In November of 2013 the Patriot-News of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania issued the following apology and retraction: “In the editorial about President Abraham Lincoln’s speech delivered Nov. 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, the Patriot & Union failed to recognize its momentous importance, timeless eloquence, and lasting significance. The Patriot-News regrets the error.”

The Gettysburg Address was panned by the then-Patriot & Union who, no fans of President Lincoln’s, called it “silly” and deserving a “veil of oblivion.”

Despite the time that’s passed, the Patriot-News editorial board made the decision in 2013, more than 150 years after the article was published, to issue a retraction and apology; doing so with the knowledge that their small readership would likely neither care nor have any knowledge of their previous transgression. “The world will little note nor long remember our emendation of this institution’s record,” they wrote, “but we must do as conscience demands.” The Patriot-News that day chose the right honorable duty of true journalism.

Journalism is, in one sense, an active referee in and of our daily lives. It is easy to think of the larger accomplishments that occupy the American mythological landscape of journalism and journalists. What often is overlooked or forgotten is the work after a story is published; what happens when the headlines get it wrong.

News organizations big and small mess up and fess up all the time in big and small ways. Corrections run on page A2 in print for many and alerts run online. But how often are those noticed? How often do you actively search for corrections and updates to the news you’ve already read? Reading an article in the morning, you can come away with a different understanding than someone who reads that article that afternoon.

Famously, The New York Times has been accused of “stealth editing” certain articles (but are far from the only ones). Stealth editing is a term used to describe when a news company edits an article online and does not note the change. More derisively, it is a term used to shout journalistic malpractice. There are plenty of unmalicious reasons to edit an article after online publication: spelling errors or things deemed by the higher ups to be editorially insignificant (whatever that means).

Stealth editing and its slippery slope should worry readers as much as it does me. Kalev Leetaru writing for RealClearPolitics conveyed the magnitude and severity of the problem well, writing, “Far from an isolated deviation of accepted journalistic practice, stealth editing has become the norm in digital newsrooms from small local outlets through the nation’s most prominent papers. In the web era, even our papers of record are being edited on the fly, permanently changing the concept of historical record from the immutable ledger of the past to a real-life Memory Hole. George Orwell had it right.”

The Flat Hat has a long-standing policy that any change to an article be noted and solely considered a “correction.” As the Associated Press, from whom we derive our standards, puts it: “A correction must always be labeled a correction in the editor’s note. We do not use euphemisms such as ‘recasts,’ ‘fixes,’ ‘clarifies’ or ‘changes’ when correcting a factual error.”

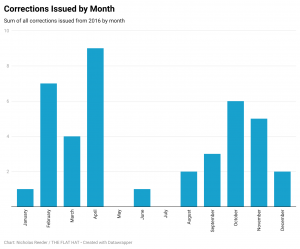

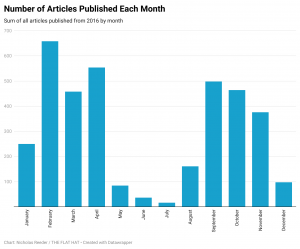

Since January 1, 2016 the Flat Hat has issued corrections on 41 articles. Roughly 60% of those were factual corrections. This is not that surprising as most things that need correcting are factual: names, dates, information, updates. As such, most corrections — 28 in fact — are in the news section. The remaining 40% was split evenly between updates to quotes and clarifications to articles. The number of corrections is almost perfectly correlated with the number of articles published, month by month and year by year.

An example from the past few years of Flat Hat corrections include:

“Correction: This article has been corrected to reflect that a quote from Rabbi Gershon Litt had been previously attributed to Hillel President Alexina Haefner ’19. It has also been corrected to reflect that Haefner was misquoted as saying she had been warned by her mother about the hate she would face after converting to Judaism.”

And a personal favorite:

“Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly replaced the word “millenial” with “snake person” in a quote from Ben Lambert ’19. This was due to a satirical word replacement browser extension installed on the news editor’s version of Google Chrome and not an implication that 38 percent of Williamsburg residents are reptilians.”

Typographical mistakes, copy-editing errors, mishearing someone, misunderstanding a situation or person, doing the math wrong. These are all real problems that happen and need to be corrected. However, there must also be a balance between corrections and standing behind your reporting. Receiving an email from a disgruntled reader is not sufficient for a correction, though we may want to look into the matter anyway. Hearing from someone with knowledge and corrections is crucial to forming a positive and trusting relationship with the community that we serve. It is also crucial that we then act on those relationships and that information.

The Flat Hat — in just the past year alone — has had to make those judgement calls, balancing integrity and accountability. With some frequency, various editors and writers will receive emails calling for a retraction or correction for an article. Oftentimes these are valid points and the section editors perform their task dutifully, updating the article online and issuing the correction. Other times, however, these emails demand action on behalf of an interested party that The Flat Hat correct or retract a story on their say-so. This does not qualify for a correction or retractions and results in no action.

What I fear is that somebody will read a story once and then report a falsehood, whether or not they know it to be so, before the correction is issued. This is why it's important to get it right the first time. As Mark Twain apocryphally said, “A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots” (Don’t worry, the irony of this quote does not escape me).

Matt Lowrie ‘22 is the Flat Hat’s inaugural Standards and Practices Editor. He enjoys reading and commenting on but not actually writing the news. Email Matt at flathat.ombuds@gmail.com or submit a formal comment or complaint here: https://forms.gle/nr7VfHSVCtqqh8i59.

Data Editor Nick Reeder '23 contributed data analysis and charts of this opinion.

CORRECTION: 10/5/21 An earlier version of this article contained a typo "...replaced the word “snake person” with “snake person” in a quote..." It has been updated to say "...replaced the word “millenial” with “snake person” in a quote..." correcting the error both in this article and the original. The total corrections have been updated from 40 to 42. Updated article with charts and clarified Nick Reeder's role.

The irony of this correction does not escape the author.