First, there was a box — wooden, graffitied and located smack in front of St. George Tucker Hall.

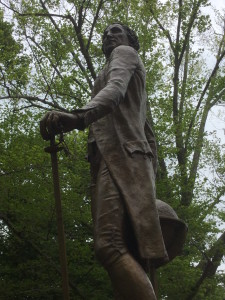

Passersby may have caught a glimpse of a granite base with a wrap-around relief through a gaping hole on the side facing the academic building. Then the box disappeared. On the base stood a tall bronze figure of College of William and Mary alumnus and United States President James Monroe, his gaze fixed on the Sir Christopher Wren Building.

Thursday, April 23, the figure was covered with a black sheet for the official unveiling ceremony. After ordering the crowd to fill in the empty chairs circled around the statue, College President Taylor Reveley kicked off the event with a reflection on Monroe, stating that he deserves more attention from his alma mater and the country.

“We are gathered to celebrate the arrival in our midst of a major new statue,” Reveley said. “A magnificent sculpted vision of one of William and Mary’s greatest alumni, James Monroe, who did not defect to the University of Virginia. So President Monroe will get a much larger statue here than Thomas Jefferson, and President Monroe’s statue will enjoy pride of place near the historic campus on a major thoroughfare. Mr. Jefferson is over there in a small courtyard.”

After remarks from Rector Todd Stottlmyer ’85, donors Carroll Owens ’62 and Patty Owens ’62 stepped forward to discuss the culmination of their decade-long venture.

The Donors

“We really have worked a long time on this project,” Carroll Owens said. “It’s run into a lot of roadblocks over the years. I’m just glad that somebody like Taylor [Reveley] could realize the significance of Monroe and what he means to the College today and in the future.”

In his speech, Carroll Owens commended Monroe’s legacy. He described the night of December 26, 1776, when a detachment of rebel forces crossed the ice-choked Delaware River and breeched the Hessian defense. Young Lieutenant James Monroe, who had just recently left the College to join the army, led the group. He was severely wounded in the fighting.

The sculpture of Monroe was funded entirely by the Owens’ 50th class reunion gift. While the idea has been in the works for about ten years, a formal commitment to the project was only made in 2010. The Owenses said that the project received strong support from College President Reveley.

The said they realized Monroe’s significance as undergraduates at the College. The Owenses first met sophomore year at a Kappa Alpha Valentine’s Day party. After graduating, Carroll Owens served two terms on the Foundation Board and the Athletic Foundation Board. Patty Owens served 13 years on the board of the Muscarelle Museum of Art.

They said that they were happy with the statue. Sculptor Gordon Kray ’73 produced the work.

“We are very pleased with the outcome,” the Owenses said in an emailed statement. “Early comments have been positive. We hope it will be a source of pride on campus and that students will welcome him as a fellow alum!”

The Artist

As an undergraduate at the College, Kray majored in art history and lived in Monroe Hall 107. Today, campus is dotted with his sculptures — from the tercentennial commemorative statue of Lord Botetourt in front of the Wren Building to the pair of sculptures of George Wythe and John Marshall outside the Law School to the Pierre L’Enfant statue in Miller Hall.

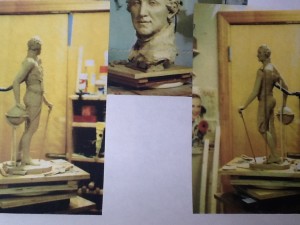

To prepare for the Monroe project, Kray read several biographies on the fifth United States President. He created both the bronze figure and the relief around the base, which features eight panels depicting various phases of Monroe’s life. He said that this aspect of the sculpture proved to be challenging at times.

“I’ve done quite a few sculptures, quite a few statues,” Kray said. He added that Monroe was particularly challenging because of the eight different subjects contained in the base. Another challenge, he said, was finding an appropriate pose.

“I wanted one what was stately but not too hackneyed,” he said. “As you know, we have a cylindrical drum here, and if one walks around the relief, you can sense a certain motion, moving around that drum, by the activity of the figures. I wanted the sculpture of Monroe to reflect that rotation. You can see that in the way he’s twisting around and turning from his hand on the globe to the hand on the sword. He is turning around and looking at the Wren Building. I originally had him looking at the Sunken Garden, but the Wren Building is where he studied, where he lived, it’s the College building and if he came to life, he would know it as such. So I thought it was quite appropriate to have him looking at the Wren Building.”

Kray said he was amazed by how small the statue looks from the Wren Courtyard.

“I think in the iconographic sense, it’s a nice process here. We have the Lord Botetourt out front, who was a great benefactor and loved the College and the students, but was a British nobleman. Proceeding through the Wren Building, you get one of our great American heroes on the other side.”

The sculpture is meant to represent the College’s colors — the bronze has a golden tint and the base is Green Mountain granite from Minnesota.

The globe on the statue is meant to symbolize the College’s international reach and Monroe’s status as a citizen of the world, as reflected by the Monroe doctrine and the subject’s term as an ambassador to France during the Reign of Terror. Kray noted that one of the stands of the globe did not fit on the base and remained unfinished. He also provided an alternate explanation for this facet of the sculpture.

“Monroe is supporting the world,” Kray said.

The sculpture and the base took about two years to complete. Kray studied historical paintings of Monroe to better capture his likeness.

“There were a lot of really bad portraits of Monroe,” Kray said. “He had a very complicated face. I know because I spent a lot of time on it … There were a few years of the sculpture that I was a bit sketchy about in my studio when I was looking at it. Now that I see all the views in context, there really isn’t a view I don’t like.”

Muscarelle Museum of Art Director Dr. Aaron De Groft ’88 said that he found the statue’s detailed iconography particularly pleasing.

“I think it turned out beautifully… I think Gordon did an excellent job transitioning these eight phases, these eight different stories,” De Groft said. “Nothing is arbitrary in those reliefs, in the sculpture. Every little thing means something.”

The Renaissance

The statue is intended to represent the beginning of a Monroe Renaissance at the College, an idea with origins in the College’s 1974 acquisition of the Ash Lawn-Highland property near Charlottesville, Va.

In 1793, Monroe purchased land adjacent to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. The estate would become known as Ash Lawn-Highland, which would be home to the Monroes for twenty-four years, until an indebted Monroe was forced to sell it in 1825.

Former Rector James B. Murray — who spoke on Monroe at the 2015 Charter Day ceremony — noted that it was Ash Lawn-Highland that first sparked his interest in the fifth United States president. While serving on the Board of Visitors, Murray became part of the Monroe Commission along with Caroll Owens and former Rector Jeff Trammell ’73. This group was tasked with assisting the president in making decisions to improve the operations of Ash Lawn-Highland.

“It became readily apparent that really what we should be focusing on is not the place but the man,” Murray said. “William and Mary can claim several United States presidents, but Monroe is the most famous of those who has no affiliation with any other institution. He only went to William and Mary.”

The Monroe Renaissance will incorporate a number of programs and celebrations building up to the 200th anniversary of his presidency in 2017. Murray noted that campaign would seek to expand research opportunities involving Monroe’s papers, work with the College’s history department to expand course offerings on Monroe and potentially even digitize Monroe’s body of written work.

“As we discussed Monroe and we read more about him, we began to realize that he really was one of the great American presidents,” Murray said. “He wasn’t a great writer like Jefferson. He wasn’t a great orator. But he was a fantastic leader of men and a remarkable international figure … The College has missed [an] opportunity. Virginia and the world have missed an opportunity to focus on Monroe the man and his contributions to building the country.”

The Reaction

Tiffany Broadbent Beker, a social media coordinator with the College’s Creative Services office, said that there is no plan to set up any sort of social media account for the Monroe statue. She said that she did reach out to the statue of Lord Botetourt’s account for a statement.

“We welcome Mr. Monroe to the College. By ‘we,’ I mean the corporate body of campus statuary,” Botetourt said in an email. “Well, to be candid, young Mr. Jefferson‘s nose was a bit out of joint at first, and we endured some muttering about the size and detail of the Monroe plinth and the new statue’s depiction of Monroe as president, as compared to the student Jefferson. But after Rev. Blair cuffed the whelp about the ears a bit, that discontent was ended, and young Jefferson now joins us all in making the fifth President welcome. Isn’t that right, Thomas?”

Other reactions to the statue were less positive. A faculty member who wished to remain anonymous noted that the statue is another prominent monument to a slave owner on campus.

“But here’s the rub: The statue has also prompted me to revisit the hazy histories of Monroe’s governance that linger beneath the bronze veneer,” the faculty member said in an email. “The statue has offered the starting point to productive conversations in and outside of the classroom, and to my students writing essays and making art. So, these are things I will think about when I pass (him) by.”

Lemon Project Director Professor Jody Allen said that she hopes that the statue will help spark a conversation about the College’s legacy on slavery. The Lemon Project is working on a fledgling project to establish a memorial to commemorate African Americans at the College, focusing on an era stretching from slavery to Jim Crow.

“What I’m hoping is that actually the statue will be of some assistance to us, in terms of being able to say that we have recognized our alumni who became presidents of the United States who were also slaveholders and now it’s time for us to remember the enslaved people who made their lives here at the College possible,” Allen said. “The people who fetched firewood and water and cleaned their rooms … we can’t tell part of the story, we have to tell the whole story. Hopefully, people will be as welcoming of a memorial to the enslaved as they are to these other monuments.”

Legum Professor of History Scott Nelson said that Monroe was a complex and sometimes controversial figure. He noted his energetic and stabilizing presence during the War of 1812, while also highlighting his decision to execute slaves during Gabriel’s Rebellion in Richmond in 1800.

“While he’s a student here, he breaks into the governor’s palace and takes weapons on behalf of the revolutionaries,” Nelson said. “He’s a controversial character, certainly… I’m less impressed with Jefferson and Washington than I am with Monroe. I just think he’s more interesting.”

Nelson said that he heard that the statue was especially controversial in the English department, as it is situated right outside Tucker Hall. Nonetheless, he said that he welcomed the sculpture, noting that Monroe’s presence has the potential to spark meaningful conversations about the nation’s origins.

“I’d sooner have a revolutionary on a pedestal than not,” Nelson said. “He’s someone that takes a lot of risks on behalf of the revolution against Britain. You could start to have a real conversation about what the country is about, whereas you get a lot of clichés when you talk about Washington and Jefferson. If you want to talk about what the country is and what its problems are, you can start by talking about Monroe.”

As a graduate alumnus of William and Mary (M.A. ’88), and as director of the James Monroe Museum in Fredericksburg, Virginia, I am very happy that the College is putting greater emphasis on Monroe’s legacy. Monroe was arguably the most experienced public servant to serve as President of the United States, having been a Revolutionary War hero, state and national legislator, governor, diplomat, and cabinet secretary. A full and frank conversation about his legacy is the right way to

approach the bicentennial of his presidency, which begins with

commemoration of the election of 1816 next year. William and Mary administers Ash Lawn-Highland, the Monroe estate in Albemarle County that is the only one of his homes open to the public. The James Monroe Museum, operated by the University of Mary Washington, has the world’s largest collection of artifacts and archives pertaining to him. These established sites will soon be joined by a historical “timeline trail” at the James Monroe Birthplace in Westmoreland County. When one also considers interpretation of Monroe at Colonial Williamsburg, at the Virginia State Capitol, and at Fort Monroe in Hampton, it is apparent that a “renaissance” in understanding James Monroe’s impact is indeed taking place.

[…] William & Mary begins its quest to start a James Monroe renaissance: https://flathatnews.com/2015/05/02/making-monroe/ […]