Imagine sitting in class one day and discovering that you have a rough patch at the back of your mouth. Now, imagine it is three hours later and you notice the rough patch has moved.

Biology professor Jonathan Allen of the College of William and Mary has been in that situation — and he knew exactly what was happening. Allen is approaching the one-year anniversary of the discovery and removal of a parasitic worm from his mouth.

He initially discovered the worm at the beginning of the fall 2012 semester. Allen noticed a rough patch in his mouth that would move around throughout the day. He wasn’t sure what it was until he was giving the final exam to his Invertebrate Biology class.

“I felt this sensation in my mouth that had been happening but not in a place I could see it,” Allen said. “In the middle of the exam, though, it finally moved to the front of my lip.”

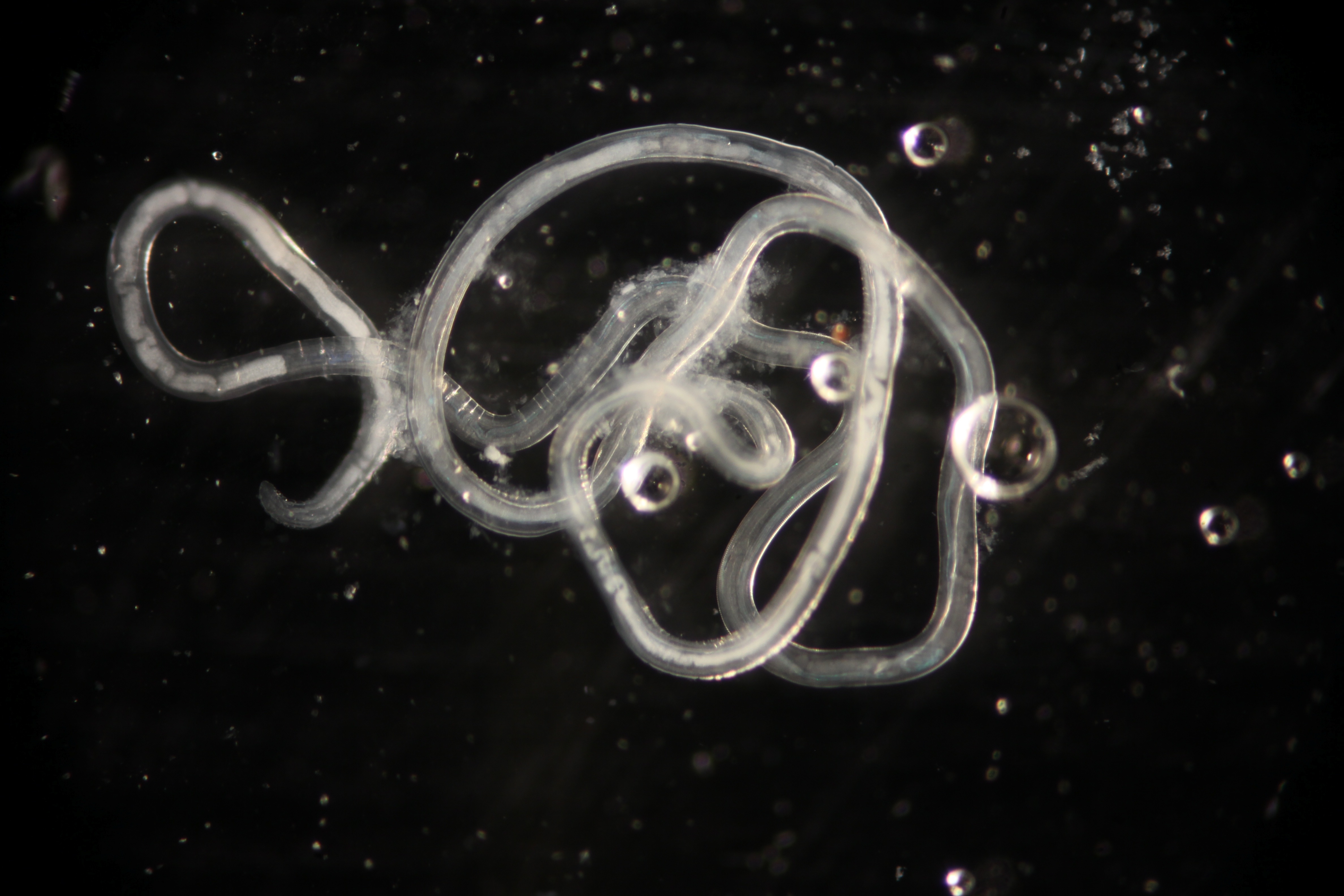

After the exam, he ran back to the Integrated Science Center to take some pictures of the newly discovered parasite. He quickly narrowed the parasite down to a particular worm: Gongylonema pulchruma.

“It was very exciting once I could actually see it,” Allen said. “When I saw the sinusoidal curls of it, I knew it was a nematode. When I looked into it, there [was] basically only one kind of worm [of this phylum] that it could be. Turns out there are very few worms that can live in your mouth.”

After Allen discovered the parasite, he called his doctor who referred him to an oral surgeon.

“I went there and brought papers and pictures of the worm as well as myself with the worm still in my lip,” Allen said. “I thought I was pretty convincing.”

However, the doctor’s opinion was different from what Allen envisioned.

“He looked at papers, he looked at the pictures, he looked at my mouth and basically told me that he didn’t see anything,” Allen said. “He simply brushed it off as a normal discoloration of the mouth.”

Allen began arguing with the doctor that the worm was actually there, but he soon left the office disappointed and frustrated. Not only did he feel that the parasitic worm was an interesting find, but he thought that it was something that needed to be reported.

After being woken up at midnight by one of his sons, Allen noticed the worm was at the front of his lip again and decided to remove it right then by himself.

“I grabbed these fine-tipped forceps, a scintillation vial, filled it with alcohol and had my wife hold the flashlight in the mirror while I pulled out the worm,” Allen said.

At this point, Allen knew he was correct, but he didn’t want to lose his proof – the parasite.

“My worst fear was that I would pull it out and drop and swallow it and it’d be gone and nobody would believe me,” Allen said. “I got it out on the third try, dropped it in the vial, and came over to [the College] still in my pajamas and started taking pictures.”

Between his visit to the doctor and his removal of the worm, he had emailed his neighbor, a professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School who works with nematodes. Allen gave her the worm to run tests and confirmed that it was, in fact, Gongylonema pulchruma. They then proceeded to write a paper and publish it in a medical journal.

Allen still has the worm in his refrigerator at the lab. He and his neighbor are planning on doing a full genome sequencing of the worm.

“We’ll have the whole genome of it so that other people could compare different genes to this organism,” Allen said. “It’s actually pretty abundant in livestock, so those worms have been sequenced before, but never one that was found in a person. So we can compare it to the ones that we think are the same species.”

Allen thinks that many people may be hosts to this parasite and not even know it.

Allen and the professor from EVMS received a grant to run tests on the source of the parasite. They concluded Allen probably received it from eating or drinking something with bug particles.

“You don’t have to go to, like, Mongolia and eat a rare insect dish to acquire this,” Allen said. “Anybody could have it.”

He offered some advice to rising pre-med students, as a result of his experience.

“When I talk to students, I talk about two things,” Allen said. “One: There is a lot about the world we live in that we don’t understand. Two: keep an open mind. There is a tendency, and I’m as guilty of this as anyone, to just stick with what we think we should see. It’s critical to be willing to be surprised and to not dismiss it when something unusual happens. I thrive on being surprised.”