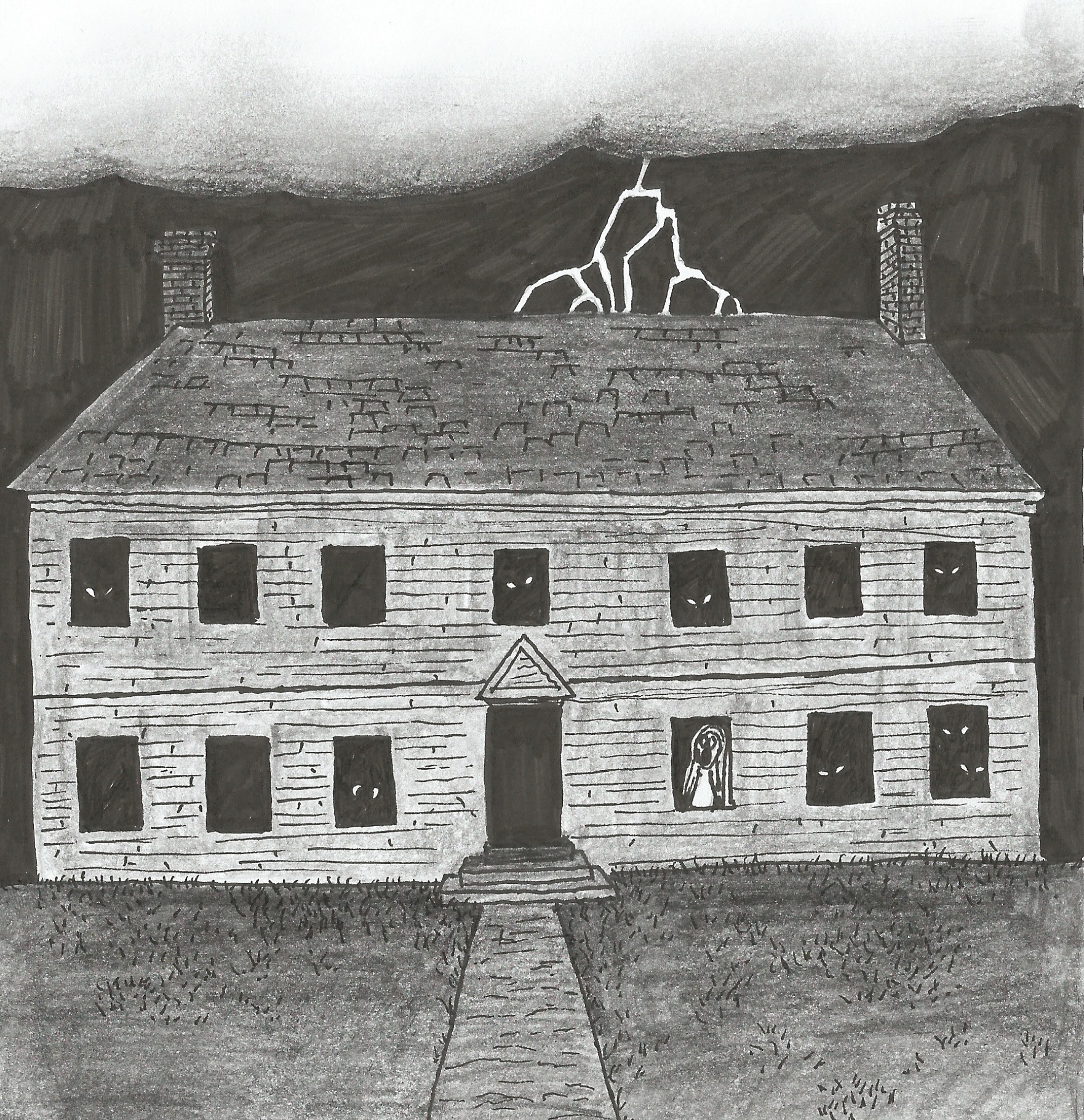

It’s hard to miss that blood-red house in the heart of Colonial Williamsburg. Those dark windows seem to follow you as you walk by, as if the house itself is watching. This is the Peyton Randolph House, one of the most haunted places in the United States.

“That house has a heavy feel — a dark vibe,” Original Ghosts of Williamsburg Candlelit Tour guide Clare Britcher said. “Guests on our tours often get some pretty wild pictures there, or actually sometimes see things. I have seen some really weird things there myself, including what I would call ghosts or spirits.”

Local author L.B. Taylor has written extensively on paranormal activity in Virginia. He believes that the Historic Triangle is haunted because of its history during the American Revolution.

“There are a lot of old houses here, a lot of trauma tied to the area,” Taylor said. “Some experts associate that with the spawning of spirits. This is one of those areas where, if there are such things as ghosts, they’re here.”

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Historian and Associate of the Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture Dr. Taylor Stoermer explained that this tragic past likely gave rise to the Peyton Randolph House’s supernatural reputation.

Relatives of Thomas Jefferson, the Randolph family, purchased the home in 1721. In a few years, the house became the deathbed of prominent Virginian Sir John Randolph. The only colonial-born Virginian to ever be knighted, Randolph was an early alumnus of the College of William and Mary.

“Sir John must have had stomach cancer; that’s what the symptoms looked like,” Stoermer said. “He lingered for a month. They’re bleeding him, they’re sweating him — we’re talking 18th-century medicine. He spent a month in agony before dying.”

Death visited the house again during the smallpox epidemic of 1748. According to colonial-era records, four of the house’s 23 residents succumbed to disease. Most of the dead were likely servants and slaves.

Today, the house is associated with many violent deaths. A frantic, elderly woman is said to haunt it. Known as “the shrew,” she warns visitors of impending disaster. Many locals consider the house to be inhabited by a more sinister, violent specter as well. Tour guides often warn groups not to go anywhere near the home at night, lest they incur the wrath of this violent phantom.

Original Ghosts of Williamsburg Candlelit Tour guide Heidi Hartwiger agrees that the house is weird. A few years ago, many of her colleagues reported the glass in their lanterns was cracking in front of the house. On one occasion, a fifth grader on a tour took pictures that seemingly revealed the image of a woman with a large black cat.

“I asked around and conventional wisdom was that it was Mrs. Peachy, [a former owner of the house],” Hartwiger said. “She was known for her big black cat. Rumor has it that she had many children, in addition to the one who died and an adopted one who died. When she misses her kids, she comes out to be with children.”

Family is what ultimately seems to haunt this house. Stoermer explained that, despite their diverging politics, Sir John Randolph’s two sons John and Peyton remained extremely close throughout the brewing tension that culminated in the Revolutionary War.

“Peyton often looked out on his brother’s house, which was on South England Street, about where the Lodge is now,” Stoermer said. “That house had been built at a slight angle so that its front door would face Peyton’s front door, rather than the Magazine, and they would keep lights on in the windows as subtle messages to one another.”

However, the house would become deeply divided. Peyton — who had no children — influenced the politics of his patriotic nephew Edmund, much to John’s disdain. Peyton would become the first president of the Continental Congress, while loyalist John would depart to England for safety.

In an emotional letter, John begged his estranged son to accompany him. Edmund refused, leaving his family in order to serve in George Washington’s army. John would eventually die in England, never to see his son or brother again.

“John’s last wish was to be buried in Williamsburg,” Stoermer said. “His daughter and son-in-law brought his body back. Talk about ghosts — the family left in 1775; they returned in early 1784. The town’s been destroyed. The President’s House has been burned down. The Governor’s Palace is burned down. Everybody’s gone. The town has been ripped apart by the war. Their house is in bad shape.”

In a lonely nighttime funeral procession, remnants of the once-mighty Randolph clan accompanied John’s body down DoG Street. John was laid to rest beside his father and brother in the crypt beneath the Wren Chapel.

Only in death would the broken Randolph family be reunited.