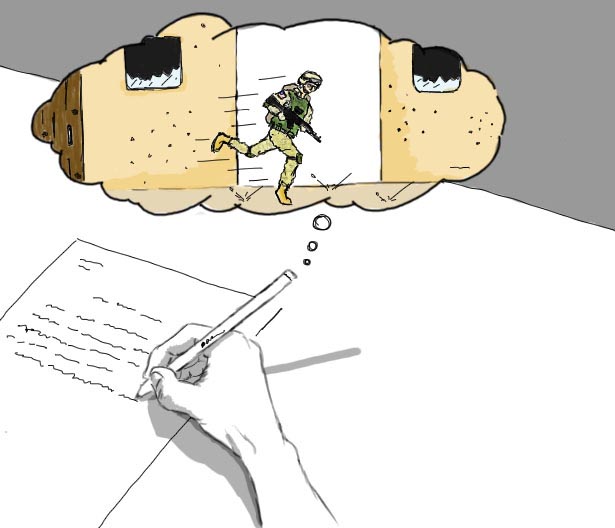

To tell a story is to be human. The reasons we tell and listen to them are nearly as diverse as the stories themselves: to be entertained, to worship, to glorify, to feel, to pass on, to improve ourselves. There is something instinctual about wanting to gather around the proverbial campfire. On Dec. 7 and 8, the Mason School of Business will host the Veteran’s Writing Project, providing a medium for servicemen and women to talk about their experiences. This should be of immense benefit to veterans and non-veterans alike, because storytelling facilitates acknowledgement and connection, which untold traumatic experiences can severely damage.

When we listen to people talk about experiences foreign to our imagination and perspective, we realize that personal history is itself a kind of diversity. It may not be part of our conventional conception of diversity, and it can be the least visible kind, but it informs one’s character to such a great extent that it is impossible to ignore. A veteran may not have returned home physically wounded, but he or she may be scarred by experiences that prevent re-adjustment to civilian life. We cannot begin to understand their struggles unless we allow them to speak openly, without judgment.

Speaking honestly about painful memories can let people ground themselves. In cases of post traumatic stress disorder, people have difficulty coping with reality and separating their present selves from past traumatic events. Staying silent keeps people from being seen, but causes alienation. Sharing with those who have had similar experiences can be a powerful act of validation. It will not erase the memories, but it will show people viscerally that they are not alone — that they do not have to face themselves alone. Perhaps, this can be the first step of a long return journey.

A medium for veterans to communicate their stories also serves a valuable purpose for non-veterans and families of veterans. Having little basis for understanding, our efforts to provide comfort and normalcy for veterans may be inadequate. If we do not know what they went through, how can we help them? Listening is essential; we can never have their experiences — that is our limitation — but we can be necessary witnesses to their fights, which they may not even be fully aware of, and potentially bear part of their burden. It also shows them we value what they have done and who they are. To honor is to listen.

As writers, we know that storytelling can empower; our job as a newspaper is to be a prominent platform for people’s stories. To let those stories go untold would be neglecting our duty to the College of William and Mary. While a different kind of platform, the Veterans Writing Project can empower veterans by making their experiences coherent and visible. This visibility can strengthen the connections between veterans, their families and their communities, increasing awareness of problems facing veterans and initiating a process of healing.

Hopefully, the Veterans Writing Project will successfully bring together veterans and non-veterans with unique perspectives and become a permanent part of the College campus.