No matter what you do with yourself these four years at the College of William and Mary, chances are you’ll spend a good deal of time writing term papers. No one enjoys writing them, and some may condemn them as outdated and formulaic, but they serve valuable functions. They force you to make connections, to write, and most importantly, to think.

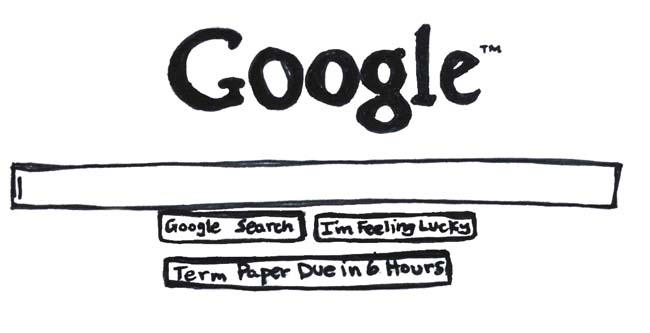

Any lengthy term paper requires research, which usually calls for more than a simple Google search. Even with the databases Swem provides, relevant sources aren’t always easy to find. And even when you do find sources, you have to wade through all the information you don’t need to get to the information you do need. Then, you have to figure out how it all fits together and craft an argument around your findings. All of this requires critical thinking. In order for your paper to be focused and make sense, you have to write clearly. After all, whether someone can write well is one of the best indications of whether he or she can think well.

Granted, the standard research paper does have its flaws: the format — topic sentence, thesis, body and conclusion — can produce trite, cliched papers of little significance. It also encourages plagiarism; when students aren’t given enough incentive to inject their own unique voices into their papers, which is often the case, they may use someone else’s. This puts the responsibility on professors to create genuinely engaging assignments and provide quality comments, as well as on the students to write original papers of actual value.

We can debate the practical use of writing, say, a six- to eight-page research paper on Aboriginal civil rights. (Not to minimize the plight of the Australian Aborigines — that just happens to be the last term paper I wrote). Citation styles, fonts, page margins — these things matter less outside the world of academia. And essay writing is not likely what the typical graduate from the College will be doing as a member of the work force. However, business, science and law majors, just to name a few, will likely find themselves doing plenty of written analysis in their jobs. For instance, how will epidemiologists working for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention be able to inform policymakers during a pandemic if they can’t properly explain their findings?

For those of you with the ambition to become millionaire CEOs, good luck communicating with your employees and shareholders if you can’t write effectively.

Even if your future profession doesn’t require writing skills, it will require you to think — at least, any job worthy of a College graduate will — and any decent term paper does the same.

Email Matt Camarda at mjcamarda@email.wm.edu.