A diverse group of students, faculty and community members poured through the doors of the Commonwealth Auditorium Tuesday, March 23 to hear Haida artist and activist Robert Davidson give a talk, entitled “An Innocent Gesture.” Attendees kept arriving even after the talk began, filling nearly all of the seats in the auditorium.

The lecture was introduced by chemistry professor Carey Bagdassarian, who thanked the event’s sponsors, including the Center for the Liberal Arts, the office of the Arts and Sciences Dean, Reves Center for International Studies, American Indian Resource Center, American Indian Student Association and the Muscarelle Museum of Art.

This lecture was meant to tie into the theme of this year’s COLL 300 courses. Bagdassarian took the time to explain this new element of the College of William and Mary’s curriculum.

“The on-campus aspect of the COLL 300 class brings the world to William and Mary,” Bagdassarian said.

He said that each semester, the COLL 300 classes will focus on a particular theme, with this semester’s theme being unrest. Davidson spoke about his experience attempting to revitalize the culture of the First Nations Haida people in his hometown of Masset, British Columbia, Canada after many decades of oppression.

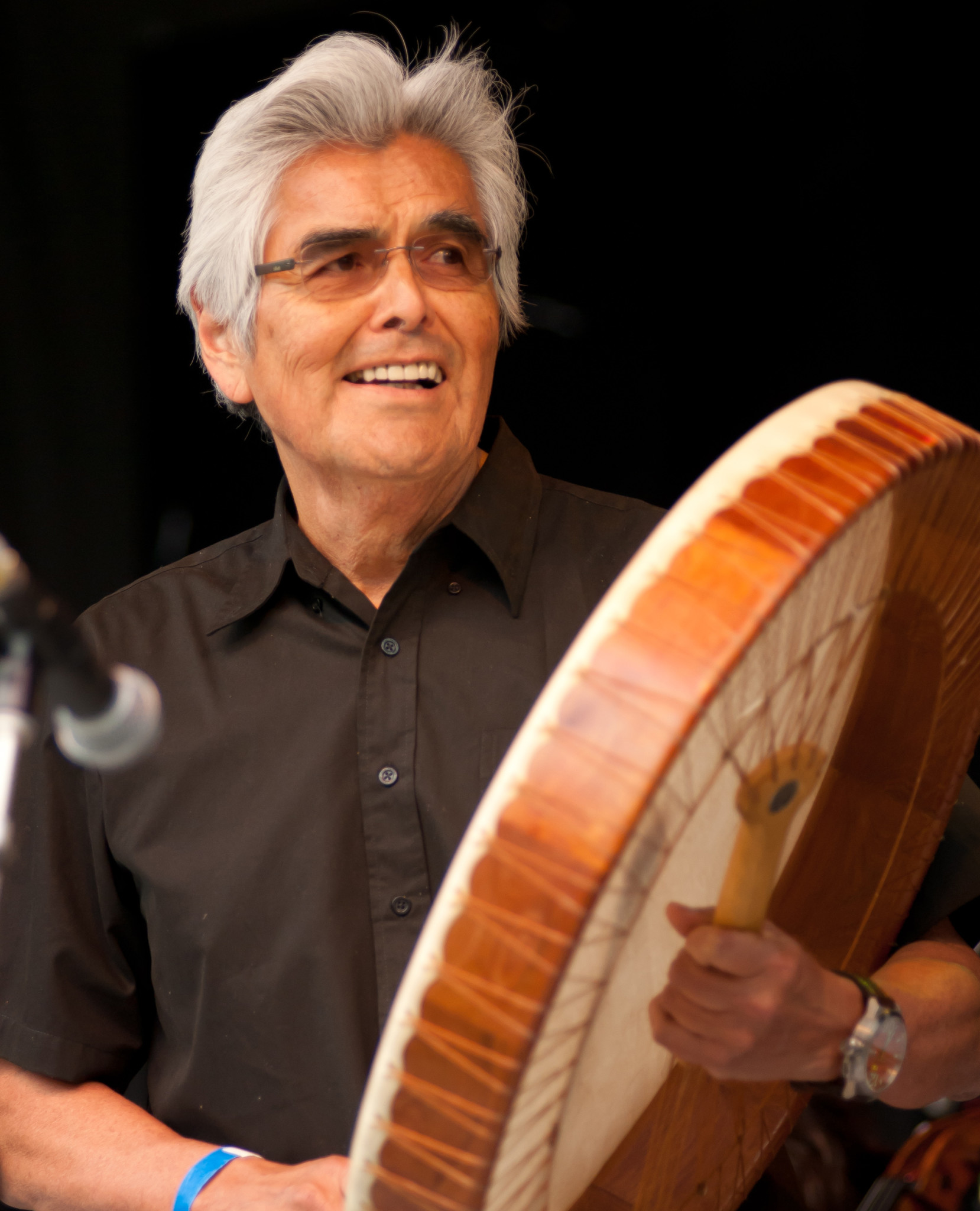

When he took to the stage, dressed in bright colors, speaking slowly and deliberately, Davidson showed personal photos of his family, friends and community. He shared the story of the time in his youth where he carved the first totem pole his town had raised since 1880.

He said that growing up he had very little knowledge of Haida culture, as his community was not allowed to practice their traditions. He felt a disconnect between himself and his ancestry, between the First Nations cultures he learned about in school, and what he observed when he came back home to his family.

“Every time I came home, I felt an emptiness,” Davidson said. “I felt an emptiness where my spirit was.”

Davidson said that he had a deep connection with the elders in his community, as he and his grandparents had a strong relationship. He said that after recognizing the “emptiness” for what it was — a disconnect with his culture — he decided to offer a totem pole to the elders. The totem pole would be a way for the community to celebrate its culture in a way that had been prevented for a long time because of injustices enacted against First Nations people.

He began to carve the first totem pole Masset had seen in decades. It was an ambitious project, and Davidson said he had some reservations when he first took it on.

“I didn’t want to look at the log at first; I was terrified of what I had committed to,” Davidson said. “But after asking myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I got tired of that question and said, ‘I’ll find out later.’”

After finding his own sense of determination, Davidson spent three and a half months carving the totem pole out of a massive log. According to Davidson, he received a large amount of support from his family, especially his grandfather, who helped him carve the totem pole even though he was nearly 95 percent blind.

“He cared so much about what I was doing; it really helped me maintain my commitment,” Davidson said.

He said his brother, father and other relatives helped with the carving even when they had other responsibilities to attend to. In particular, his father started to build a shed to house the totem pole while Davidson was carving it, but because it was fishing season, he didn’t have time to finish building it.

“On a rainy day we’d carve on the sheltered side,” Davidson said. “And on a nice day we’d carve on the exposed part.”

It felt like a championship game that we were winning. It opened the door for songs to be sung again, it opened the door for dances to be danced, and it was an incredible experience.

When the totem pole was completed, the community manually raised it together. According to Davidson, there was a crane in the village at the time and the crane’s owners offered to use it to raise the pole, but the elders elected to have the whole community raise the pole together instead, reinforcing the community-building and traditional aspect of the pole’s creation. He said that raising it manually added to the feeling of triumph that the community felt in the reclamation of their cultural traditions after years of oppression.

“It felt like a championship game that we were winning,” Davidson said. “It opened the door for songs to be sung again, it opened the door for dances to be danced, and it was an incredible experience.”

One of the talk’s sponsors was the College’s American Indian Student Association, which celebrated their second annual powwow recently. AISA Co-president Emily Williams ’18 said she was glad so many people attended Davidson’s talk and suggested that perhaps the audience was so robust because a number of professors had offered extra credit in their classes for attending.

She also expressed concerns about the lack of campus awareness about Native American issues more generally. She said that AISA is working to recruit more members and expand their events to increase awareness of the community.

“The biggest problem is getting an audience together,” Williams said. “We’re such a small group on campus and such an underrepresented group in general. It’s not so easy to garner interest.”

Williams said she was touched by the personal nature of the story Davidson chose to share in his talk.

“I found it to be a pretty intimate story,” Williams said. “I was pretty surprised. He went a lot into how his family helped him, a lot about what it meant to his community and how it changed everything. You could tell it meant a lot to him.”

Davidson closed his talk by answering audience questions about the story he told. He expressed his hope for the growing re-acceptance of Haida culture in his hometown and beyond, citing art, spirituality, song and dance as ways to both connect with and propagate culture.

“It strengthens our connection to our cultural past,” Davidson said. “And it creates a foundation for us to grow from.”