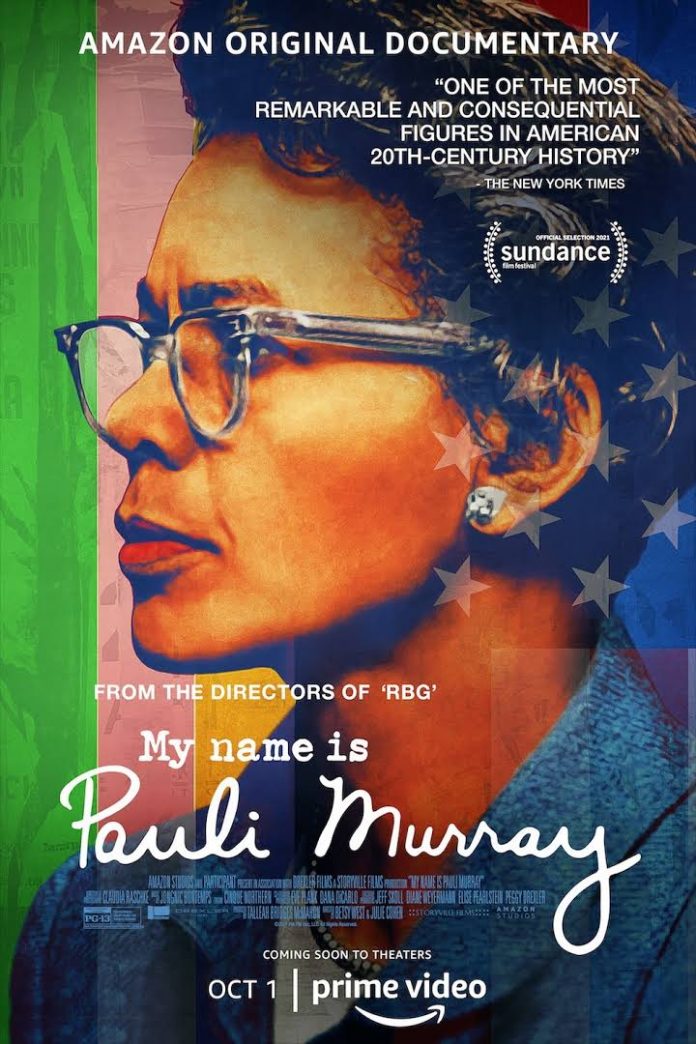

On Wednesday, Oct. 6, the Gender, Sexuality & Women’s Studies Program organized a screening of the documentary “My Name Is Pauli Murray” in Tucker Hall. Pauli Murray was one of the most consequential civil rights activists and lawyers of the twentieth century, whose work informed the Supreme Court’s decisions outlawing sex discrimination. As a queer Black woman, Murray – who shifted between feminine and gender-neutral pronouns – coined “Jane Crow” that emphasized the double bind of racial and gender discrimination.

The GSWS Program also hosted a panel discussion after the screening. The three panelists were Diya Bose, Assistant Professor of GSWS/SOCL, Vivian Hamilton, Professor of Law and Rev. Charles Bauer, Chaplain, Episcopal Church at William and Mary. The panel discussed Murray’s perseverance through white supremacist institutions while wrestling with her own gender identity.

“Pauli has been so critical to so many of the rights and freedoms that we all enjoy,” Brittney Cooper, a professor at Rutgers University-Brunswick, said in the film. “And most of the time, my students are like, ‘Why don’t we know more about Pauli Murray?’”

The documentary intersperses interviews with prominent scholars and activists with Murray’s letters, diaries, poems and manuscripts. Together, they paint a complex portrait of Murray as an individual unafraid to challenge dominant systems of oppression despite repeated setbacks.

Murray’s civil rights activism kicked off when they protested a segregated bus in Petersburg, Virginia in 1940, fifteen years before Rosa Parks did the same in Montgomery, Alabama.

“What they were fighting for was the right of Black people to easily assimilate into the whole of American life,” Cooper said in the film. “But the judge knows that this is becoming a big deal, and so, ultimately, they get outmaneuvered. The judge drops the segregation statute here that’s at play and just says, ‘Y’all were disturbing the peace.’ So they are not able to reframe legal precedent.”

Instead of backing down, the judge’s dismissal emboldened Murray to push back harder against injustice.

“At the time, I felt only the bitter disappointment of a personal defeat,” she wrote in her diary. “But I began to sense that we were a small part of a teamwork effort which envisioned the ultimate overthrow of all segregation law. The thought was stupefying.”

The other turning point in her career came when she attended Howard University’s School of Law as the only woman in her class. The rampant sexism of the faculty led her to develop the theory of Jane Crow, a reference to the Jim Crow laws of the South that legitimized racial segregation, which posited that sex discrimination against Black people was equally severe and systemic.

“Despite being one of the most highly-trained lawyers, Pauli can’t get in the door in a New York law firm,” Patricia Bell-Scott, author of Firebrand and the First Lady, said in the film. “She finally set up her own firm, and one of the most painful experiences was her going into court to represent a client and having a witness identify Pauli as the prostitute because of course she couldn’t possibly be the lawyer.”

Despite Murray’s erasure from America’s legal milestones, many interviewees emphasized their irreplaceable role in advancing the battle for civil rights.

“Pauli conceptualized so much of what the legal architecture has been for challenging systems of discrimination,” Chase Strangio, ACLU attorney, said in the film. “We can’t comprehend legal movements for justice without understanding Pauli’s role in them.”

For example, in Murray’s later career, they published the article “Jane Crow and the Law,” which ignited a new debate about sex discrimination vis-a-vis Jim Crow laws. The article’s tenets would later be cited by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the 1971 Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed.

“We were saying the same things that Pauli had said years earlier at a time when society was not prepared to listen,” Ginsburg said in the film.

Away from public view, Murray grappled with their expansive gender identity and even believed that they possessed concealed male genitals. In correspondences with various doctors, Murray expressed confusion, paranoia, anger, sadness and disappointment.

“Pauli’s historical records allow us to consider the humanity of someone who was Black and gender non-conforming in the time that Pauli was living,” Raquel Willis, writer and activist at Ms. Foundation, said in the film.

Taken as a whole, Murray’s complex identity yet substantial career achievements inspired a sense of awe from the panelists but also anger at her mistreatment and frustration with her erasure from historical accounts.

“There’s this audaciousness, but there’s this deep sense of restlessness and trying to prove that they were good enough,” Professor Bose said. “And that frustrates me.”

Moreover, the way we talk about Murray today is still heavily informed by racial hierarchy and gender discrimination.

“The way in which the documentary carried through this theme of Murray being ahead of their time struck me as wrong,” Professor Hamilton said. “I see the way that I have interpreted and the way that I see Murray’s ideas and theories being used as ideas that were of their time. But because Murray was Black, because Murray was a woman, I think the intersectionality of that, the fact of being an outsider, relegated her to the background.”

Reflecting on the documentary, Yuqing Wang, a J.D.‘23 student in the law school, found Murray’s late-career pivot to the Episcopal Church fascinating.

“I was stunned at first to see that she ended up in religion since I’m an atheist myself and didn’t really understand the choice,” Wang said. “But then I started to recognize that a ‘sense of belonging’ has been the subject of her transitions and struggles, which include both race and gender, two of the most prominent themes of her legacy.”

Anas’a Dixon, a J.D.‘22 student in the law school, identified erasure and diminishment as some of the key themes.

“One line that struck me was when Murray applied for tenure and the board responded that their conceptualizations ‘lacked brilliance’ or when her classmates at Howard Law laughed at them when they presented their legal approach to dismantling ‘separate but equal’,” Dixon said. “I am struck by this continuous pull between them living and approaching certain topics so boldly and keeping others so very private and the efforts to erase their impact.”

Murray’s profession was a lawyer throughout most of their life, but feminism played a central role too, and this could have been further explored.

“Something I wish the documentary had discussed further was Pauli’s relationship with the feminist movement,” Tess Goldenthal ‘24 said. “Although Pauli most likely today would’ve identified as non-binary or transgender, though I don’t want to make assumptions, I learned in my Women of Color Feminisms course that Pauli started to embrace feminism later in their life in order to fight back against the oppressive system of sexism … and racism. I think this would’ve been a really interesting addition to the documentary.”