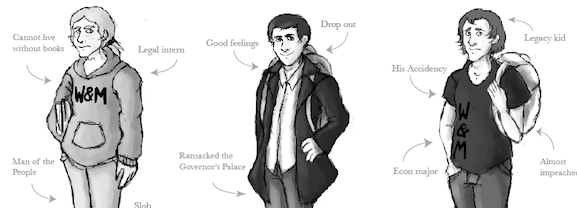

Thomas Jefferson

Declaration of Independence author, founding father and third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson wasn’t always impressed with the College of William and Mary — he even nicknamed Williamsburg “Devilsburg.” Nonetheless, Jefferson’s experience at the College made a massive impact on the young scholar’s fledgling political views.

He first arrived in Williamsburg as a 16-year-old in 1760, leaving his childhood home of the Tuckahoe Plantation in Albermarle County, Va. Law professor George Wythe quickly took Jefferson under his wing, even hiring him as a law clerk. At the College, Jefferson read John Locke and Isaac Newton, studied French and developed a passion for the violin.

The teachings of natural philosophy professor William Small also molded the student’s interest; Small introduced his pupil to many pivotal Enlightenment writings. Jefferson became close friends with John Page and lived in the College Building — today known as the Sir Christopher Wren Building.

According to legend, he was sometimes known to study in his room for 15 hours at a time — cramming, no doubt. When he wasn’t studying, Jefferson was known to hang out at the Governor’s Palace, discussing politics and networking at Governor Francis Fauquier’s lavish dinners. Jefferson also attended less formal dances on Duke of Gloucester Street.

He suffered some college heartbreak when his girlfriend, Rebecca Burwell, rejected his awkward marriage proposal. Burwell would go on to wed John Marshall — another College graduate who eventually became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and Jefferson’s political enemy.

Jefferson eventually recovered and went on to graduate, and become a seminal founding father of the United States. Later in life, he deemed his struggling alma mater completely unsalvageable and founded the University of Virginia.

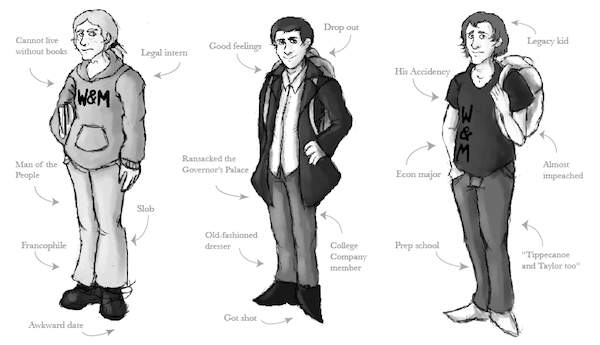

James Monroe

The fifth president of the United States, James Monroe, dropped out of the College of William and Mary in 1775 — only one year after enrolling. The reason wasn’t academic pressure. In grammar school, he had been an excellent Latin and mathematics student, and one of his classmates was later College graduate and Chief Justice John Marshall.

Rather, it was the drums of war that called the young man away from his studies. During this time, the campus was rife with rebellious rhetoric, spread by radical professors like the Reverend James Madison.

College President and notable loyalist Reverend John Camm was even removed from his position as the political situation escalated. The College was swept up in the tide of the American Revolution, quickly forming a College Company, in which Monroe actively participated.

After dropping out, Monroe became an officer and never looked back. As a reaction to the shots fired at Lexington and Concord, Monroe joined an impromptu mob that converged on the Governor’s Palace. Widely despised Gov. Dunmore was absent and not seized in the raid — but his 200 muskets and 300 swords were not so lucky.

Monroe was shot and nearly bled to death during the pivotal Battle of Trenton. He is immortalized as the bearer of the American flag in the painting of Washington crossing the Delaware.

Later in life, Monroe connected with College alumnus Thomas Jefferson and received a legal apprenticeship — he did not care for law itself, only the salary and prestige that it entailed. Monroe went into politics and presided over one of the most successful presidencies of all time — during a period that became known as the “Era of Good Feelings.”

John Tyler

John Tyler graduated from the College of William and Mary in 1807 at age 17 and subsequently lied his way into a legal career — he was too young to take the bar. He studied law with College graduate Edmund Randolph and his own father, Governor of Virginia John Tyler Sr.

Tyler had a difficult, sickly childhood before he enrolled in the College’s preparatory school at age 12, continuing the Tyler legacy at the school. His father, John Tyler Sr., had allegedly been Thomas Jefferson’s roommate in college.

In college, Tyler enjoyed studying economics and did well academically — he found Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” particularly influential. He was fiercely devoted to states’ rights, which alienated many of his fellow Whigs. Nonetheless, he ran on the Whig ticket with his fourth cousin once removed, William Harrison.

After President Harrison passed away shortly into his presidential term, Tyler ascended to the position of chief executive. Because of the nature of his promotion, his political enemies nicknamed Tyler “His Accidency.”

He had a generally unsuccessful presidency, during which his entire cabinet resigned in disgust over his policies.

He was nearly impeached, but found success in securing the annexation of Texas — an act which his successor James K. Polk would finalize. During the Civil War, Tyler sided with the Confederacy shortly before dying.

He is remembered more for Harrison’s campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” than for his rather-obscure and contentious presidency.

Read more about famous TWAMPs and presidential visitors here.