Hiba Vohra ’16 tries to pray five times a day, but she has trouble finding a quiet space where she won’t be interrupted. Sometimes she prays in the meditation room in the Campus Center. But sometimes she is on the other side of campus, studying in the library, and she feels guilty if she doesn’t walk the five minutes it takes to get back to her dorm.

She wants to learn more about her faith, but as the vice president of the Muslim Student Association at a college without a strong Muslim community, she is often considered the authority. There is no one to teach her.

For students like Vohra, maintaining a religious identity in college comes with a host of unique challenges — and for the first time, the College of William and Mary and the Student Assembly are trying to quantify what that means.

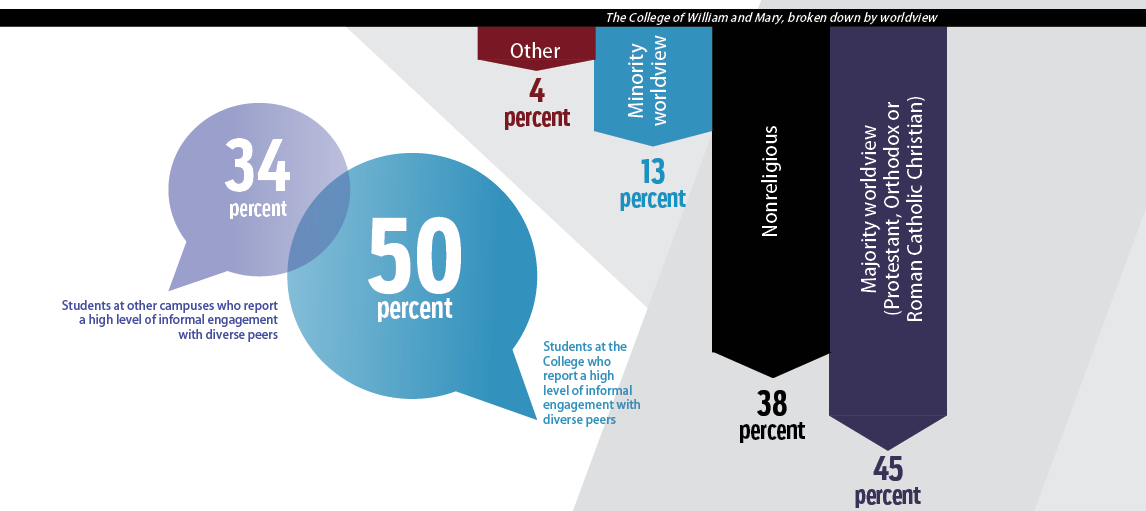

The Campus Religious and Spiritual Climate Survey compares students at the College with 13,776 students at 52 campuses across the country. The results, which were shared with The Flat Hat and will be released in full later this year, show a campus made up primarily of Christians (45.1 percent) and nonreligious students (37.7 percent). 12.8 percent of students identify as minority religions, and 4.4 percent identify as another worldview.

Based on the results, each participating college received a score in 26 categories. In 18 of those categories, the College’s scores are significantly different from the national sample.

Most of those differences are positive. Compared to other campuses, the College is more accepting of almost all religions and worldviews asked about on the survey: Muslims, Jews, Mormons, atheists and non-religious students are all accepted on campus at rates higher than the national average. For instance: 78.2 percent of students at the College report that non-religious students are accepted on campus, compared with an average of 60.3 percent at other campuses.

But for just one religious group — Evangelical Christians — the College is actually less accepting than most campuses. The survey asked students to indicate, on a scale of 1 to 5, whether they agreed that “Evangelical or Born-Again Christians are accepted on this campus.” The average answer was 3.53 out of 5.

Justin Schoonmaker ’09, an Evangelical Christian pastor for a campus ministry called uLife, said that there is no institutionalized discrimination against Evangelicals — but sometimes Evangelical students feel that their religion is at odds with academia. Their peers and professors don’t always have a nuanced understanding of their faith, he said.

“To be part of academic circles or academic groups that seem to take for granted — without questioning and without being willing to engage in dialogue — the opposite view of what Evangelical Christians hold on certain issues, I think feels threatening to them,” Schoonmaker said. “It feels unwelcoming to them.”

It can be easy, he said, for students and faculty to think of Evangelical students as having two contradictory mindsets: an “academic side,” and then an “irrational, spiritual side.”

“I don’t think that such a dichotomy exists,” he said. “We try to encourage our students to pursue both — to pursue their faith, but also to embrace scientific inquiry, because both are coming at truth from a slightly different angle.”

A spiritual crisis

But the notion that religion and rationality are at odds with each other is pervasive — and when Evangelical Christians come to college, sometimes they begin having doubts.

Every Wednesday night, Schoonmaker and his wife meet with students in their home. When students begin to question their faith, Schoonmaker encourages them to talk about their doubts during these meetings.

“Students are scared of the doubting and the questioning process, and I actually think Evangelical Christianity as a whole is not good at allowing adherents of the faith to question aspects of it,” he said. For instance: “A lot of churches would be afraid to talk about what are perceived contradictions in the Bible.”

Schoonmaker said that doubting is healthy and important — and he is planning to lead a meeting focused on perceived contradictions in the Bible in the spring.

Jodi Fisler, Assistant to the Vice President of Student Affairs and Director of Student Affairs Planning and Assessment, said she knows that students of all faiths tend to question their religious beliefs when they enter college. Fisler helped bring the survey to the College last year, and she hopes that the results will help inform the school’s programming.

“There’s a need on some students’ parts to have a place where they can go to explore spiritual questions, and we need to think about that, because spiritual identity and spiritual development is a key part of what it means to be human,” she said. “Helping students find avenues to explore that is something that is very important for us moving forward.”

Fisler added that providing opportunities for spiritual development is especially important during college, when learning to think in different ways can “put some people into a spiritual crisis.”

Jacob Robins ’16 is in the midst of such a crisis. Growing up, he went to synagogue with his family almost every week; now he goes to Temple Beth El, the Williamsburg synagogue, as often as he can. But when he enrolled in a religious studies class on modern Jewish and Christian thought, he was exposed to writings by theologians that “radically changed” how he views Judaism.

“It’s tough because I want to believe this new idea of God, but that would somewhat require a change in the liturgy,” Robins said. “I’m not willing to give up the traditional liturgy.”

Instead, Robins is trying to find a balance between the ideas he grew up with and the new ideas he’s learning in class. It is, he said, a process that will be “a life-long aspiration.”

Religious life on campus

Hannah Kohn ’15 is the SA’s secretary of diversity initiatives, but she first heard about the survey last year, when she was the SA’s undersecretary of religious affairs. Partnering with the Office of Student Affairs and the Center for Student Diversity, she led the initiative to bring the survey to campus. Now, she wants to get students talking.

“The definition of dialogue that I’ve learned after going to some trainings over the summer is listening deeply enough to be changed by what you learn,” Kohn said. “And that’s something that I really hope for on our campus. I hope that we can start listening deeply enough.”

According to the survey, students are already having a lot of conversations about religion and spirituality — at least compared with other campuses. 50.2 percent of students at the College reported a high level of “informal engagement with diverse peers,” compared with a national average of 33.9 percent.

Students at the College scored lower than the national average, however, when it came to participating in organized religious activities — joining groups like uLife or Hillel, for instance, or going to religious services on campus.

Vohra, the vice president of the MSA, wishes there were more organized religious activities for Muslims on campus. She is trying to get as involved with the College’s Muslim community as she can; the problem is that there isn’t much of one.

“It’s kind of hard to engage in religious services on campus — on this campus especially — because we don’t have a campus minister to lead prayer,” she said. “We don’t generally have structured prayers because we don’t have anyone to lead them.”

The MSA had a campus minister two years ago, but because of a miscommunication with the Center for Student Diversity, the group hasn’t had a leader since. They hope to find someone this semester.

While someone like Robins is able to participate in Williamsburg’s Jewish community instead of campus groups like Hillel, there is no strong Muslim community in Williamsburg. The closest mosque is five miles away, Vohra said. She thinks it’s in someone’s garage.

And because the Muslim community is so small, the MSA is often asked to act as the Muslim voice in Williamsburg. A few times, for instance, they gave a lesson in Islam to the United Methodist Church’s Sunday school. But Vohra feels uncomfortable acting as an expert on her faith.

“We don’t think we’re the best people to spread that knowledge because we’re just in college,” she said. “I still need someone who’s older than me to lead me. So if the school could help us find someone, like a campus minister, if the school could help us find a prayer or a study space — because there’s not a mosque here that can provide that for us — I think that would be really good.”

And for prospective students who want to be part of a strong Muslim community, Vohra added, the lack of resources could be a deterrent.

“Right now we’re just a club that meets in an academic building every week — but it’s all student-led, and we’re not as knowledgeable as we should be if we were to try to lead others in this faith,” she said. “I think we do need help from the school in order to establish ourselves better so that people can see us more as a legitimate resource.”