Language is important. Especially in places like William and Mary, institutions of higher learning that find life in dialogue and debate. In his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell said that one “ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting on the verbal end.” In the context of his essay, language was increasingly subjected to political bedazzlement, allowing the unsavory to pass as palatable, like those Walmart jeans becoming something everyone is suddenly wearing because rhinestones. I try not to speak for others, but I doubt there would be any disagreement that chaos has been one of the defining aspects of this election, and like Orwell observed, at least part of this has to do with the way we communicate.

I see language decaying in a very different fashion today, however, simply because it is being used less and less – replaced by pictorial icons, “trending” categories, sparse headlines and numbers. The utter lack of nuance in today’s politics is in part due to the lack of nuance in the ways we communicate our thoughts and opinions. How many times have a candidate’s words been taken out of context, manipulated, or otherwise misrepresented through the spreading of a clip that can fit into the headline of an article? And all one has to do to reinforce a piece of information is to click a button, bypassing any thought process, tapping into the reactive, emotional, and primal parts of our mind.

This puts social media at the forefront of this constriction of the English language, partly because it has evolved from its humble beginnings as just a way one connects with friends.

This puts social media at the forefront of this constriction of the English language, partly because it has evolved from its humble beginnings as just a way one connects with friends. Thus it follows that those particularly affected by this constriction are the groups that use social media the most, i.e., younger people, especially in college. We share more stuff than almost anyone (save the overzealous grandparent), and what we share has real-world implications. What becomes popular on Facebook becomes the subject of internet speculation (or vice versa), then television news coverage, then questions for potential presidential candidates, so it continues. And remember, popularity is not based on what gets the most “reads,” but what gets the most Likes and shares.

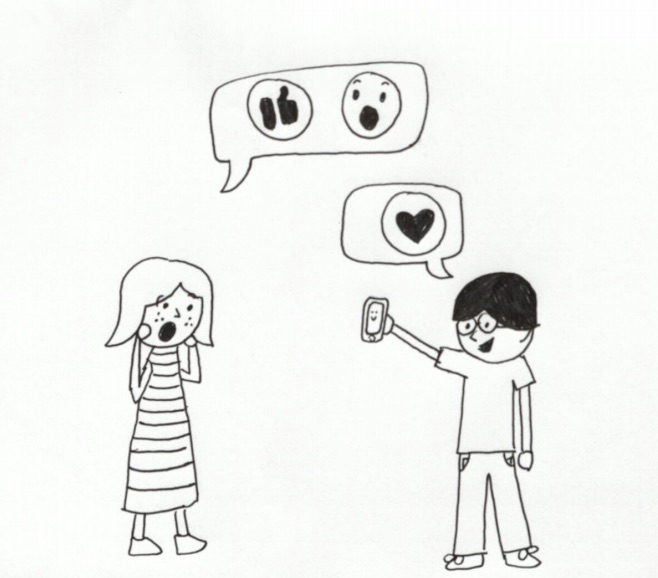

Perhaps to give an air of nuance to how its users can interact with content, Facebook recently introduced five new “reaction emojis.” Now users supposedly have more ways of telling others what they think, but to what extent this actually encourages thinking, as opposed to something else, is worthy of consideration. Almost every aspect of these new reactions seems to hinder the use of language, and by discouraging the way we express our thoughts, the actual act of thinking becomes discouraged as well.

Reactions are personal, and telling others how one feels usually requires some thought process, to find the correct way to express what one is thinking – which can now be bypassed with a single click.

Each reaction is represented primarily by a picture, not a word. The full spectrum of reactions to any given post is not immediately shown, only the three most popular reactions are. (Perhaps to encourage emotional bandwagoning? Who knows.) Finally, and this may be splitting hairs, but reactions are not normally given to something; responses are. Reactions are personal, and telling others how one feels usually requires some thought process, to find the correct way to express what one is thinking – which can now be bypassed with a single click. Also, who is Facebook to determine the different ways its users can respond to things?Who chose Like, Love, Wow, Haha, Sad, and Angry as the full range of reactions one can have?

The only options these new emojis expand are those for not thinking. Not to mention the data available to different media corporations, which they will undoubtedly use to see what exactly makes people Wow, Angry, or Sad. The art of clickbait is increasingly becoming a science, and based on the current political situation, it appears to be affecting more than just what we see and how we interact online. Even though groups that spend the most time on social media are particularly vulnerable to this effect, I’m confident that William and Mary, with its strong intellectual tradition, won’t contribute to this trend.