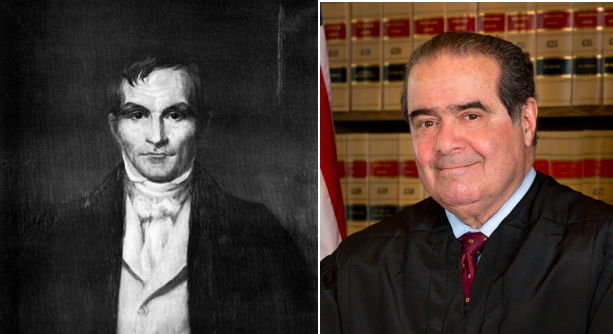

The unexpected death of United States Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has ignited a political brawl over who should get to fill his vacant seat on the bench. Arguing that the next president ought to nominate a justice to fill the vacancy, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has vowed to not hold confirmation hearings for President Barack Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland. There’s been a lot of talk of precedent on both sides.

Looking back in history, the career of Philip Pendleton Barbour, an alumnus of the College of William and Mary, mirrors some of the current national controversy. His own path to the Supreme Court was a somewhat rocky one, and his eventual death led to a brief but striking judicial fiasco.

So, who was Barbour? A native of Gordonsville, Va., he passed the bar in Kentucky.

During his brief stint at the College in 1801, he studied under law professor St. George Tucker.

Barbour’s political career kicked off after that. He rose from Virginia’s House of Delegates to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served as the Speaker of the House from 1821 to 1823. He espoused Old Republican views within the Democratic-Republican faction and was a strict interpreter of the Constitution.

Turning down an offer from fellow alumnus Thomas Jefferson to become a law professor at the University of Virginia, Barbour instead became a judge in the Virginia General Court. Eventually, he returned to the House, where he ingratiated himself with President Andrew Jackson by heralding states’ rights and promoting the legalization of slavery in western states.

In return for this support, Jackson appointed Barbour to the District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. His views also caught the attention of others within the party. In 1832, Southern Democrats nominated Barbour as an alternate running mate for Jackson, hoping to push New Yorker Martin Van Buren off the ticket. Barbour withdrew his name to preserve party unity.

It was this party loyalty and two Supreme Court vacancies that set Barbour up for his next career move. Chief Justice John Marshall (yet another College alumnus — are you sensing a theme here?) passed away in 1835. Justice Gabriel Duvall resigned that same year due to old age and growing deafness. Nearing the end of his second term, Jackson nominated Barbour to fill Duvall’s vacancy.

Critics in the Senate worried over Barbour’s state-centric, Jacksonian worldview and grew anxious that the nominee would undermine the federalist court of the Marshall years. Two attempts were made to delay the confirmation. However, on March 15, 1836, the Senate ruled in favor of Barbour and the new Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney (whose previous confirmation hearing had been delayed indefinitely). In total, Jackson appointed six justices during his tenure, two during the election year of 1836.

Barbour went on to serve for five years and hear 155 cases.

The last case he heard was United States v. The Amistad, which determined the fate of a group of kidnapped Africans who had mutinied and seized control of the Spanish slave ship “La Amistad.” When the ship drifted into American waters, the Africans were jailed. The Spanish government and pro-slavery advocates, including outgoing President Martin Van Buren, pushed for their extradition to Cuba. Abolitionists objected, including former president John Quincy Adams, who argued on behalf of the group. Eventually, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the kidnapped Africans.

Barbour did not live to see that decision. He died unexpectedly on Feb. 25, 1841, prompting a sudden recess in the hearings.

One day later, before Barbour was even buried, Van Buren nominated district court judge Peter Vivian Daniel as his replacement. Another Virginian with comparable political loyalties, Daniel had also previously succeeded Barbour in the district court.

Whigs in Congress moved to block the confirmation to ensure that their President-Elect, William Henry Harrison, would appoint the new justice instead. Daniel’s confirmation vote took place at midnight between March 2 and March 3. The Senate Whigs rallied but failed to block a quorum. Daniel won the confirmation, 22-5, on the very last day of Van Buren’s presidency. He went on to become a proponent of slavery on the bench and remained in his position until his death in 1860.

So, what should we take away from all this? I don’t know. It all happened a long time ago and this isn’t meant as a political screed either way. I just think it’s kind of interesting that someone from the College was mixed up in issues that mirror some of the disputes we’re still seeing today, like concerns over confirmation hearings and second term Supreme Court appointments.

Basically, nothing ever changes.

Great piece! There are so many great W&M stories out there. Kudos to Aine for finding this nugget.