This article contains references to suicide and self-harm.

Monday, March 29, Provost Peggy Agouris notified students at the College of William and Mary that pass/fail grading would not be expanded for the spring 2021 semester, despite outcry from students over added stress due to the pandemic. Three days later, Agouris made controversial remarks on mental health during her regular office hours, sparking further condemnation of the administration’s recent handling of student wellness.

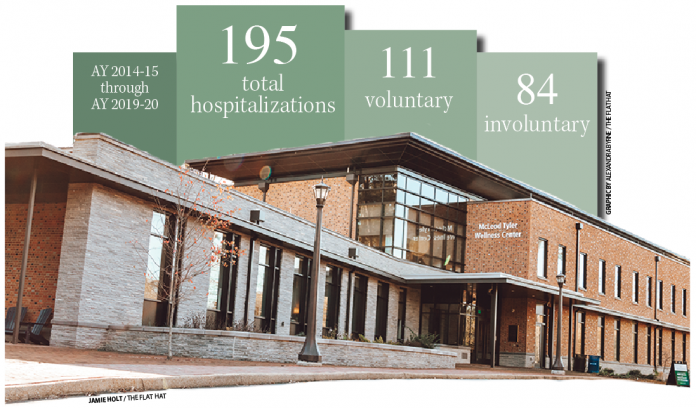

The subsequent conversation has led many to share their experiences with the College’s mental health services, revealing an overburdened counseling center and numerous instances of involuntary hospitalization for mental health reasons. According to records obtained by The Flat Hat, in the past six years, 195 students were hospitalized for mental health reasons, and 84 of those hospitalizations were involuntary.

College Spokeswoman Suzanne Clavet emphasized that the College has taken measures to respond to students’ concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The mental health and overall wellness of our students, staff and faculty are among the university’s top priorities,” Clavet wrote in an email. “The learning and emotional challenges of the past year have required us to respond in new ways. During the pandemic virtual resources and various support services have been added across the campus community. Current services include numerous remote therapy groups, as well as ongoing support groups and meetings. Additionally, a new health clinic was opened in conjunction with VCU Health Services just blocks from campus to further expand the care options for the community.”

Still, some students say these measures are not enough.

Casey Kim ’23 shared her experience with involuntary hospitalization in a widely circulated April 1 Instagram post, in response to Agouris’ comments. The process Kim underwent began with a care report — an online form in which students, faculty, staff or parents can report concerns with a student’s mental health or safety to the Dean of Students Office — which was filed by one of Kim’s professors.

“I was told by the Counseling Center that since I had a history of depression and suicidal ideation (I made it very clear that I wasn’t actively suicidal) my two options going forward were to take a leave of absence for the remainder of the semester or go to a mental hospital,” Kim wrote in her post on Instagram.

Kim was directed to the Dean of Students Office, which she said threatened suspension. With no stable home to return to, Kim said she felt trapped into making a decision with which she was uncomfortable.

“The last thing I was told by Dr. Felicia Brown-Anderson was ‘comply, comply, comply’ to get back on campus,” Kim wrote.

Director of the Counseling Center Carina Sudarsky-Gleiser said that the center advises compliance in line with the College’s Medical and Emotional Emergency Policy.

“I can’t speak to any specific cases or discuss particular treatment recommendations,” Sudarsky-Gleiser wrote in an email. “I can tell you that the Counseling Center provides clinical recommendations regarding need for further assessment or intensive inpatient treatment, in accordance to the William & Mary Medical and Emotional Emergency Policy (MEEP) and the Psychological Emergency Protocol (PEP), when a student exhibits high likelihood of harm to self or others and/or symptomatology that interferes with their ability to function independently on campus.”

The MEEP policy is intended to maintain the safety of the student and the community and is activated in the event of suicidal attempts or other “displays of manic or psychotic symptoms.” According to the MEEP, failure to comply with its procedures could result in disciplinary action under the Student Code of Conduct. Sudarsky-Gleiser said that the Counseling Center regularly informs students of the consequences of non-compliance.

“Counseling Center staff members will recommend a course of treatment that will help a patient address the presented mental health crisis and encourage a student to follow that recommendation,” Sudarsky-Gleiser wrote. “The Counseling Center may also remind a student that according to the MEEP/PEP, ‘failure to comply with the provisions of the university’s Medical/Emotional Emergency Policy may result in disciplinary action through the Student Code of Conduct.’”

But for students suffering from depression and anxiety, disciplinary action can only worsen the situation, Kim explained.

“Anyone who has suffered from depression can tell you that there is a lot of stress that comes from the feeling of being out of control of one’s own life and, as so-called mental health professionals, the Counseling Center should have been more aware of that.”

“Anyone who has suffered from depression can tell you that there is a lot of stress that comes from the feeling of being out of control of one’s own life and, as so-called mental health professionals, the Counseling Center should have been more aware of that,” Kim wrote. “William and Mary took away my personal autonomy by forcing me into a mental hospital. They lied to me about certain accommodations and amenities that would be available to me upon admission.”

Sudarsky-Gleiser emphasized that the Counseling Center has an obligation to connect students with further resources, including potential hospitalization, if it is deemed necessary.

“There are many treatment options, but yes there are circumstances where Counseling Center staff would recommend a patient seek additional treatment through a psychiatric hospital or refer them for additional evaluation at the ER,” Sudarsky-Gleiser wrote. “Mental health professionals have the ethical and legal duty to save a life and ensure that the people they serve are able to provide for their basic human needs. In instances in which a student discloses information indicating substantial likelihood of risk to themselves or others, a referral for additional evaluation at the ER or a voluntary psychiatric hospitalization for intensive mental health treatment is recommended.”

According to Sudarsky-Gleiser, there are nine different service recommendations that the Counseling Center might make for a student with depression or suicidal thoughts. Several involve therapy — whether it be at the Counseling Center or via an off-campus provider for longer-term therapy. The College may also recommend psychiatric services within the community, intensive outpatient therapy or intensive treatment in a specialized treatment center. The Counseling Center is also able to refer students to the Student Health Center to explore potential antidepressant medication. Lastly, the center can recommend a voluntary medical leave, voluntary hospitalization or an Emergency Room evaluation. In the case of an ER evaluation, the possible results are either ongoing outpatient therapy, voluntary hospitalization or a Temporary Detention Order.

TDOs are legal documents that require immediate hospitalization for one to three days, during which a hearing is held to determine further action. Costs for hospitalization under TDOs fall upon the patient.

“There are situations in which the level of risk for a student (or any person assessed at the emergency room) fits the ‘substantial likelihood of harm to self or others,’ the student is unwilling to voluntarily follow the recommendation for a psychiatric hospitalization and there is not an available less restrictive alternative,” Sudarsky-Gleiser wrote. “In these cases, the ER pre-screener would request a hearing by a magistrate who may order an involuntary psychiatric hospitalization.”

TDOs are the only path in which a student might be involuntarily admitted to a hospital, yet over 40% of hospitalizations since the 2014-15 academic year have been involuntary. The Pavilion, one of the facilities at which students at the College are hospitalized, describes the TDO process as an extreme measure.

“Taking away a person’s freedom and committing them to psychiatric treatment against their will is an extreme measure that it is only undertaken when all other treatment options have failed or been deemed unsuitable,” the Pavilion’s website says.

In the past, the majority of students at the College who were hospitalized for mental health reasons were admitted to either the Pavilion or Riverside Behavioral Health, along with various other hospitals outside the community. Recently though, several students have been sent to the Virginia Beach Psychiatric Center. In a Sept. 23, 2020 email obtained by The Flat Hat, Mental Health Services Coordinator Christine Ferguson suggested students at the College experienced poor COVID-19 safety protocols in existing facilities.

“We just had a bad experience with another hospital and COVID policies and I think we would like to do direct admissions to VA Beach if possible,” Ferguson wrote to VBPC Community Liaison Sarah Becker. “I wanted to know what the policies are regarding COVID/PPE on the unit. Do staff where masks? Washing hands? Just curious if you are able to share. This recent experience was really bad. Just even curious what the guidelines for psychiatric facilities are.”

During the 2019-20 academic year, four students were admitted to Pavilion, seven were admitted to Riverside, two were admitted to VBPC and nine were admitted to other Virginia hospitals. Upon request, the College did not reveal to which facility the email refers.

“William & Mary was an early adopter of strict COVID protocols including the wearing of face masks indoors and out,” Sudarsky-Gleiser wrote. “Not all of our community partners for inpatient psychiatric care have been equally aligned. In cases where partners have loosened their practices, we have sought resources that more fully match our protocols.”

The College said it does not currently hold a contract with VBPC, however, it is in the process of drafting memoranda of understanding with several facilities.

“The university does not have an agreement in place with the Virginia Beach Psychiatric Hospital,” University FOIA Officer Lillian Stevens wrote in an email. “The university is in the process of implementing MOUs with existing and new partners providing psychiatric hospitalization, we expect that process to be ongoing through the summer and won’t have a current document to provide until that process is complete.”

Not all Counseling Center processes end in hospitalization — over the past 10 years, the center has made 772 referrals to the Student Health Center. Over 365 students have had an appointment with the College’s psychiatrist since 2016. Last academic year, the Counseling Center referred 53 students to the mental health services coordinator for a subsequent referral to psychiatric services.

Still, students say the College’s mental health services are lacking, citing inability to obtain counseling appointments and excessive bureaucracy following a crisis. Andrew, who wished to be referred to by his first name alone, is a student at the College who was unable to make an appointment with the Counseling Center upon first arriving in August of his freshman year. By the time of his first appointment Oct. 28, it was too late. In late November, he attempted to take his life.

“I feel like it’s a no brainer if someone is coming to campus having previously needed therapy to do your part in helping them get therapy established in the place that they’re living, especially since we’re paying them money to do all these things,” Andrew said. “I had told the College before coming that I had diagnosed anxiety and depression. My point is they had the information and they put out a questionnaire to all students that are coming in — it feels like they don’t do much with that information unless you actively go out. And for a lot of people with depression, that is the hardest part.”

Since his first year, he has settled into therapy and has met regularly with Care Support Services. But additional meetings have been a burden to balance with academic work and extracurricular commitments.

“They’re very appreciative of the time I take out of my week to come meet with them,” Andrew said. “I don’t quite know how productive they understand the meetings to be. I think they think it has value, and to some degree it does. But at some point it loses value. When I’m two years out of the event, still in therapy, have no volition to leave therapy, I don’t need to meet with them on a monthly basis. And I don’t think they acknowledge that.”

Andrew said systemic change is needed to address the issues that plague the College’s mental health services. He emphasized the need for preventative and proactive measures. If the College chose not to extend the pass/fail grading policies for this semester, he said, it should have provided other concrete actions to reduce stress and anxiety during the pandemic.

“A lot of the administration’s mental health policies are reactive, which in my case was way too little, too late,” he said. “If they don’t start taking proactive steps towards addressing mental health issues, things won’t improve.”

Thank you for shining a light on this problem. It is not only at W&M, but most campuses today. Students deserve better than what they are getting from the administration. It is clear their priority is to protect the institution first and patient care falls somewhere much farther down on their list.