four years later, Davis recounted the scene in the April 1980 edition of the Alumni Gazette. “Bow-legged Art in white stockings and fluffy dress falling in my arms!” Davis told the Alumni Gazette. “I carried him offstage over my shoulder!”

That “Art” became a hero for students, many of whom professed belief in the inferiority of his heritage, is undeniable and helps explain why 800 College students cheered on their team against its rival in Richmond on Nov. 25, 1926.

The College, under head coach Joshua Wilder Tasker, had become a state powerhouse by 1926. Matsu’s senior season was the finest campaign to date. The Indians came into the game against the Spiders with a 5-3 record, having dominated regional competition, falling only to national powers Harvard, Syracuse and Columbia. Matsu and go-to receiver Davis were selected to the all-state eleven by the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Matsu had not lost to the Spiders in his first three years, flattening them by a combined score of 61-12 and reversing the College’s prior series record of 7-24-2. Matsu and the Indians were the heavy favorites over the Spiders in 1926. Richmond kept the game scoreless until the fourth quarter, when Matsu and company’s offensive firepower broke through for two scores in the final minutes. The Indians amassed 471 total yards on the day in a 14-0 victory. The win sent the College to a bowl match-up with Chattanooga, which had tied for first in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association. The Indians triumphed 9-6 thanks to Matsu’s decisive 47-yard field goal.

In covering the Richmond game, The Flat Hat reported, “It was just a case of a weaker team, with its back to the wall withstanding the attack of a more powerful machine for three grueling quarters only to be subdued and beaten in the closing minutes of the contest.” The article went on to state, “Captain Art Matsu, playing his final game on Virginia soil, was in a great way responsible for the Indians’ showing.”

Matsu became a pioneer upon his entry into the College, and as he walked off the field victorious on Thanksgiving Day, he was a star in his own right. The College would not truly appreciate what Matsu did that day until decades later. A man of a “lower race” had beaten the Spiders and become a legend.

great article

[…] College Chaos […]